Budo Beat 18: The History of Zanshin (Part 1)

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

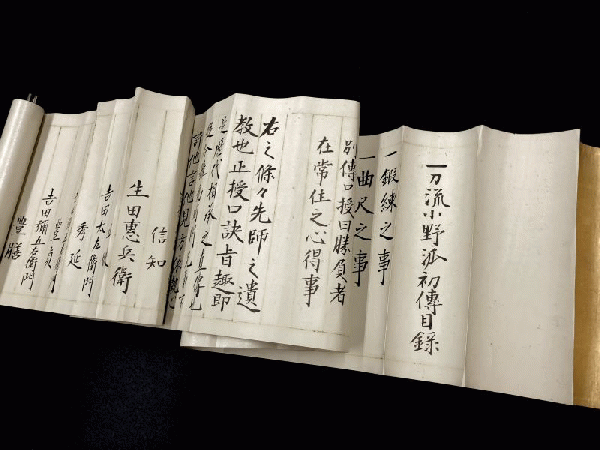

The following is No. 2 of my 25-article series titled “The Philosophy of Zanshin” (残心の哲学) published in Japanese in the Nippon Budokan’s monthly magazine, Gekkan Budo (“Budo Monthly”, February 2023, pp. 56-61). It’s a rough translation, but I hope it offers some insight. You can read No. 1 here.

Introduction

Zanshin is a cornerstone principle in modern budo, embodying a profound integration of educational philosophy and practical martial application. Despite its prominence today, the concept of zanshin was scarcely mentioned among martial arts traditions during the Edo period (1600–1868). Moreover, early Edo-period martial treatises that do refer to zanshin present a mosaic of differing interpretations, suggesting a complexity often overlooked in contemporary understanding. Remarkably, despite the ubiquity of zanshin in contemporary budo discourse, no comprehensive historical examination of the term and its evolution across diverse martial arts traditions has previously been undertaken—neither in Japanese nor English scholarship. This article, therefore, represents the first extensive effort to trace and analyse the historical nuances of zanshin, exploring and comparing representative texts up to the mid-Edo period to illuminate the diverse meanings, subtle nuances, and evolving significance historically associated with the concept.

Early Historical Context and Usage

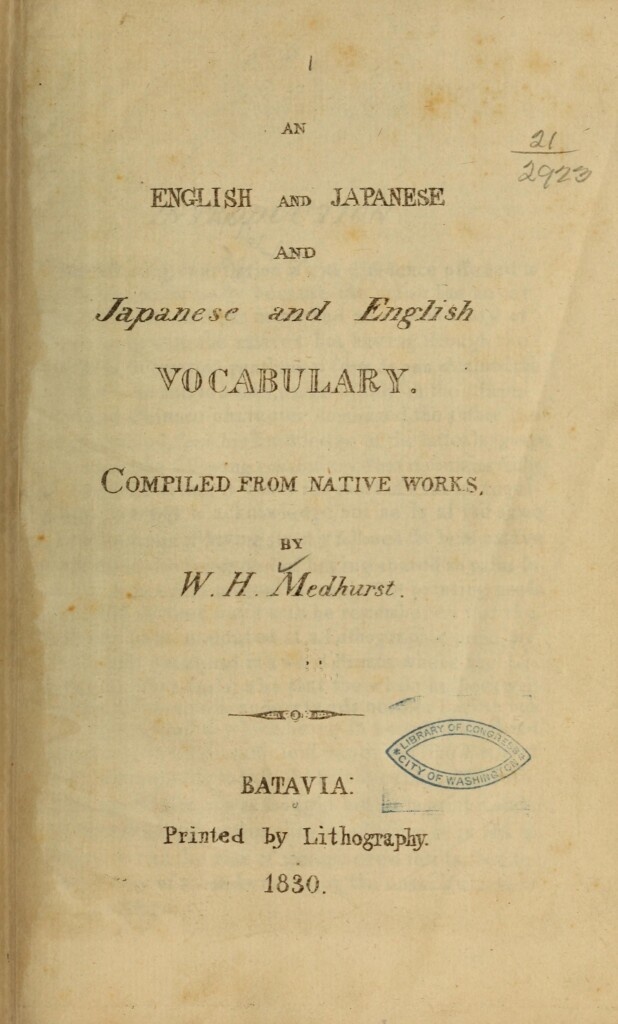

Although the term zanshin appears in Japanese literature from ancient times, its meaning differs significantly from what modern budo aficionados understand it to be. The earliest English-Japanese dictionary to include an entry for zanshin defines it as “san-sin 残心 A cruel mind”.[1] Japanese dictionaries also confirm a similar negative interpretation. For instance, the Wakan Gazoku Iroha Jiten (1899) defines zanshin “lingering regret, frustration”, without mentioning martial arts at all. Furthermore, I understand that in China, the term is reportedly associated with meanings such as cruelty or regret.

