Budo Beat 28: Finding Your Inner Goose

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

Kiai is a powerful shout used in martial arts to focus energy, boost confidence, and intimidate opponents. It’s like letting out a fierce yell right as you strike or defend, helping you commit fully to the action. The kill cacophony!

Recently, at training, I got called out for being too “enthusiastic” with my kiai. Apparently, my excessive zeal was giving opponents no chance to approach (which means I can’t lure them in) and left my own movements stiff and predictable. Besides, I was yelling so hard I almost passed out. I never would’ve lived that down!

Still, this criticism came as a surprise, given how often we’re usually urged to shout like we mean it, the louder the better. But it turns out kiai isn’t about volume, and my manic gusto made me sound less like a seasoned budoka and more like a bullhorn on legs. I was told I needed to graduate from this mentality to go the next step. It should be a natural progression.

Kiai (気合), central to Japanese martial arts, originally didn’t mean shouting at all. In early usage, it referred to harmony or synchronisation between people, extending later to mood or atmosphere. In modern Japan, the phrase ki ga au (気が合う) describes people who naturally click with each other or share good chemistry. It’s often used to talk about friendships or relationships where personalities match effortlessly, making interactions comfortable and enjoyable.

Also, another similar term is aiki. Same kanji, different order, but what is the difference? Kiai (気合) is basically an overt shout projecting energy outward, boosting power and intimidating opponents. In contrast, aiki (合気) subtly blends one’s energy with an opponent’s, harmoniously redirecting their force without direct conflict. Both involve managing 気 (ki), but 気合 emphasizes external projection, while 合気 prioritizes internal harmonization.

Anyway, in the context of martial arts, budo practitioners understand kiai as the projection of energy and intent through a sharp, focused shout. But this isn’t about making noise for the sake of it. Real kiai marks a state of intense clarity, concentration, and decisiveness. But, there’s certainly nothing decisive about how it has been traditionally taught.

“Kiai is to grasp the wind—

stand still,

and listen carefully with your nose.”[1]

What?! Is this some cunning plan to murder comprehension entirely? Even the old masters knew explaining kiai was about as straightforward as nailing jelly to a wall. Takano Sasaburō, in his classic Kendō, confessed it was “tricky to pin down.” He urged practitioners to “feel it firsthand…” Gee, thanks sensei. Salute the budo gods, however, for some dummy-friendly poems:

“Do not ask others what kiai is. Instead, seek it in the waking and sleeping, in the crying and laughter of a newborn child.”[2]

In other words, true kiai is intuitive, spontaneous, and pure; qualities embodied naturally by infants but tough for adults trained to overthink everything. Notwithstanding, allow me to plant the seeds for more overthinking. Kiai encompasses two modes: static (sei) and dynamic (dō). Static kiai means absolute mental and physical readiness without visible effort—no slackness allowed. The second your opponent falters, you shift gears and attack decisively. In that instant, static becomes dynamic. Both states require full mental engagement and unwavering resolve, so shouting without intention or wild physicality won’t cut it.

Simply put, genuine kiai isn’t about lung power, it’s about gut power; it’s mental warfare, spirit against spirit. You can’t fake it with volume. You get there through rigorous physical training and, more importantly, relentless mental discipline.

There are a few [tall?] stories from the age of yore that come to mind about the dizzying heights of utterly seraphic kiai. General Li Guang was a renowned Chinese military leader during the Han Dynasty, famed for his extraordinary skills in archery. According to legend, he once mistook a distant stone for a tiger and shot an arrow at it with complete determination. Remarkably, his focused intent (kiai) was so powerful that the arrow reportedly penetrated deep into the solid rock, illustrating how unwavering belief and kiai can transcend physical limitations. I’m not sure if he shouted when he shot, the but the next guy was definitely a screamer. Mikogami Tenzen was a renowned Japanese swordsman. One famous tale describes how he demonstrated his turbocharged kiai by shouting and literally shattering an earthenware jar without touching it. This story implies how intense mental concentration and internal energy, when fully unified, can produce seemingly supernatural physical effects.

Now, back to that “natural progression” thing. Once you’re proficient in technique and matured spiritually, internalising your courage becomes critical. Rather than shouting it out, you quietly accumulate power. This advanced stage, known as “silent (musei) kiai”, eliminating needless noise and turning you into an intimidatingly calm presence. It won’t smash earthenware jars, but your opponent will wilt under the pressure. As the budoka gets older, it seems that kiai gets quieter, but more potent at the same time. That’s because it’s not the voice that matters as much as the voice behind the voice.

