Budo Beat 42: Kakugo

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

“I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it.” (Nelson Mandela)

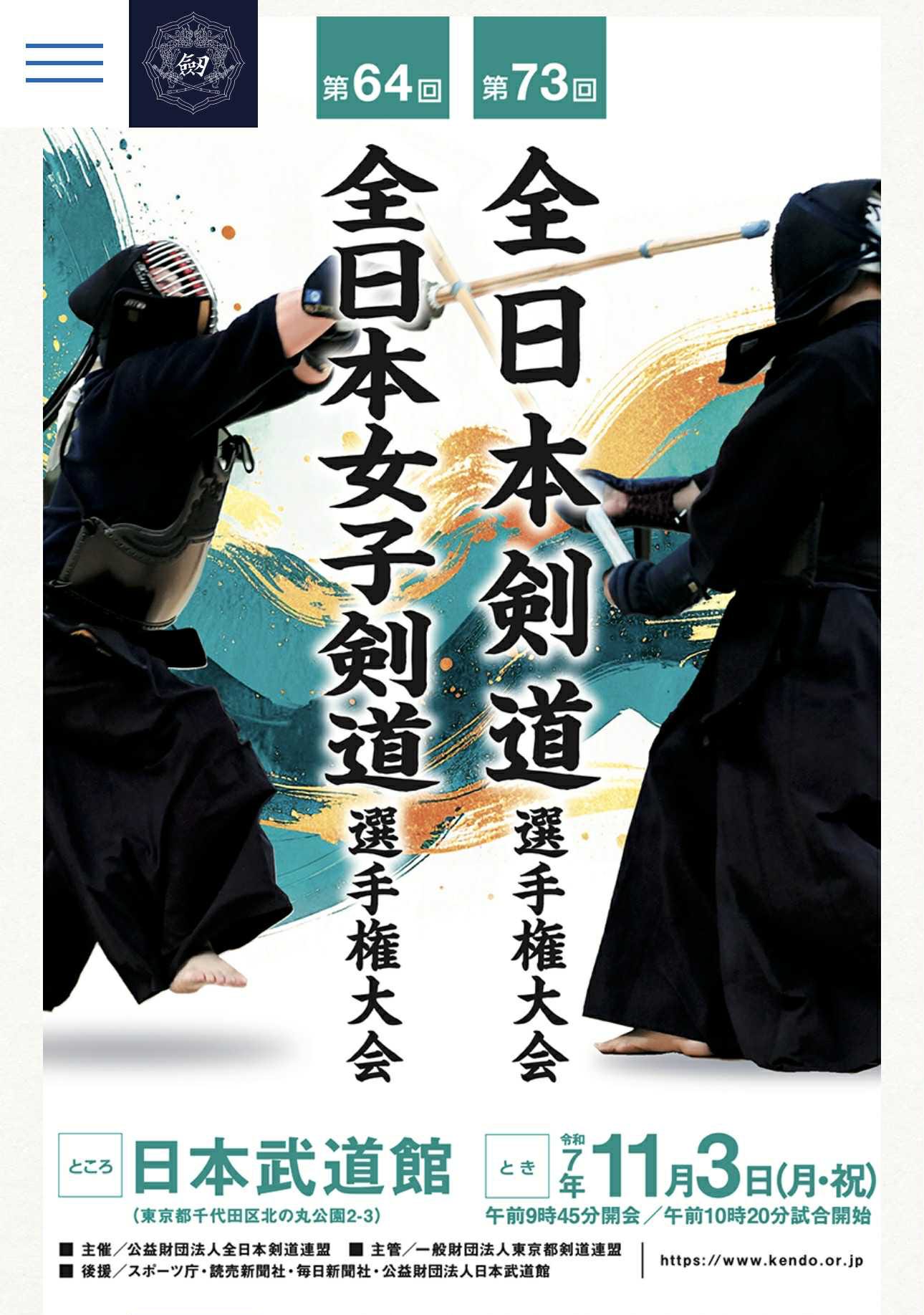

Monday (Nov. 3) marked the 73rd Men’s All‑Japan Kendo Championship, held alongside the 64th Women’s event. (Kendo World videos of the men’s and women’s finals are pasted at the bottom of this blog post.) It always begins the same way, like a well‑rehearsed ritual. Around nine, the crowd trickles in, murmuring as the Nippon Budokan wakes up with that peculiar hum of anticipation and respect. Around 9:45, ten thousand heads tilt upward toward the Hinomaru suspended high in the rafters. The anthem rises, the bow follows, and then the great taiko roars through the hall like thunder, announcing that the day of reckoning has begun.