Though zanshin does not appear to have been widely used in martial arts parlance before the modern period, instances can still be found in certain traditions.[2] Needless to say, any form of complacency and carelessness are unacceptable in the context of combat. Historical teachings frequently emphasise caution, exemplified by Hōjō Ujitsuna’s famous phrase, “Tighten your helmet cords after victory” (Hōjō Ujitsuna-kō O-kakioki). This maxim warns warriors not to become intoxicated by their successes and urges continued vigilance against potential counterattacks. Such lessons advocating constant alertness, as zanshin is generally understood today, are numerous. Nevertheless, historically, the term did not necessarily refer specifically to this state of mind.

Zanshin in Early Edo-period Military Texts

The term zanshin appears in an early 17th-century military strategy text, Kōyō Gunkan Hyōban. This work describes two mental attitudes—zanshin (残心, vigilant mind) and kanshin (閑心, calm mind)—as strategies for responding effectively to changes in the enemy’s actions and the battlefield situation. Specifically, it states: “Zanshin means maintaining vigilance after battle, carefully watching for any changes from the enemy. Kanshin, meanwhile, denotes restraining oneself and calmly assessing the timing of action and inaction.”[3]

In this text, kanshin refers to maintaining composure and clarity of mind even amid chaos and confusion. In contrast, zanshin carries connotations closer to what might be described as a “non-engagement strategy” or “strategic retreat.” Withdrawal involves resisting the temptation to immediately respond to an aggressor when confronted by a formidable enemy, instead buying time to recover strength or gain clearer perspective. The text suggests that, occasionally, the greatest gains are achieved precisely by doing nothing. In a sense, this zanshin could be defined as “leaving your heart out of it”.

