Budo Beat 11: The Essence of Budo

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The following is the very first instalment of my two-year series of articles titled “The Philosophy of Zanshin” published in Japanese in the Nippon Budokan’s monthly magazine, Gekkan Budo. This one came out in January, 2023. It’s a rough translation, but I hope it offers some insight.

The Philosophy of Zanshin Part 1: The Essence of Budo

Introduction

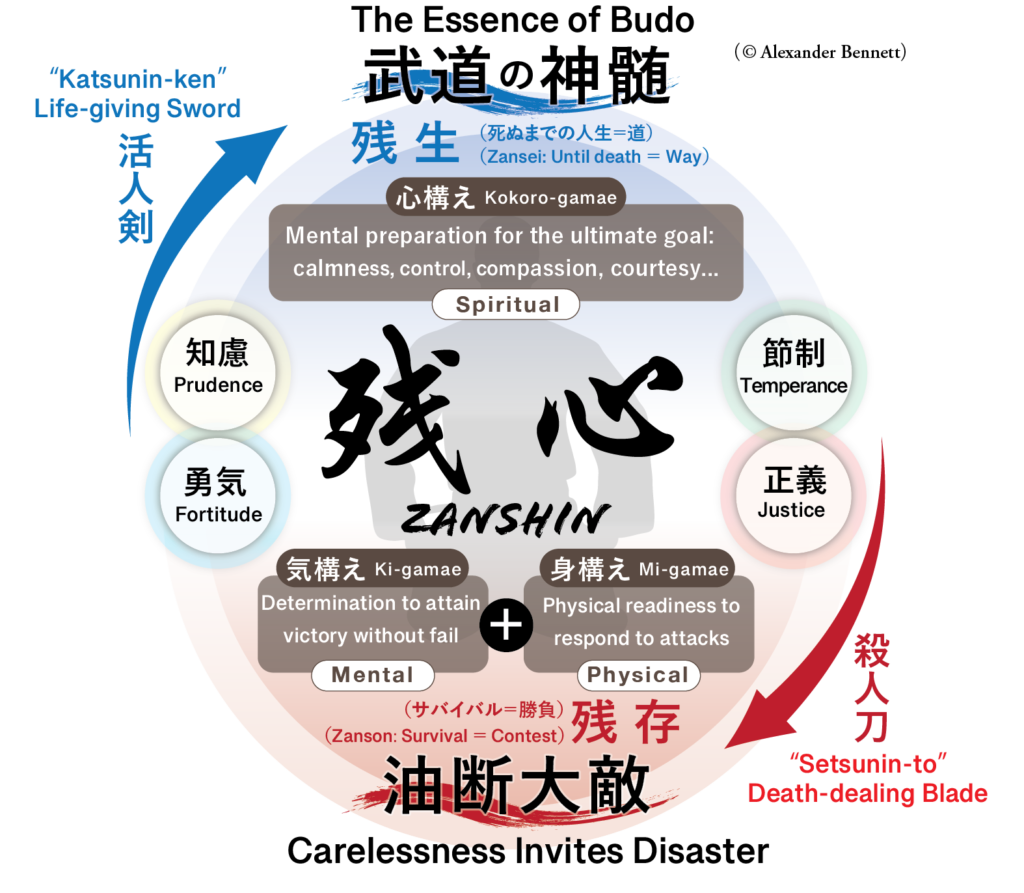

Zanshin—a term deeply rooted in the philosophy of Japanese martial arts—is much more than a technical requirement; it embodies vigilance, composure, and readiness. Defined by the AJKF’s Kendo Japanese-English Dictionary as a state of mental and physical alertness after executing a strike, zanshin is an essential element of kendo. Without it, a strike cannot even be considered valid, emphasising its role as both a technical and philosophical cornerstone.

Kendo aside, zanshin is a part of all the budo disciplines. The teachings of budo extend far beyond physical techniques—they represent a way of life built on discipline, humility, and respect. At its core lies zanshin, a concept that unifies the sharp attentiveness required in the heat of battle with a broader mindfulness that applies to everyday life. In this introductory article, I will explore how zanshin serves as a bridge between martial practice and life philosophy, offering timeless lessons for navigating modern complexities.