The Budokan has its own pulse. The air hums like it’s still echoing with the ghosts of every shiai fought here. Conversations are hushed, respectful, as if people know they’re in a temple. Cameras (well, smartphones actually) snap like insects. Competitors circle the green‑sheeted perimeter, loosening shoulders, testing footwork, pretending not to look nervous. Then the first match begins, and the whole hall exhales in unison before being drowned out by the kiai of the first eight fighters, sharp and alive, carving through the air like battle cries from another age.

Just before the first “Hajime”, everything tightens into a single breath. A whole life in budo, the early mornings, the blisters, the keiko that left you questioning your very sanity… All of it shrinks into that heartbeat before movement. In that suspended instant, the world goes quiet, and the air tastes like iron and sweat. Then the command comes, and instinct takes over. Cut, respond, adjust, survive. Fate doesn’t shout or boast; it just stands there at the far end of the court, waiting to see what you’ll do.

Last year when I wrote about the championships, my theme was bu’un (武運), “martial fortune”. It carries a certain old-school dignity, the sense that luck still has a role to play no matter how strong or prepared you are. You can train for decades, sharpen your waza until it slices through thought itself, and yet the budo gods might still turn their backs. Bu’un favours some and abandons others. It’s what makes budoka human.

But this year, sitting in the same grand arena and watching another generation of kenshi fight their hearts out, I found myself drawn to something beyond luck. In budo, bu’un hints at the random side of things. Those invisible factors that decide whether your strike lands clean or glances off by a hair’s width. And kakugo (覚悟), resolve, is what bridges that gap. You can’t control fate, but you can decide how you meet it. That, to me, is the heart of budo.

The early rounds at the All‑Japan Championships are merciless. Big names vanish before you’ve even finished your can of hot coffee. One blink, one late men, a flag that hesitates, and that’s it. The atmosphere squeezes every breath out of you because everyone here can already do kendo. They wouldn’t be on this floor otherwise. Now it’s about who can stay honest when the world shrinks to the space between two shinai. Who can stare their own nerves in the face and still step in.

These thoughts came to me after bumping into one of the competitors, a former student at my university. I won’t say which prefecture he was representing, but it wasn’t his first rodeo. The first thing out of his mouth was, “I’m so bloody nervous.” All I could muster was, “Just do what you always do, mate. You belong here. Believe in yourself and enjoy the ride. I can feel something good afoot brother.” It was the best I had at the time, and the moment it left my gob I knew it sounded painfully clichéd. I wished I’d said something wiser, something that cut closer to what I really meant; that if he could just meet whatever was coming with a calm heart instead of wrestling with what-ifs, he’d be fine. You can’t outthink fate, but you can meet it with resolve.

It’s easy to see fate as some mystical or unfair hand that deals out wins and losses, but in budo it’s usually stripped bare. Fate is the moment when all your careful training still isn’t enough. It’s the opponent whose rhythm neutralises your best technique, or the referee’s call that reminds you this isn’t a world you can control. In that sense, fate isn’t cosmic at all. It’s simply life, unpredictable and indifferent. What matters isn’t the roll of the dice but the resolve you bring when it lands against you.

Behind that calm acceptance is something deeper. The best kenshi don’t waste energy resisting fate, they meet it head on. Every opponent, every exchange, becomes part of the same ongoing dialogue with life itself. You win, you lose, you bow, you move on. That rhythm is what makes the All‑Japan Championships beautiful. Everyone out there, from the first‑round dropout to the eventual champion, understands it without needing to say a word.

Kakugo is a strange thing. It’s not the same as confidence, and it’s not the same as optimism. It’s more like the silent agreement you make with yourself when you stop expecting the world to be fair. You train, you fight, you bow. You might win, you might not. But you do it anyway, without bitterness. In that acceptance lies real freedom.

The word kakugo literally means to be prepared, but in budo it’s more like being ready for anything. Not ready as in expecting victory, but ready as in accepting whatever comes. There’s a line in one of Musashi’s writings that goes along the lines of, “Think lightly of yourself and deeply of the world.” That’s kakugo in a nutshell. The less you cling to your own success or failure, the clearer you see what’s in front of you.