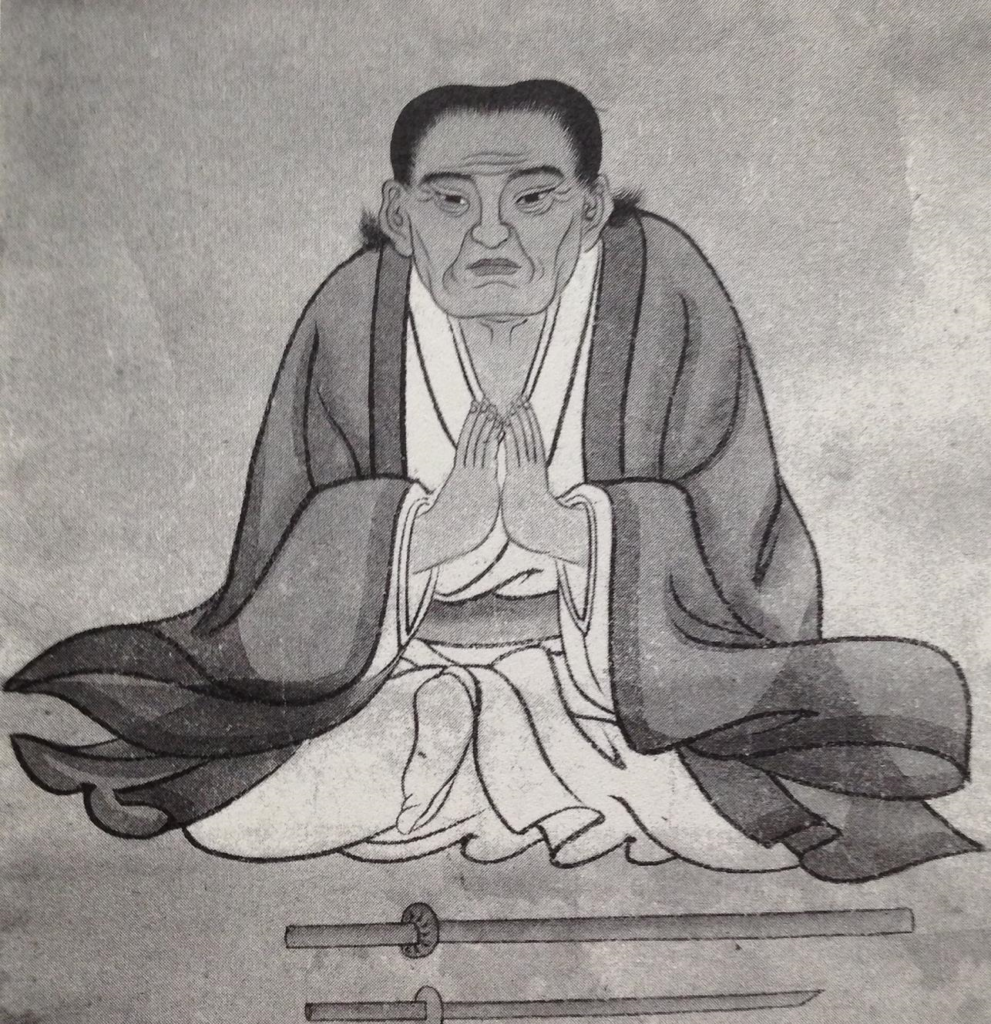

Miyamoto Musashi’s Perspective on Zanshin

Among martial arts treatises that mention zanshin, Miyamoto Musashi’s Hyōhō Sanjūgo-kajō (1641), Yagyū Munenori’s Heihō Kadensho (1632), and Yagyū Jūbei’s Tsuki no Shō (1642) immediately come to mind.[4] Musashi describes zanshin and hōshin (放心, releasing the mind) as follows:

“Zanshin (lingering mind) and hōshin (released mind) depend upon the situation and timing. When holding your sword, usually maintain intentional awareness (i no kokoro). However, when decisively striking an enemy, release your inner mental state (kokoro no kokoro) while still preserving your intentional focus. There are various interpretations of zanshin and hōshin—you must carefully consider the distinction.”[5]

Musashi divides the concept of “kokoro” into two distinct layers: i no kokoro (意のこころ) and kokoro no kokoro (心のこころ). The former (i no kokoro) can be interpreted as outward-directed spirit or active intention, while the latter (kokoro no kokoro) represents one’s inner core, deeper spirit, or mind. In combat, Musashi instructs practitioners to release (hōshin) their active intention outward, seizing the initiative and flexibly (lightly) responding to the enemy’s movements, while firmly (heavily) retaining their inner core. When delivering a decisive strike, one releases the deeper, inner mind (kokoro no kokoro) while retaining active intention (i no kokoro) in order to stay prepared. Thus, even in striking, one mind is released (hōshin) and the other retained internally (zanshin) as defence against counterattacks.

Musashi presented his Hyōhō Sanjūgo-kajō in 1641 to Hosokawa Tadatoshi, lord of the Kumamoto domain. Tadatoshi was a highly skilled disciple of Yagyū Munenori, who, having mastered the deeper teachings of Shinkage-ryū, received Munenori’s Heihō Kadensho in 1637—one of very few people to do so. Interestingly, Heihō Kadensho itself contains only a brief reference to zanshin: “Regarding zanshin, it is used in both attack and waiting. Details to be transmitted verbally.” Thus, Munenori left the specifics unwritten, deliberately retaining them as oral teachings.

It is reasonable to speculate that Tadatoshi, intrigued by this secretive concept, may have sought Musashi’s perspective after inviting him to Kumamoto in 1640. Musashi’s response was codified explicitly in the Hyōhō Sanjūgo-kajō. Yet notably, Musashi omitted direct reference to zanshin and hōshin from his final work, the Gorin-no-sho (Book of Five Rings), completed in 1645, suggesting he chose not to publicly disclose these nuanced concepts further. Or, maybe he just forgot!

The Yagyū Shinkage-ryū and Ittō-ryū Traditions

Yagyū Jūbei compiled the teachings of his grandfather, Yagyū Sekishūsai, and his father, Yagyū Munenori, into the text Tsuki no Shō. Within this work, zanshin is explained in considerable detail, indicating its central importance in the Shinkage-ryū tradition. Jūbei emphasises:

“Whether you have struck successfully or missed, whether you seize the initiative or withdraw, advance or retreat—in both your posture and gaze, never allow even the slightest lapse in vigilance; preserving your awareness (zanshin) is of utmost importance. […] The mindset of ‘letting go of one move and preparing immediately for the next’ also embodies the continuous contemplation of many future possibilities.”[6]

Further, Jūbei states: “Generally speaking, the essence lies in adopting a mindset of zanshin, maintaining the presence of mind and readiness to appropriately respond to whatever happens, even when you fail to land your strike.”