Beyond the dojo, zanshin unfolds in two interconnected dimensions: the moment-to-moment vigilance of “micro zanshin” and the expansive awareness of “macro zanshin.” These perspectives reveal zanshin as a principle that transcends martial arts, providing a universal framework for living with clarity and purpose. This is the first of 25 articles examining how the enduring principles of budo resonate in today’s world, shaping our approach to both difficulties and opportunities.

From the composed restraint of Anton Geesink at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics to the quiet dignity demanded of practitioners in the dojo, zanshin embodies the delicate balance between action and stillness, triumph and humility. Throughout this series, I will delve into the essence of zanshin, uncovering its pivotal role in budo and its broader implications for living a life of intention and awareness.

Ideal Budo Conduct

In budo, practitioners are taught to display humility in victory and grace in defeat, embodying the discipline’s core values of respect and composure. In the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Anton Geesink of the Netherlands defeated Kaminaga Akio in the open-weight judo final, earning the gold medal. Despite his victory, Geesink neither revelled in triumph nor jumped for joy. When Dutch supporters, overcome with excitement, stormed the competition area, Geesink, still pinning Kaminaga to the floor, raised his hand. With an almighty glare he stopped them in their tracks before they could invade the hallowed tatami mats to congratulate him.

Afterwards, the two competitors calmly adjusted their judogi, bowed, and concluded the match as perfect gentlemen, demonstrating nothing but mutual respect. There were no victory poses from Geesink, nor were there tears from Kaminaga. (See here)

I always show this scene to students in my classes on budo theory at Kansai University as it perfectly embodies the dignity and composure expected of a budo practitioner. Sadly, such displays of self-control and respect for one’s opponent have become increasingly rare in modern top-level sports, including budo, where the focus often shifts to individual triumphs rather than shared honour.

I am reminded of a moment from the karate competition at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, where karate made its official Olympic debut. In the final match of the men’s over-75 kg kumite division, Tareg Hamedi of Saudi Arabia had a 4-1 lead just one minute into the bout. However, he delivered a kick to the neck of Iran’s Sajjad Ganjzadeh, who immediately collapsed to the floor. Believing he had won the match, Hamedi celebrated with frenzied fist pumps. (See here)

But the outcome took an unexpected turn. Medical staff rushed to Ganjzadeh’s side and carried him out on a stretcher. A few minutes later, the umpires ruled that Hamedi had committed a foul by using a dangerous technique (high kick) and disqualified him. Hamedi, who had been on the verge of securing Saudi Arabia’s first-ever Olympic gold medal, was devastated and burst into in tears of frustration.

Scenes like this are familiar across all sports. Athletes celebrate victory with fist pumps and triumphant poses, while defeat often brings raw disappointment or exasperation. As spectators, we are captivated by these raw, unfiltered emotions—moments that crystallise the culmination of gruelling effort and personal sacrifice. We find ourselves deeply respecting their efforts, not just for their physical achievements but for their human vulnerability. Witnessing these genuine highs and lows creates a profound connection between athlete and audience, offering a shared experience of triumph and struggle. This is the reason why people are drawn to sports: they mirror the drama of life itself, with all its unpredictable twists and emotional stakes. Sharing in the highs and lows that follow a match is like experiencing the drama of life itself.

Academic Research on “Victory Poses”

There is a fascinating study (here) on the phenomenon of the “victory pose” and the celebratory instinct behind it. David Matsumoto, a professor at San Francisco State University and a well-known American judoka, analysed the reactions of winners in Olympic and Paralympic judo competitions. His research revealed that victory poses are exhibited not only by athletes across various cultures but also by visually impaired athletes. Matsumoto found that victory poses signal feelings of triumph, challenging previous studies that labelled the expression as pride. According to him, expressions of triumph act as instant proclamations of success or achievement, while pride emerges from a more reflective process, tied to a sense of self-worth that requires time for evaluation.

