Budo Beat 32: Getting a Grip

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

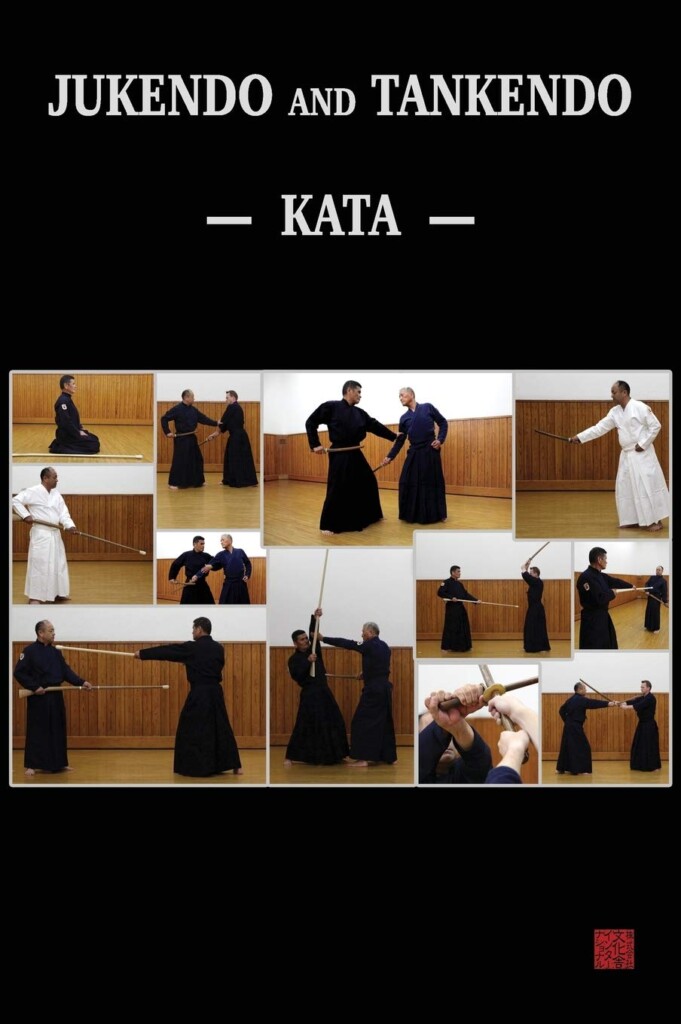

I’m writing this from Fukushima Prefecture, where the 6th International Jukendo and Tankendo Seminar is in full swing. Between the one-handed tanken and the two-handed mokuju, I’ve been reminded, sometimes rather forcefully, that one of the hardest things to grasp in budo is te-no-uchi. Yup, “hard to grasp” is a painful pun, but so is my chest and shoulder after a few days of being stabbed by people confusing enthusiasm with efficiency. The extra, unnecessary power when executing techniques makes them clumsy and painful rather than crisp and controlled. I’m probably just as guilty myself at times, so I’ll keep those stones in my pocket for this particular glasshouse.

For the uninitiated, te-no-uchi is the way you grip and release a weapon in budo so that power, precision, and control all come together. It is not just “holding on” but a dynamic use of the fingers, palms, and wrists to channel energy into the strike at the exact right moment, then immediately relax to let that energy flow through the target.

But, te-no-uchi is not simply “grip” in the sense of holding a shopping bag. It is the precise and deliberate way the hands hold, release, and work with the weapon, turning it from an inert object into something that moves exactly as you intend. Of course, it’s a concept that goes far beyond jukendo and tankendo. In any martial art, knowing what your hands are really doing is the difference between graceful skill and literally bludgeoning your way through.