This teaching closely resembles the modern understanding of zanshin in contemporary budo, emphasising continuous vigilance and readiness for all eventualities. Additionally, zanshin appears frequently in teachings of the Ittō-ryū, another major school from the Edo period. However, because this style has numerous branches, nuances of the term differ somewhat even within the same tradition, depending on the source.

For example, Kotōda Toshisada’s Ittōsai Sensei Kenpōsho (1664) includes the following passage:

“Utsuri (移, shifting) is like the moon reflecting onto the water. This is called the position of hōshin (捧心, presenting heart), meaning to ‘approach.’ Utsushi (写, reflecting) is like the water capturing the reflection of the moon. This is called the position of zanshin (lingering heart), meaning to ‘separate’.”[7]

According to Takeda Ryūichi and Nagao Naoshige, this rather nebulous teaching can be interpreted in the following way:

“Actively shifting toward the opponent (utsuri) requires a rational defence grounded in principle, while passively capturing the opponent’s form without intention (utsushi) demands the skilled execution of technique to attack effectively. In our tradition, the former position (utsuri) is transmitted as the hōshin no kurai (‘position of offering the heart’), and the latter (utsushi) as the zanshin no kurai (‘position of lingering awareness’). When illustrating these principles through logical reasoning, we employ the metaphor of suigetsu no denju (‘transmission of the moon reflected in water’).”[8]

In this context, “hōshin” as its characters literally suggest, is the offering of one’s heart—uniting oneself completely with the opponent and shifting one’s spirit into them to discern their intent. “Zanshin” here means to spontaneously capture the opponent’s appearance without conscious intention (mushin), defending against their attacks while simultaneously counterattacking. Moreover, the Ono-ha Ittō-ryū’s Ittō-ryū Heihō Kana-gaki (1692) provides the following explanation of zanshin:

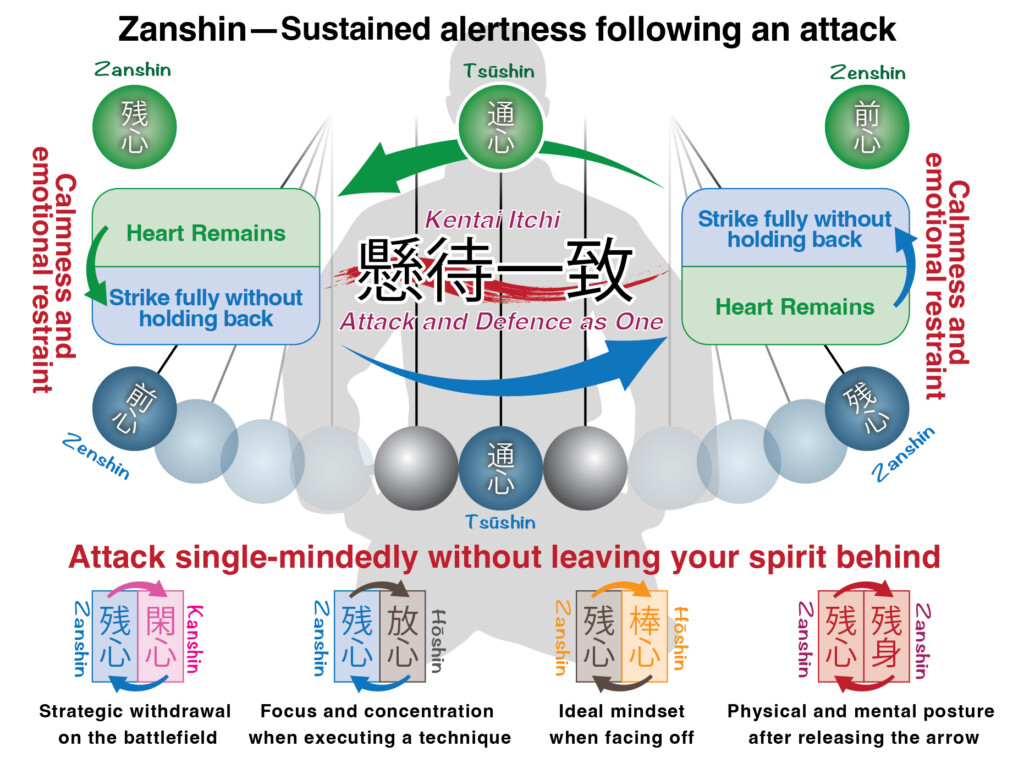

“At the moment of victory, you must not pause even a single step nor leave behind any lingering attachment; discard all extraneous thoughts and maintain an unwavering state of total concentration. Although we teach the concept of zanshin, it primarily serves during training as a corrective measure against deviations in technique, excessive tension, and overly competitive behaviour. Once this understanding is attained, however, it is vital to embody zanshin precisely at the decisive moment of victory. Concepts such as kenchū-tai (attack within defence) and taichū-ken (defence within attack) resemble zanshin, yet differ fundamentally from hesitation (zannen). Maintain your spirit without lingering attachments and never slacken at the critical point of victory. Should your opponent perceive hesitation and attempt a counterattack, your movements must never become excessive or uncontrolled. Constant practice is thus of utmost importance. Indeed, you must be mindful that lingering attachments at the moment of victory can inevitably arise.”[9]

When the moment to attack arrives, one must commit wholeheartedly, without reservation. The concept of kenchū-tai, taichū-ken (unity of attack and defence) teaches that offence and defence are inseparable: even while attacking, one must never lose readiness against the opponent’s counterattack; similarly, even while defending, one must always remain poised to seize opportunities for offence. Techniques used to strike an opponent must simultaneously serve as defensive movements, and defensive techniques must equally function as attacks (kentai itchi). With full awareness (zanshin), one does not merely guard against an enemy’s counterattack or offensive move; rather, one responds actively, transforming defence immediately into counter-technique and vice versa.

Moreover, Ono-ha’s Heihō Jūni-kajō (1689) states:

“Leave no attachment in your mind; strike so that awareness naturally remains (zanshin). For instance, when you calmly and steadily pour water from a teacup, it empties completely, leaving not a single drop behind. But if you abruptly turn the cup upside down and then immediately right it, some water inevitably remains within. Following this logic, in our tradition, the wooden sword (bokutō) is decisively cut all the way down, without interruption. It is with this principle in mind that you must cultivate the practice and experience of zanshin.”[10]

Thus, when one commits fully—leaving nothing behind physically or mentally—in an attack, zanshin emerges naturally as a byproduct. In other words, rather than deliberately leaving your mind behind, genuine zanshin arises spontaneously precisely because you attack with undivided focus and total commitment.

Applications Beyond Swordsmanship

Thus, zanshin encompasses various interpretations and carries multiple layers of meaning. In Kōyō Gunkan Hyōban, it is presented as a tactical strategy—disengaging from battle temporarily to observe and evaluate the enemy. Miyamoto Musashi approaches zanshin psychologically, emphasising the need to maintain concentration and discern intent while engaging an opponent. Shinkage-ryū describes zanshin as maintaining constant vigilance even after an exchange has concluded. Meanwhile, Ittō-ryū likens the concept to the moon reflected on water, symbolising a mental state free from attachment to the enemy. Additionally, by attacking wholeheartedly without consciously holding anything back, one’s mind paradoxically remains alert, ready to adapt or continue as necessary. In other words, what matters most is the mental readiness before a strike rather than afterward. Although paradoxical, the more completely one invests oneself in an attack—without deliberately trying to retain awareness—the more naturally zanshin emerges, allowing the practitioner to freely and fluidly respond to personal errors or an opponent’s counterattacks.

Examples of zanshin extend beyond swordsmanship traditions. In the context of spear techniques, for instance, the Hōzōin-ryū Jūmonji-kama Hyōhō Hyakushu (1686) warns practitioners in a poem: “If your zanshin focuses only ahead, faults will inevitably appear behind.”[11]