The study suggests that the physical impulse to demonstrate dominance after victory stems from an instinctive reaction. Actions such as raising one’s arms above shoulder level, puffing out the chest, tilting the head back, and smiling not only convey joy but also reflect an evolutionary need to establish social order and status. This conclusion highlights the dual function of such gestures as both expressions of emotion and tools for asserting one’s position in a social hierarchy.

While this may be a natural reaction, in the world of budo, such expressions have long been condemned. They are seen as lacking self-control, humility, and consideration for one’s opponent—a betrayal of the deeper meaning of budo as a dō or michi (Way). In my book, The Bushidō Japanese Don’t Know (Bunshun Shinsho, 2013), I provocatively declared on the cover and in the text, “Victory poses have corrupted judo!” Since then, it appears that such displays have gradually diminished among Japan’s elite judo practitioners.

For instance, Olympic gold medallist Ōno Shōhei commented in an article (here) on the comprehensive sports news site THE ANSWER titled, “Why Doesn’t Ōno Shōhei Smile? The Man Aiming for Olympic Victory Discusses ‘Aesthetics of the Tatami.'”

“To be honest, when I first became a champion, I probably did my fair share of victory poses and celebrations. But now, having grown accustomed to the feeling of winning, I don’t get overly emotional about it anymore. (…) In a sport where you win by throwing your opponent, celebrating in front of someone who’s already feeling frustrated might stir up emotions beyond disappointment. That’s why I choose to do nothing. That’s just how I approach it.“

Japanese Virtues

I’d like to believe my book has had a positive impact, though perhaps that’s just wishful thinking on my part. Regardless, this stoic approach to suppressing emotions is celebrated in the article as an “aesthetic” of budo, a perspective deeply connected to the essence of Japan’s traditional culture. In Japan, overt expressions of emotion and self-promotion have long been viewed as undesirable traits.

For example, in his 1894 book, Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, Lafcadio Hearn (Koizumi Yakumo) writes about the “mysterious Oriental smile”:

“And furthermore, it is a rule of life to turn constantly to the outer world a mien of happiness, to convey to others as far as possible a pleasant impression. Even though the heart is breaking, it is a social duty to smile bravely. On the other hand, to look serious or unhappy is rude, because this may cause anxiety or pain to those who love us; it is likewise foolish, since it may excite unkindly curiosity on the part of those who love us not.”[1]

This observation underscores the cultural importance of considering others’ feelings and prioritising harmony for which Japan is well known for, even at the expense of personal emotions. It reflects a time when maintaining a sense of social balance and avoiding any disruption to collective peace were seen not merely as virtues but as essential elements of daily life in Japan.

In budo, too, controlling one’s emotions is crucial, as it reflects both discipline and respect. If there is to be any reaction or expression, it should align with the traditional teaching: “Reflect when you strike successfully, and be grateful when struck” (Utte hansei, utarete kansha). This teaching embodies the humility and self-awareness expected of practitioners. In other words, if anything one should “frown” when victorious, as a reminder of the struggle and respect for the opponent’s effort, and “smile” when defeated, as an acknowledgment of the lessons learned and the opportunity to grow stronger. This mindset reinforces the crux of budo as not just a physical practice but a lifelong journey of character development.

Article 3 of the “Budo Charter“, established by the Japanese Budo Association in 1987, similarly emphasises this attitude: “Whether competing in a match or doing set forms (kata), exponents must externalise the spirit underlying budo. They must do their best at all times, winning with modesty, accepting defeat gracefully, and constantly exhibiting self-control.”

A budo practitioner who expresses joy in victory might be likened to a football player doing an elaborate goal celebration or a sprinter blowing kisses to the crowd after crossing the finish line. Such exuberance, while perfectly at home in those arenas, strikes a jarring note in the world of budo. This is not to disparage the celebratory instincts of athletes in other sports—a well-executed goal or a hard-fought victory certainly deserves its moment in the spotlight. However, budo demands a different ethos. Rooted in the discipline of combat and the reverence for one’s opponent, its traditions view self-centred displays of triumph as more than just poor form—they undermine the deeper purpose of the art. To celebrate ostentatiously is, in essence, to twist the blade in an opponent’s wounds, violating the respect and humility that lie at the heart of budo.