Which reminds me of a related concept: kakegoe (掛け声) in budo is a short vocal shout or call used during martial arts training or matches. Slightly different from kiai, which is typically a powerful, spirit-focused projection intended to intimidate or disrupt an opponent, kakegoe serves more as a rhythmic shout or cue. According to the AJKF’s dictionary of kendo terms, the two concepts are described in the following way:

Kake-goe (n.) A natural vocalisation which shows that one is full of spirit and prepared mentally and physically.

Kiai (n.) The act of concentrating on the opponent’s moves and on one’s planned moves and mounting a challenge with extreme caution. Also, it refers to the vocalisations one produces when in such a state of mind.

So, there are differences in nuance, but the terms are, rightly or wrongly, often used interchangeably. The easiest way to make a distinction is that kakegoe are always vocal. Kiai can be expressed both vocally and silently. In many way’s kakegoe represents a kind of verbal communication; a greeting that demands a response. Traditional forms in swordsmanship, for example, often use three distinct kakekgoe shouts: “Yā” signals readiness; “Ei” accompanies decisive attack; “Tō” marks defence or counters. These remain central in kata practice, while in modern kendo matches practitioners typically “greet” each other first with an almighty yell, then shout the targeted area, like “men” or “kote” as they strike. (Not beforehand, because that would kind of give the game away!) That’s why kendo is usually a lot louder and “vociferous” than other budo disciplines. Having said that, some of the colourful “sports karate” that assaults my eyeballs on my Facebook feed these days has taken raucous howling to a truly ear-splitting new level.

We’re taught that a proper kiai must be pure, strong, sharp, and resonate from deep in the gut—quite literally, your tanden. Beginners often struggle with this. Apart from just the embarrassment of yelping at another person, they typically resorting to shouting from the throat, which achieves little beyond temporary hoarseness.

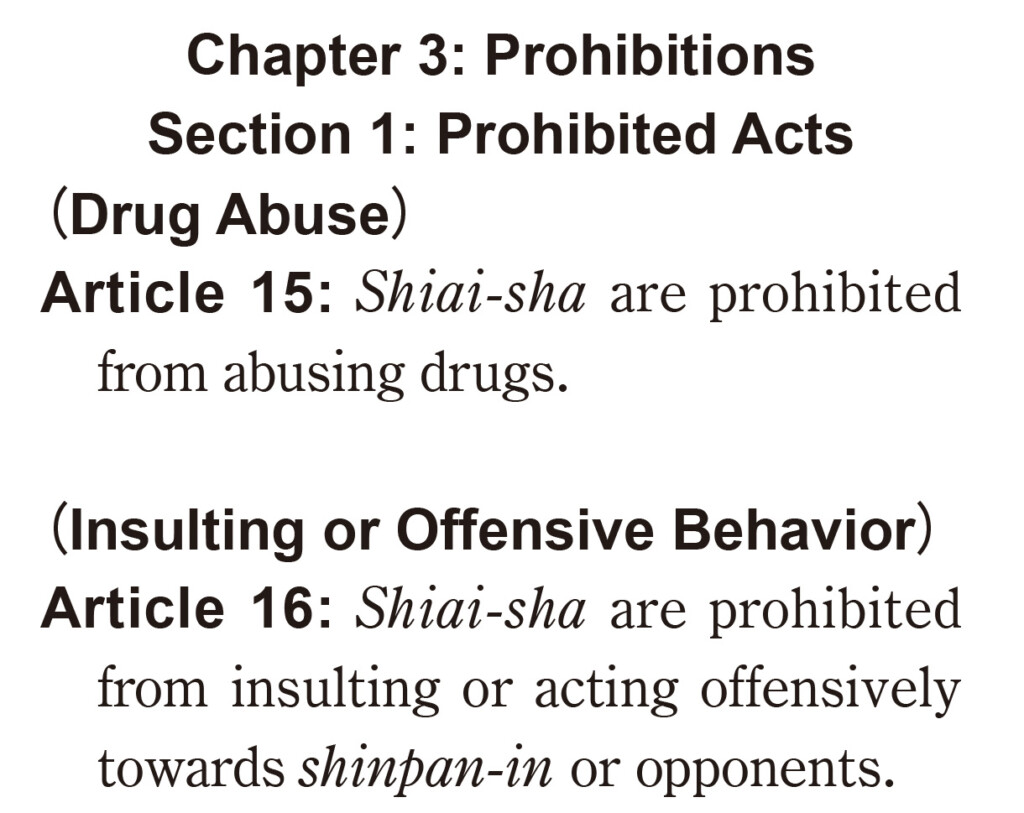

One crucial point I should add is that genuine kiai although aggressive, should never be confused disrespectful yelling. Unsportsmanlike vocalisations are strictly prohibited in competitive kendo, as they are in all budo, and will/should be swiftly penalised. This serves as a timely reminder that martial prowess and good manners are by no means mutually exclusive.