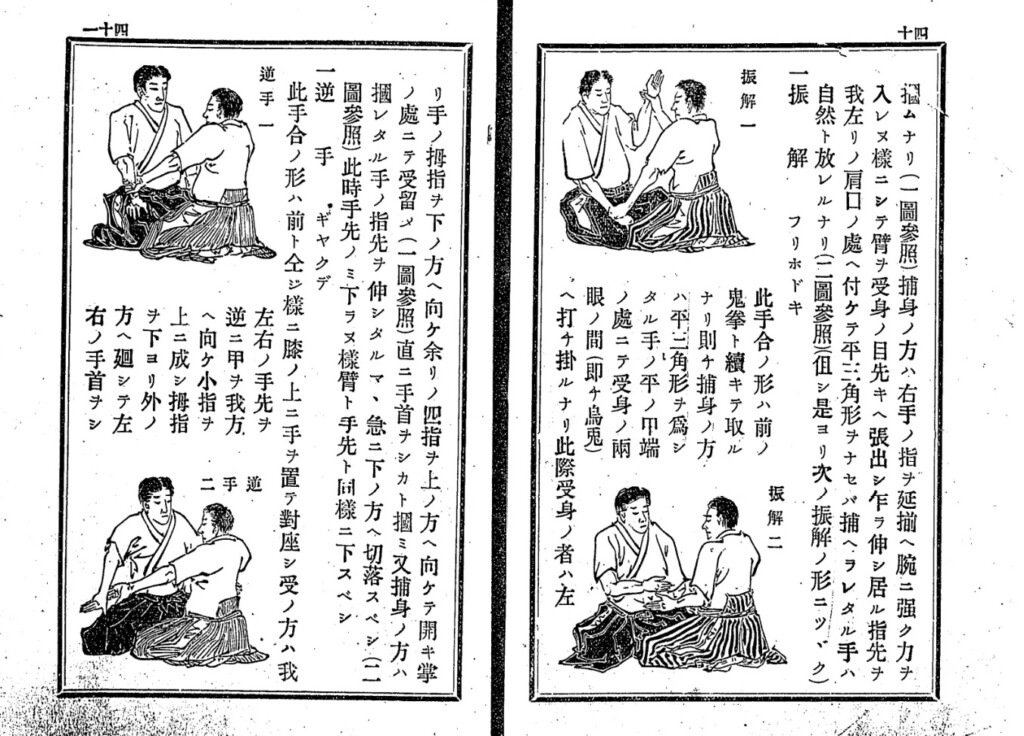

This accentuates the necessity of maintaining mental vigilance in all directions to avoid negligence. Additionally, in Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū Jūjutsu teachings, the mental framework for executing techniques is divided into three distinct phases: zenshin (preparatory mind), tsūshin (going mind), and zanshin (lingering mind). According to Yoshida Chiharu and Iso Mataemon’s Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū Jūjutsu Gokui Kyōju Zukai (1893):

“Zenshin refers to the mental state from the initial kakegoe (shout) up to the start of physical action. Tsūshin pertains to the mental functioning during the execution of the technique. Zanshin denotes the mindset maintained immediately after completing the technique, focusing one’s gaze and attention upon the opponent’s eyes.”[12]

Here, zenshin (前心, preparatory mind) refers specifically to the mindset when initiating action, beginning with the initial vocalisation (kakegoe) and preparing to move. Tsūshin (通心, going mind) indicates the state of mind during the execution of the technique itself. Lastly, zanshin (lingering mind) is defined as the mindset immediately after completing the action, when one shifts their gaze to carefully observe the opponent after the fact. These three mental states, combined sequentially, constitute the complete psychological flow necessary for executing a technique effectively.

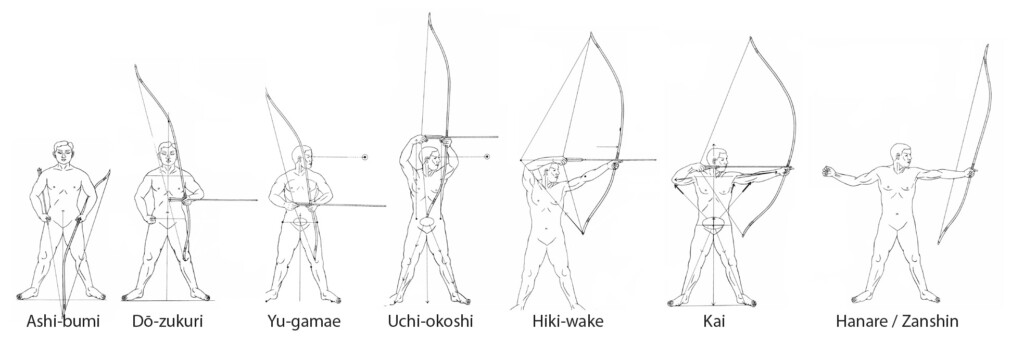

In modern kyudo (Japanese archery), the fundamental movements known as Shahō Hassetsu (“Eight Stages of Shooting”) conclude with zanshin (残身・残心, remaining posture and mind). Note here that ‘shin’ is written in two ways, 身 (shin = body) and 心 (shin = heart/mind). Thus, unsurprisingly, the concept of zanshin also appears in historical archery texts. For example, in the Gokan no Sho, a key manual of the Heki-ryū Chikurin-ha tradition annotated by Hoshino Kanzaemon Shigenori (1642–96), an explanation of zanshin was added in the volume titled “Shokan no Maki”:

“Also, zanshin means to retain one’s mind within the navel area. This is intended to prevent the torso and hips from rising excessively upward after releasing the arrow. Instead, one should keep the torso stable and balanced upon the hips, thereby retaining mental focus at the body’s centre of gravity.”[13]

In this context, zanshin specifically denotes maintaining physical and mental equilibrium and stability at the moment of releasing the arrow. Unlike swordsmanship or jūjutsu, kyudo does not involve direct combat with an opponent. Consequently, its concept of zanshin (remaining posture and mind) is less about practical fighting and more reflective, ritualistic, and introspective—centred around the idea of “facing oneself.” Emphasis is placed on maintaining a dignified, graceful posture and composed mental state from beginning to end, without ever losing focus or discipline irrespective of the result of the shoot.

Moreover, the Bijinsō Hika, a poetic manual of the Heki-ryū Chikurin-ha tradition, states: “In archery, there are three important moments; transmit each carefully through oral teachings.” These “three moments” (mitsu no narai) refer specifically to: the initiation of drawing the bow, entering into full draw (kai), and the state after releasing the arrow (zanshin). Thus, rather than emphasising practical application, the focus here is on demonstrating elegance, refinement, and spiritual poise.[14]

A similar concept emphasising refinement and dignity appears in the tradition of tea ceremony. Ii Naosuke (tea name: Sōkan), lord of Hikone domain, authored the Chayu Ichie-shū (1858) and is credited with popularising the now-famous tea philosophy of ichi-go ichi-e (“one encounter, one opportunity”). In it, he describes the etiquette of bidding farewell, known as yojō zanshin (余情残心)—a lingering feeling of appreciation shared between host and guest:

“Dokuzakan’nen (Reflections when sitting alone): Both host and guest, sharing a lingering sentiment (yojō zanshin), conclude the exchange of farewell greetings. When guests depart through the garden path (roji), they should avoid raising their voices, quietly turning back with a reflective glance as they leave. Even more so, the host should respectfully continue watching, seeing off the guests until they are completely out of sight.”[15]

Thus, in tea ceremony, zanshin symbolises refined awareness, emphasising the graceful, mutual appreciation and respect that persist even after the physical gathering ends.

As described above, teachings on zanshin vary significantly depending on the martial tradition. However, one important text that presents zanshin in a more generalised, cross-style manner is the Tengu Geijutsu-ron (1727). Its author, Niwa Jurōemon Tadaaki (Issai Chozan), was both a samurai of the Sekiyado domain in Shimōsa Province and a swordsman himself. Notably, neither his famous works, Neko no Myōjutsu (“The Cat’s Marvelous Skill”) nor Tengu Geijutsu-ron (“The Demon’s Sermon on the Martial Arts”), provide explicit instructions regarding technique or strategy. Instead, they aim primarily to guide martial artists inward, towards the inner path of personal development and spiritual refinement.

“Question: Many schools speak of zanshin, but what exactly does it mean?

Answer: Zanshin simply means not becoming fixated on the action itself, thereby keeping the essence of your mind unmoved. When your mental foundation is immovable, your response to any situation is naturally clear and adaptable. This holds true not only for martial arts but also for daily human interactions. Even if you deliver a powerful strike that seems to penetrate to the depths of hell itself, you remain unchanged from your original self. Thus, you retain freedom of movement in all directions without obstruction or hindrance. Zanshin does not mean deliberately preserving or leaving behind your consciousness. If you consciously attempt to hold back your awareness, your mind will become divided. Moreover, without clearly establishing your mental foundation, you’ll merely strike or thrust blindly. Clarity arises naturally from an unmoving mental foundation. Therefore, you must strike clearly, thrust clearly, and nothing more. This teaching is extremely difficult to grasp. If misunderstood, it can lead to grave errors.”[16]

In other words, when a practitioner asks the Great Tengu about the various meanings of zanshin taught by different martial schools, the response highlights that true zanshin involves maintaining an immovable core of the mind, unattached to technique. With this unmoving mental core, one’s actions remain clear and responsive. Even after executing the deepest cut, one’s fundamental state remains unchanged. Thus, freedom of movement remains unhindered. Attempting deliberately to preserve one’s awareness, however, creates duality in thought, resulting in confusion or blind actions. True clarity, the Tengu explains, arises spontaneously from a stable, unmoving mind. However, the passage concludes with a warning: misunderstanding this subtle teaching can lead to serious harm.