As has become widely reported, in kendo matches, a victory pose by the winner can result in the revocation of the point they just earned. Such behaviour is seen as disrespectful to the opponent, reflecting a lack of composure and moral discipline. This is because kendo emphasizes the principle of zanshin—a state of continued awareness and readiness, even after a decisive moment. A celebratory gesture disrupts this ideal, signalling not only a lapse in focus but also a disregard for the mutual respect that underpins the art of kendo.

What is Zanshin?

This brings us to the main topic: What exactly is zanshin? At its core, zanshin is the state of remaining alert and prepared for an opponent’s counter-attack, even when one’s own attack has not achieved its intended effect. It is a practical mindset, essential for self-defence and survival in the context of true combat.

Namely, zanshin is a distinctive concept within budo, born from a world shaped by life-and-death struggles. True zanshin is neither a forced effort nor a superficial gesture. It is the seamless continuation of physical and mental vigilance that naturally arises after a wholehearted attack, embodying a perfect unity of mind, body, and spirit. Takano Sasaburō, a trailblazer in modern kendo and budo philosophy, articulated zanshin as follows:

“When you strike with your full spirit, leaving nothing in reserve, it generates a sense of renewal. By committing entirely to the strike and allowing the struck blade to naturally fall away, a vigilant mind—fully attuned to the opponent—will naturally persist. However, if you strike with the deliberate intention of maintaining focus, your mind will become fixed in that moment, creating an opening for your opponent.” (Kendō, 1914)

My interest in the concept of zanshin lies in its “mindset”—the broader, macro-level perspective that often goes undefined. While “mindset” (kokoro-gamae) and “mental readiness” (ki-gamae) are frequently used interchangeably, I believe drawing a distinction between them is essential to fully grasp the profound depth of zanshin. “Mindset” refers to an enduring state of mental and emotional balance, a foundational outlook that informs all actions and decisions. On the other hand, “mental readiness” describes a more immediate, situational awareness and preparedness to respond in the moment. By distinguishing these terms, we can better appreciate how zanshin bridges both the overarching philosophy of presence and the practical application of vigilance.

If expressing victory poses is a natural emotional response embedded in our DNA, why is it considered problematic in budo? The answer can be approached from several perspectives in the context of budo and zanshin:

Moral Perspective Budo matches are fundamentally based on life-and-death struggles, where the victor survives, and the defeated perishes. Taking a life, even in self-defence, is a tragedy and not something to be celebrated.

Practical Perspective In a real combat scenario, revelling in the joy of victory increases the risk of being counter-attacked.

Educational Perspective Precisely because the emphasis on victory is hardwired into us, significant training is required to suppress such excitement. This provides an opportunity to refine character and cultivate virtues, such as:

• Prudence (Discernment and Wisdom) – The ability to discern appropriate actions at the right moment in a given situation.

• Fortitude – The strength to confront fear, anxiety, and intimidation.

• Temperance – The capacity for self-control, restraint, and moderation.

• Justice – The power to act fairly and uphold what is right.

By addressing these aspects, zanshin transcends its technical application and becomes a vehicle for cultivating moral and spiritual growth, embodying the essence of budo.

Ascetic Perspective Celebrating victory reflects an immature level of development as a practitioner. To maintain a mindset of continuous improvement, it is essential to evaluate one’s performance objectively, honestly, and humbly. Zanshin is a critical element of training, as it represents the effort to suppress ego rather than adorn it. Such behaviour runs counter to the budo philosophy of the dō—the Way of striving to negate the ego.

Traditional Perspective How many kata in classical martial arts (koryu bujutsu) end with a victory pose? I have never seen any. Each concludes with solemn bowing, expressing gratitude to the opponent, and reflecting strictly on oneself. This represents the fundamental attitude of budo and is one of the unique characteristics not demanded in most other competitive sports (at least, nowadays).

Aesthetic Perspective Victory poses lack dignity and composure, falling short of the refinement and grace that budo practitioners are expected to embody.