I watched my former college student step up for his first round. Like most of the opening matches, you could feel the tension before the referee even said Hajime. He pressed forward, applying steady pressure, but the tightness in his shoulders betrayed him. The nerves were slowing his strikes, holding him back from what he was capable of. In truth, almost every first-round match looks like this. Nobody wants to lose straight out of the gate. It’s ironic, really. The harder you cling to the idea of not losing, the more you stop yourself from truly fighting. But it’s also human. We’ve all been there, trapped between hesitation and resolve, trying to remember that kendo only comes alive once you let go.

That tension in the first round is part of the process. Every competitor has to face it. Some never quite shake it, carrying that tightness through every exchange. Others, after years of living in that space between fear and action, finally learn to release it. That’s when kakugo begins to take shape. The moment when anxiety gives way to acceptance, and acceptance turns into freedom.

By the middle rounds, the whole atmosphere changes. The early panic burns off and settles into something taut and deliberate. Each movement is measured. Every breath counts. Across all four courts, players stand frozen for what feels like eternity, waiting for the other to move first. To an outsider, it might look like nothing is happening, but inside that stillness there’s a storm. Timing, instinct, doubt, and fear collide in silence. This is the true heart of kendo: a dialogue between fate and resolve. Who will take the risk? Who can hold their nerve a heartbeat longer? Who trusts themselves enough to step in when the moment opens?

There’s a kind of beauty in watching someone lose with grace. The fellow I’m referring ended up losing in the second round. After a hard-fought match, his opponent landed what was judged to be men and that was that. He froze for a moment, then I thought I saw a faint grin flicker across his face. It wasn’t the stiff smile of politeness, but a subtle one of acceptance. He bowed, gathered his gear, and walked off the court. There was something quietly noble in that moment. He had faced what came his way and met the result with dignity. That’s kakugo in its purest form.

I have heard it explained that at a certain level, kakugo leads naturally into mushin, the state of no‑mind. Once you’ve accepted everything that can happen, fear loses its grip and the body begins to move of its own accord. You stop hesitating. You stop analysing. You simply respond. This isn’t passivity. It’s the deepest form of readiness. The mind and body become one, unhindered by judgment or ego. The paradox of budo is that the more you surrender to what might happen, the more freedom and precision you gain. You start to see clearly because you’ve stopped trying to control the outcome.

In the Budokan today, there were flashes of that. You could tell when a competitor had let go of the outcome and entered that flow where every movement made sense. It wasn’t always the champion who reached it. Sometimes it was a player who lost in the quarterfinals, but in those exchanges, they embodied the ideal of budo more perfectly than any trophy could measure.

When the final match ends and the winner’s name echoes over the PA system, the applause feels warm but tired. The champion bows, the speeches roll on, and the buzz of the day slowly fades. Sitting there watching people pack up their gear, I’m reminded that winning matters, and the champions deserve every bit of it. But kakugo isn’t only found on the top podium. It’s there in every competitor who steps onto the Budokan floor, faces uncertainty, and gives everything they have. You can see it in the way they fight, and in how they bow when it’s over. Kakugo runs through the whole thing, from the first Hajime to the final bow, not just in the moment after it ends.

In life, as in budo, you don’t get to choose what comes at you. Accidents, lucky breaks, defeats, and small miracles all turn up whether you’re ready or not. What matters is how you stand when they arrive. You can flinch and complain, or you can meet them with the steady calm that comes from years of falling down and getting back up—the kind of calm that says, “Whatever comes, I’ll deal with it.”

Of course, there’s an old kendo poem that sums it up nicely:

Resolve yourself to be struck when you step in for men.

Even if you’re struck, go.

Even if you’re struck, go.[1]

That’s really what it comes down to. You train to beat the odds, but what you actually learn is how to face them. You fight to win, but you end up realising that true strength also lies in how you lose. Fate takes you to the edge. Resolve is what helps you step forward with your head up, come what may.

[1] 伸び面は打たるるものと覚悟して 打たれても行け 打たれても行け (Nobi-men wa utaruru mono to kakugo shite, utaretemo yuke, utaretemo yuke) in Abe Mamoru, Kaden Kendō no Gokui (Tsuchiya Shoten, 1965), p. 75.

No comments yet.