That means, by maintaining an immovable core of the mind no matter what occurs, one can always respond or act in the most appropriate manner. This explanation closely resembles the concept of heijōshin (equanimity or ‘ordinary mind’) and even carries spiritual overtones. Interestingly, the teaching underlines that regardless of the outcome—whether one’s technique succeeds or metaphorically plunges into the depths of hell—the practitioner’s mental state must remain unaltered and calm. Thus, zanshin, as explained here, underscores the absolute necessity of emotional control. It offers a profoundly philosophical yet intensely practical interpretation of the concept.

Summary

As suggested by the statement “Various martial schools speak of zanshin”, it is clear that by the mid-Edo period, zanshin had firmly established itself within martial arts practice and philosophy, influencing numerous schools and traditions. Over time, just as budo culture evolved, the concept of zanshin underwent significant transformations, developing deeper layers of meaning and application. Today, it is widely recognized as a critical element within modern budo, particularly within discussions addressing the longstanding tension between “character formation” and a “win-at-all-costs mentality.”

However, this contemporary debate is far from novel. As early as the mid-Edo period, martial artists grappled with similar concerns. The rise of rigorous training methods, such as uchikomi-geiko (full-contact sparring using protective equipment), and the popularity of competitive gekiken (sparring) matches heightened the tendency among practitioners to pose or celebrate immediately after delivering a successful strike—a practice known as hikiage. This behaviour, reflecting overconfidence and carelessness, became problematic and was consistently criticized by martial arts masters and authorities. Recognizing the dangers inherent in such complacency, martial traditions began to systematically incorporate zanshin as an essential criterion for determining valid victories. By explicitly requiring practitioners to demonstrate continued vigilance, even after achieving apparent victory, zanshin reinforced humility, discipline, and mental preparedness. The subsequent historical development and detailed implications of incorporating zanshin into martial practice and competition will be further explored in the following article.

[1] Henry Medhurst, An English & Japanese, and Japanese & English Vocabulary, Compiled from Native Works, 1830, p. 313.

[2] The modern period in Japanese history refers to the era beginning in the late 19th century, following the Meiji Restoration of 1868. During this period, the shogunate was replaced by an imperial government, prompting Japan to embark on rapid modernisation. The Meiji period (1868-1912) marks the transition from classical martial arts to modern budo.

[3] Takeda-ryū Gungaku Zensho, Jin, 1935, p. 141

[4] Miyamoto Musashi authored the treatise Heihō Sanjūgo-kajō in 1641 for Hosokawa Tadatoshi, daimyo of Kumamoto. Likely inspired by Yagyū Munenori’s earlier gift, Heihō Kadensho, Musashi’s text serves as a valuable complement to his renowned Gorin-no-sho, enriching our understanding of his swordsmanship philosophy.

[5] Reproduced in Bujutsu Sōsho, (Kokusho Kankokai, 1915) p. 231

[6] In Nihon Budō Taikei, Vol. 1, edited by Imamura Yoshio et al., (Dōhōsha, 1982) p. 166

[7] Note that this ‘hōshin’ (捧心) is different to the hōshin used by Miyamoto Musashi (放心).

[8] Takeda Ryūichi and Nagao Naoshige, Ittōsai Sensei Kenpōsho Yakuchū: Kengō Itō Ittōsai no Oshie (Benseisha, 2022) p. 8

[9] Ueda Raizō, Kenjutsu Rakuyōshū reproduced in Kindai Kendō Meicho Taikei, Vol. 5, edited by Imamura Yoshio et al., (Dōhōsha, 1986) p. 235

[10] Ibid., p. 233

[11] Imamura Yoshio, Budō Kasenshū, Vol. 1, (Daiichi Shobō, 1989) p. 402

[12] Yoshida Chiharu, Iso Mataemon, Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū Jūjutsu Gokui Kyōju Zukai (1893), p. 23

[13] Imamura Yoshio et al., Nihon Budō Taikei, Vol. 4, p. 201

[14] Imamura Yoshio et al., Budō Kasenshū, Vol. 1, p. 293

[15] Okuda Shōzō ed., Chayu Ichieshū, (1936), p. 101

[16] Reproduced in Budō Hōkan, edited by Dai-Nippon Yūbenkai Kōdansha (1934), p. 628

No comments yet.