Budo Beat 30: Duelling Crabs and Lessons in Kufū

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

I was just in Idaho attending a rather splendid Nito Kendo seminar. One might rightly wonder how a hundred earnest kendoka, each suddenly brandishing two swords instead of one, could achieve any form of martial coherence. Yet somehow, under the watchful guidance of Fujii-sensei and his trusted band of assistants, confusion gradually yielded to pockets of revelation. The instructors wisely abstained from spoon-feeding their charges; instead, they nudged everyone gently yet insistently toward thinking outside the box, each participant tasked with solving their own technical and conceptual riddles.

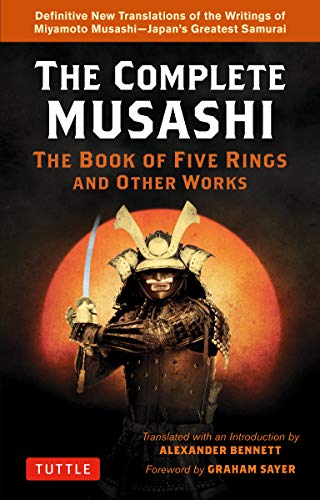

Watching the fascinating spectacle of ‘duelling crabs’ unfold, the Japanese word kufū (工夫) came to mind. It’s not exactly budo jargon, but you here it a lot in in the dojo. Miyamoto Musashi himself was fond (exceedingly so, in fact) of this little gem, scattering it rather liberally through the pages of his Gorin-no-Sho.

Photo by Alf Tan.

Literally, the word comprises two characters: 工, meaning “craft” or “construction”, and 夫, a “person” or “worker”. Originally, it suggests something akin to “a person diligently at work”. An individual grappling earnestly with their materials, shaping them through persistent, thoughtful effort. In budo, these “materials” might be some troublesome technique, kata, strategy, or even one’s own temperament. Thus, the word captures that spirit of personal experimentation, adaptation, and continuous refinement lurking at the heart of budo practice. If I had to render it into English, I’d say something along the lines of “trial-and-error refinement” or “innovation”.

What makes kufū particularly resonant in this context is the emphasis it places squarely on the practitioner’s shoulders, not the instructor’s. Fujii-sensei could point the way, certainly, but each practitioner had to forge their own path to understanding what they needed to do. The secret lies not simply in following prescribed patterns, but rather in dissecting them, rearranging the pieces, and constructing something personal from them. In light of a previous post I did on the concept of hyakuren jitoku (you can access the blogpost here), this is the difference between merely repeating and becoming an active craftsman of your own budo. It is, in the end, not just technical training but an intimate manifestation of perseverance and using your brain. In a way, hyakuren jitoku and kufū make the perfect, rounded couple. Two sides of the keiko coin.

Let me break it down further. In the context of budo, kufū embodies more than just ingenuity or diligent, creative effort. It represents the silent work that occurs during and between formal keiko. In other words, the trial-and-error tinkering in your mind and body as you replay a sensei’s instruction, test an idea, or wrestle with some technical or philosophical impasse. Kufū isn’t usually a short process; it’s a long and often lonely detour that transforms rote repetition into meaningful skill.

The path of budo is rarely straight. It winds, dips, and doubles back. But that’s what makes the journey rich, surprising, and worth every step.

When you venture deeper into budo, you find it’s less about physical prowess and more about a meandering mental odyssey. This is the fun stuff. It’s a lifelong dialogue between mind and body, a perpetual negotiation between intention and action. Beneath each strike or throw lies a dense network of decisions; a quiet calculus involving timing, distance, and purpose. The casual observer sees only surface violence; the practitioner navigates an intricate mental chess game, balancing clarity of intention and development of character, qualities far more enduring than one-off victories. In this sense, the greatest opponent is always the self.

A key idea here is to “hold doubts” about what you are being taught and work out a way to reconcile this and make it work for you. A classic verse from budo lore encapsulates this well:

“Train with enough doubt that it drives deep kufū;

what you unravel through that struggle becomes your real insight.”[1]

This condensed wisdom speaks volumes about budo training. You must question deeply and use doubt as a catalyst for growth. Doubt ensures complacency never settles in; each movement must be reconsidered and perfected through rigorous contemplation and action. Doubt is the gritty spice that makes your budo stew palatable, feeding kufū and turning dull routine into a feast of personal epiphanies.

Moreover, kufū isn’t necessarily about practising harder, but smarter. It means adjusting, reflecting, and improving with every iteration. Without kufū, budo stagnates; with it, keiko (and beyond) becomes a dynamic laboratory.

Observing budo closely reveals a tension between disciplined routine and creative improvisation. Technique must become second nature, through hyakuren jitoku = lots and lots of practice; yet it must also be continually questioned with the mindset of kufū = how can I make this better?

Budo teaches resilience, mostly by forcing you into regular, uncomfortable self-examinations. Setbacks aren’t failures. They’re just highly instructive inconveniences. That well-worn adage, “Fall down seven times, stand up eight”, isn’t merely motivational twaddle to instil a never-say-die attitude; it’s an essential budo survival strategy. But here’s the catch: it only works if seasoned liberally with kufū. As one of my sensei impressed upon me recently, “The artistry we are all after stays forever tantalisingly out of reach, neatly sidestepping arrogance and embracing humility instead.”

“The blowing wind, the snow, the hail, the blooming flowers all become part of one’s kufū in the diligent pursuit of your art.”[2]

In other words, these natural phenomena aren’t simply picturesque distractions. They symbolise the unpredictable elements inherent in any journey. A practitioner of budo constantly confronts shifting circumstances and unexpected challenges (just as one navigates changing weather) and learns to use each obstacle or opportunity as a chance for deeper understanding, improvisation, and growth. Kufū thrives precisely because conditions are rarely ideal or predictable.

Perhaps the true beauty of budo lies in this paradoxical balance: it’s structured yet flexible, disciplined yet spontaneous, rigorous yet liberating. Engaging in budo, therefore, demands an open-minded acceptance of life’s complexities, turning even the most mundane detail into fertile ground for creative insight and continuous refinement.

“If in quiet moments you diligently cultivate the concept of kufū, your heart will remain unperturbed when the moment of truth arrives.”[3]

After all, budo (much like life) is essentially an exercise in cheerful pragmatism. Musashi understood this clearly: to expect perfect conditions is foolish, but to adapt creatively to chaos… now that’s a mark of genuine progress.

[1] Tomita Yoshinobu (ed.), Shiryō Nihon Kendō, (Tomita Yoshinobu, 1982) p. 107

[2] Kumamoto Jitsudō, Budō Kyōhan, (Buyōkan, 1895) p. 108

[3] Murakami Teiji, Kendō Nyūmon, (Airyūdō, 1956) p. 165

No comments yet.