Kakegoe also serves tactical purposes. Old teachings identified three strategic “voices”: shouting loudly after scoring intimidates opponents into cautious defence; shouting when pressing forward panics opponents into careless counters; and shouting while under pressure signals to your opponent you see through their tactics, planting doubt. For example, Miyamoto Musashi’s Gorin no Sho (Book of Five Rings), he describes the “three cries” or types of vocalisations used in strategy:

“The ‘three cries’ bellowed before, during and after an encounter are distinctive. The method of shouting depends on the situation. A cry is a vocalisation of one’s life force. We roar against fires, the wind and the waves. The cry reveals the degree of someone’s vitality. In large-scale strategy, we roar at the enemy with all our might at the commencement of battle. Vocalisations lower in pitch are emitted from the bottom of the gut amid combat. Then we bellow with gusto in victory. These are what are referred to as the 'three cries.' In individual combat, yell Ei! while feigning an attack to lure the opponent into making a move, and then follow up with a blow from your sword. Roar to pronounce victory after the enemy has been felled. These are known as the “before-after cries.” Do not cry out loudly as you strike with your sword. If you emit a cry during the attack, it should be low in tone and match your cadence. Study this well.”

Yes sir, Musashi sir! Yet ultimately, kiai or kakegoe isn’t forced. Genuine kiai naturally arises from a calm centre, sometimes intentionally summoned but never mechanically produced. Done properly, kiai reinforces internal energy, asserts authority, coordinates precise movements, and complements technique, adding visual confidence to every action. That said, some modern schools of budo encourage quiet training, especially among younger practitioners, arguing excessive shouting disrupts breathing and wastes energy. Iaido (the art of sword drawing) offers an especially vivid illustration of this. Most iaido schools carry out their techniques in total silence, communicating their intensity solely through the fierce expressions and thunderous scowls etched across their faces. My own school, Hōki-ryū, is the notable exception: we punctuate every kata with explosive shouts that invariably disrupt the Zen-like serenity of any demonstration. We’re the iaido equivalent of an uncle who loudly cracks jokes at a funeral—annoying to everyone else but thoroughly convinced of our own charm.

But, we Hōki-ryū zealots should take heed. As another old poem gently warns:

“The kakegoe is but the shadow of true kiai—

the heart, in silence, breaks a sweat.”[3]

Turns out, in budo, volume isn’t everything. Sometimes the loudest message comes through in silence.

At the end of the day, many budo practitioners haven’t the foggiest notion what they’re shouting as kiai or kakegoe their way through a fight, and that’s perfectly understandable. These cries rarely carry precise meanings or carefully chosen words; they’re more like guttural expulsions dredged up from some internal well of primal instinct. The resulting noise is highly personal, often surprising even its maker. Translation isn’t just unnecessary, it’s impossible. The meaning lies entirely in the force of feeling behind it. In fact, stepping into a dojo during training, where everyone is enthusiastically bellowing their own unique vocalisations, resembles nothing so much as stumbling into an aviary filled with agitated, exotic birds: strange, noisy, and oddly mesmerising in their bewildering cacophony.

Ultimately, kiai and kakegoe is personal: shout boldly, even if you’re secretly channelling a constipated goose. After all, it’s authenticity counts.

[1] 「気合とは風を握って そのままに 足をとどめて鼻によくきけ」( Kiai to wa kaze o nigitte, sono mama ni ashi o todomete hana ni yoku kike) Ueda Raizō, Kenjutsu Ochiba-shū, contained in Imamura, Yoshio et al., eds. Kindai Kendō Meicho Taikei, Vol. 5. (Dōhōsha Shuppan, 1986) p. 185

[2] Ibid. 「気合とは物皆聞くな 寝な起きな 泣いて笑うた哺乳児に問へ」(Kiai to wa mono mina kiku na, ne na oki na. Naite warōta honyūji ni tou e.)

[3] 「懸声は真の気合の影にして 心にてかく汗ぞたつと」 (Kakegoe wa shin no kiai no kage ni shite, kokoro nite kaku ase zo tatsu toki). Nakajima Kenzō, Bokken Oyobi Naginata Taisō-hō (Meguro Shoten, 1918) p. 149

No comments yet.