There is an old budo poem that goes as thus:

“When the te-no-uchi is true, the sword moves as the heart intends.”[1]

In kendo, naginata, jukendo and the other weapon arts that I do, it is often glossed as “grip”, but that is kind of like describing a Stradivarius as “a box with strings”. The characters (手の内) can mean “inside the hand”, “palm”, or “inner working of the hand”. In practice, it refers to how you hold, guide, and release the weapon, from the precise placement of your fingers to the timing of your muscles’ tension and relaxation. It is not just about holding on. It is about knowing how to let go without letting go…

As Miyamoto Musashi puts it, “In both sword and hand there is life and death.” In other words, the hand that freezes forgets to cut and dies; the hand that is steady and ready at all times lives. In a standard kendo grip, for example, the right hand sits just under the guard, the left hand near the butt of the handle, wrists naturally turned inward so the thumbs point slightly forward and down. The left hand is the engine. Old-timers will tell you that sword usage is essentially “left-handed”, while the right hand is the polite assistant, not the overbearing uncle who takes over at the family barbecue!

Metaphors about te-no-uchi shared in the dojo often have a homely charm, helping beginners connect a strange new skill to familiar sensations. Imagine cradling an egg, I was once taught: squeeze too hard and you’re making omelette; too softly and you’re making scrambled eggs. It’s this balance that the following old poem points to:

“To merely hold and to strike are worlds apart / Observe well the miko’s hands as she rings the sacred bells.”[2]

The poet here is likening proper grip and control (in martial arts or any refined skill) to the delicate, precise way a shrine maiden shakes her suzu bells in ritual, rather than just “holding” them. It is alluding to a vital skill in budo. A living grip (whether on a weapon or directly on the opponent) adapts, never fixed, never slack, able to meet, parry, and strike without stiffness.

This is true for all budo. In kyudo, grip the bow’s handle like a claw and you twist the shot; fail to engage the right pressure points and the arrow floats away like a drunk pigeon. In judo, the kumi-kata is the first battle. Strangle the sleeve or lapel and you lose the sensitivity to feel your opponent’s movement. Go too slack and you’ll probably be on your back before you know it. The best judo grip is unyielding where it must be, alive and fluid everywhere else. In naginata, with its long shaft, over-grip and the tip wobbles like a fishing rod; under-grip and your strike is flippy-floppy flimsy and indecisive. With jukendo and tankendo, incorrect te-no-uchi (too light, or too rigid) leads to dropping your weapon, or perhaps dropping your partner though breaking their ribs!

When you’re struck by someone with correct te-no-uchi, Instead of a jarring pain shooting through your skull, wrists, or torso, there is a clean, crisp impact that makes a beautiful resonating sound, almost like a perfectly hit note on a drum. The sensation is not one of being bludgeoned, but of something being executed so precisely that the sting never arrives (much).

This is where sae (冴え) comes in. It’s a word that means clarity, sharpness, or brilliance. In kendo and other weapon arts, sae is literally and figuratively the cutting edge of skill, the moment where form, timing, and te-no-uchi meet in a strike that rings with purity. It is the difference between a dull thud and a pinging sound that seems to hang in the air for a moment, telling everyone present that they have just witnessed something exact and alive. The following poem sums it up pretty well, I think.

“Though only struck by a bamboo sword without a blade, my breath was cut clean away.”[3]

So, the lesson is that te-no-uchi needs four qualities: strong, weak, fast, light. These are not contradictions; they are partners in a sort of concentrated, shifting dance. Strong when cutting, weak when releasing after the point of impact. Fast to seize an opening, light to avoid telegraphing your move.

Old schools loved their metaphors. One likens it to wringing a wet towel, both hands working together in opposite twists, elbows extending, wrists firm but not locked. Another compares it to holding a paper umbrella in a gale, fingers tightening against sudden gusts without crushing the frame. The Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu which I study teaches that “The heart of te-no-uchi is neither strong nor weak, but in finding the middle.”

The old scrolls of my school also warn about the “diseases” of te-no-uchi: the “stuck hand” that grips so hard it cannot release in time; the “cramped hand” with no slack to absorb impact; the “extended hand” that overreaches and collapses. They describe te-no-uchi for striking, for receiving, and for thrusting, each with its own balance of firmness and relaxation.

The trouble is, te-no-uchi is really hard to teach directly. A sensei can correct your form, but the fine balance of tension and release arrives only through repetition and awareness. One day your hands do something that feels right, and the feedback tells you it worked.