Zanshin as a Tool for All Aspects of Life

Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481) was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk, poet, and iconoclast known for his eccentric personality, sharp wit, and unorthodox approach to Zen practice. He rejected the rigid formalities and hierarchical structures of traditional Zen institutions, instead advocating for a more direct and personal connection to enlightenment. Ikkyū’s teachings and poetry often emphasized the transient nature of life, the value of simplicity, and the importance of emotional authenticity. He once wrote the following poem which says “zanshin” to me:

“When the fire in your chest begins to blaze,

Hold back the waters of your heart to quell its flames.”

The mindset of zanshin can be likened to the “waters of your heart”, a steady force that cools the flames of impulsive emotions, maintaining composure and balance even in the most turbulent circumstances. Embracing zanshin in a broader, more holistic sense transforms it into a profound framework for navigating the challenges and uncertainties of life with clarity and grace.

For example, taking care of one’s health and well-being can be considered a form of zanshin. Eating thoughtfully, resting adequately, and maintaining a balanced lifestyle reflect an awareness that one’s body and mind are interconnected and require care. Showing compassion towards friends and others is another way zanshin manifests. Whether it’s taking the time to truly listen to someone’s concerns or offering help when it’s inconvenient, such acts of awareness foster deeper connections. In the workplace, practising zanshin might mean stepping back from the chaos to prioritise tasks, reduce overtime, and avoid careless mistakes—a kind of vigilance that not only ensures better outcomes but also minimises burnout. Even something as simple as pausing to let another driver merge in traffic embodies zanshin, extending the practice of awareness to the rhythms of daily life. The true value of zanshin is realised when it extends beyond the dojo or arena into everyday life.

Many failures can often be traced back to a lack of zanshin. It is not simply about losing focus but about neglecting the ethical awareness that demands we take full responsibility for our actions and our destiny. Zanshin acts as both a compass and a mirror—guiding us toward self-improvement while reflecting our shortcomings. It reminds us that growth is not a passive process; it is the conscious, deliberate effort to refine ourselves, to become more aware, more considerate, and ultimately, better human beings.

Moreover, zanshin serves as the foundation for the ability and courage to accept and adapt to change in any situation. It cultivates an awareness that challenges whether what has been done so far is truly just and correct, encouraging a mindset of questioning the status quo. In an era of constant change and upheaval, I believe zanshin holds the key to preserving and enriching the future of budo culture.

The number of people practising budo has seen a sharp decline in Japan, and few would argue against the notion that budo culture is now at a crossroads. In an era dominated by digital interactions and virtual realities, the true strength of budo lies in its face-to-face, analogue essence—a quality that preserves what is profoundly human. Budo embodies fundamental principles of life, such as discipline, respect, and genuine connection, which are becoming increasingly scarce in modern society. To ensure its survival, it is imperative to find meaningful ways to instil the budo mindset in the next generation, helping them rediscover the value of authentic human interactions through its timeless teachings.

The philosophy of zanshin in budo represents a traditional way of thinking and culture that must be passed down through generations. It is not a relic of the past but a timeless wisdom that continues to hold profound relevance for human interaction and personal growth.

“Even if you snap a blooming branch of mountain cherry blossoms,

Let not your heart grow slack,

For the mischievous spring wind may yet scatter its petals.”

As expressed in this poem, one might admire the blossoms held in one’s grasp, only to have a mischievous breeze scatter them away. This serves as a metaphor for the delicate preservation of budo’s values, which could similarly be swept away if neglected.

With this in mind, I aim to explore how we can ensure that the values of budo are preserved and not scattered like petals in the wind. Using “macro zanshin” as a guiding concept and the “Budo Charter” as a foundational framework, this series will delve into budo from multiple perspectives. I will examine its role in human development, the nature of training and competition, the challenges and opportunities for its future, and its potential for global dissemination.

In the end, the spirit of budo—rooted in zanshin—offers more than a roadmap for combat or winning matches; it provides a way of navigating the unpredictable chaos of life. By preserving its timeless lessons and adapting them to modern challenges, we stand to gain something profound: the ability to move through the world with purpose, humility, and unshakable awareness. If the petals of tradition are not to scatter, we must cherish the tree from which they bloom.

In the next instalment, I will delve into the history of the concept of zanshin and the earliest references to the term.

[1] Lafcadio Hearn, Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1976), p. 668

No comments yet.