Think of te-no-uchi as the sweet spot between strangling something and letting it slip away. If you’ve ever tried to pour tea from a delicate porcelain pot, you’ll know that grip matters. Squeeze it like you’re afraid it will run away, and you’ll jerk the spout, spill the tea, maybe even snap the handle. Hold it too loosely, and the pot wobbles, the lid rattles, and you risk splashing everyone. The same applies when you beat a drum. Too much force and you punch right through the skin, leaving only an awkward silence and a repair bill. But, too little, and the audience hears more of you breathing than the drum itself.

In te-no-uchi, your arms, hands, palms, and wrists are like an orchestra section, each doing its part in perfect coordination. Your arms set the arc of movement, your hands shape the connection, your palms transmit the energy, and your wrists provide the snap and release. Imagine throwing a stone into a pond: the aim isn’t simply to hit the water, but to send it skimming smoothly across the surface, each bounce carrying its energy forward. A good te-no-uchi strike works the same way: it lands with crispness that “rings” through the opponent’s body and spirit, and then instantly relaxes so that energy continues to flow, not stall. In short, it’s not about raw impact, it’s about delivering a strike whose sound, feel, and intent travel cleanly beyond the moment of contact.

I think good te-no-uchi is very much like throwing the perfect spiralling rugby or gridiron ball. If you just hurl it with brute force, it wobbles through the air losing speed and accuracy. If you lob it without commitment, it flutters short and lands in the grass. When you get the grip, wrist flick, and follow-through just right, the ball spins in a tight spiral, cuts through the air, and drops exactly where you intended. No wasted motion, no wasted energy, just clean, beautiful, efficient delivery.

The same principle is at work in other skills. Casting a fishing line with too much muscle makes the lure smack the water and scare the fish. Too little and it plops a few feet from shore. Playing a guitar chord with too much force chokes the sound. Too little and you get the dreaded buzz. Even opening a jar works this way. Wrenching it with all your strength can make your grip slip, but steady, balanced pressure does the trick.

So, like most things in budo, the concept kind of works outside the dojo. In conversation, it is knowing when to press and when to relax your hold. In negotiation, it is tightening at the right moment and loosening before you cause a break. Actually, in Japanese, te-no-uchi is used in daily parlance to mean more than just the precise way you grip and release a weapon in budo. It can also describe the art of reading another person’s intentions or concealing your own, much like a shrewd negotiator or a poker player keeping their hand hidden until the decisive moment. In another sense, it refers to something firmly under your control, as when a long-sought prize, a hard-won victory, or even an entire realm is said to be “in the palm of your hand.” It can also simply mean the palm itself, evoking what we physically and metaphorically hold.

In any case, the core idea remains the same across all these uses. What you possess, how you handle it, and how much you choose to reveal. In budo, good te-no-uchi is a hallmark of proficiency, showing that your techniques have become second nature. The longer you spend in budo, the more you see it is not only about the hand. The heart, the mind, the breath all need that same alive, adaptable quality. In every budo, te-no-uchi is the thing that makes the technique yours. And when it’s right, i.e., when strong, weak, fast, and light meet in balance, it makes it truly gripping. Sorry…

[1] 「手の内の出来たる人の取る太刀は 心にかなふはたらきをな」 (Te-no-uchi no dekitaru hito no toru tachi wa / kokoro ni kanau hataraki o na) in Kinoshita Jutoku, Kenpō Shigoku Shōden (Budō Shōreikai, 1913) p. 72

[2] 「只持つとうつとは握り違ふなり よく見よ神子の鈴の手元を」 (Tada motsu to utsu to wa nigiri chigau nari / yoku miyo miko no suzu no temoto wo) Ibid., p. 69

[3] 「いといたく打たれて息は切れにけり 刃もなき竹のしなひ乍らに」(Ito itaku utarete iki wa kirenikeri / ya mo naki take no shinai nagara ni) in Abe Mamoru, Kaden Kendō no Gokui (Tsuchiya Shoten, 1965) p. 55

No comments yet.