Budo Beat 29: “Ken-Tai Itchi” and Turning Trouble into Triumph

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

As I do every year, I recently went to the Iadera Kendo Seminar in Zadar, a charming seaside town in Croatia where I had the pleasure of jousting with practitioners from 19 different countries. Amid with the stunning backdrop and international camaraderie, I noticed many of the lower-ranked kendoka had an annoying habit of blocking and retreating before falteringly launching their own attacks. It makes it near impossible to engage, and having to chase after younger opponents gets a bit wearisome for these aging bones. This irksome pattern prompted me to repeatedly stress to them that, if they genuinely wanted to improve, they needed to embrace the idea that the “best form of defence is offence”, and to simply go for it instead of away from it.

If you’ve spent any reasonable amount of time in a dojo, you’ve likely come across a paradox that makes perfect sense to seasoned practitioners of budo: ken-tai itchi (懸待一致). It literally means unity of attacking and waiting. There is another similar term, kōbō itchi (攻防一致) which literally means attack and defence together, but ken-tai itchi seems to be the predominant term, at least in my circles.

The famous Edo period sword expert, Minamoto Kiyomaru wrote regarding ken-tai, “If you merely wait, it becomes difficult to transition into an attack. If your intention is solely aggressive, your mind becomes restless. Therefore, attack within waiting, and wait within attacking.”[1] Ken-tai itchi is often explained along the lines of the popular sporting adage, “the best defence is offence.” But there’s an essential difference: while the sporting cliché advocates aggressive strategies to dominate opponents, ken-tai itchi emphasises mindful balance and integration. The goal is not merely to overpower, but to maintain a continuous, adaptive flow between attack and defence, offence and caution.

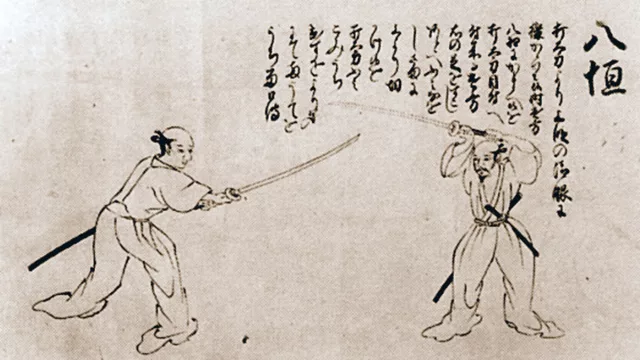

Miyamoto Musashi uses the two kanji of ken and tai when he talks of the “initiatives” (sen) in combat in the Fire Scroll of Gorin-no-sho.

“Of the three initiatives, the first is to initiate the attack before the enemy does. This is called ken-no-sen (懸の先). The second initiative is to attack the enemy after he initiates first. This is called tai-no-sen (待の先).The third initiative is to attack the enemy as he attacks you. This is called tai-tai-no-sen. These are the three initiatives. Regardless of the method of combat, once a fight is underway there are no other initiatives other than these three. Taking the initiative is the key to quick victory and is thus the most crucial aspect of combat strategy.”[2]

There’s another old saying:

“When attacking, never let your mind become careless. Within attack, there is defence; within defence, there is attack.”[3]

At first blush, it sounds suspiciously like telling someone to juggle chainsaws cautiously, which is good advice, but a bit tricky in practice. Yet, as with most maddeningly wise contradictions, the clarity of it strikes you immediately once swords start flying.

Take, for instance, an opponent who rushes forward in a frenetic flurry to smite you down. In kendo, for example the proper response is immediate, decisive, yet measured: a swift kiriotoshi to cut down the oncoming attack, or perhaps a deft suriage to deflect upwards, smoothly converting defence into attack. What appeared a mere reaction has now become a cunning strategy. This is ken-tai itchi in action—where defence transforms seamlessly into offence, as naturally as breathing.

Kiriotoshi is a sublime kenjutsu technique in which the practitioner cuts downward through the opponent’s attack with perfect timing and centre control, simultaneously deflecting the incoming blade and delivering a finishing blow. It embodies both offence and defence in a single, unified motion. The Ono-ha Ittō-ryū is famous for its amazing kiriotoshi techniques.

When you strike, your own weapon (be it a sword or your fists) simultaneously defends. That thrust meant to land conclusively on your opponent’s body also conveniently blocks their pathway of attack. Your offensive manoeuvre becomes your shield, and thus attack is defence incarnate. Engaging without this principle, your strategy degenerates into predictable aggression or stubborn caution. Predictability in budo, as in most arenas of human interaction, swiftly ends in defeat.

Ken-tai itchi is eloquently illustrated in the venerable treatise Heihō Kadensho, a classic manual that is as much philosophical poetry as martial instruction. It describes ken—the spirit of attack—as fierce intent emerging instantaneously upon engagement, a primal urge to strike first with uncompromising resolve. Tai—the essence of defence—is to hold back, cautiously observing, always vigilant and never impulsive. The author, Yagyū Munenori, insists these two apparently opposing states are not enemies, but companions, inseparable as light and shadow. The following quote is a little bit on the long side, but I think it gets the point across well.

“I shall now explain the details of ken (attacking) and tai (waiting), or put simply, offence and defence. First, ken means aggressively launching your strike the instant combat begins, beating your opponent to the initiative. But you must also recognise that your opponent carries the same aggressive intention.

Second, tai means not carelessly rushing into attack, but instead firmly awaiting your opponent’s committed strike. There are various strategies relating to these concepts of ken and tai: One such strategy is to attack with your body and limbs, while keeping your sword ready to defend. This approach draws your opponent into making the first move, allowing you to seize victory.

Another strategy involves controlling both your mind and body, balancing ken and tai for victory: First, keeping your mind in a state of waiting (tai) and your body poised to attack (ken). If your mind becomes overly aggressive, the urge to strike prematurely can lead to defeat. By tempering your mental aggression but keeping your body positioned offensively, you prompt your opponent to initiate the attack.

Conversely, you can place your mind in an aggressive state (ken), while outwardly presenting your body (or the sword held in your hands) as defensive (tai). In reality, your mind remains alert and poised to seize the initiative, thus allowing you to claim victory by surprising your opponent. Ultimately, both teachings—whether the mind waits and the body attacks, or the mind attacks and the body waits—share the same essential principle: enticing your opponent to strike first, and thereby securing victory.”[4]

Both Musashi and Munenori were active in the days when kenjutsu training was kata-centric, and definitely on the perilous side when bouts were conducted! Yet, as kenjutsu evolved into its competitive fencing form, with bamboo shinai and protective armour replacing real swords and life-threatening engagements, the delicate balance began to shift. Chiba Shūsaku, the Edo-period swordsman who was a pioneer in the development of the sparring style of kenjutsu, captured the delicate tension of balance when he taught: “Wait with the intent of striking; strike with the intent of waiting; advance with the intention of retreating.”[5] This way, these teachings made their way into the early competitive form of swordsmanship to maintain its true spirit of do-or-die shinken shōbu (real combat).

Nevertheless, what was to eventually become modern competitive kendo that we have now, with the limited targets of men (head), kote (wrists), dō (torso), and tsuki (throat), inevitably favoured defence. Strategies to avoid getting hit like sansho-yoke, a defensive stance raising the left fist above the head while shifting the body slightly to the right, started to become popular. Though rooted in older martial traditions, this posture became emblematic of defensive excess in modern competition.

I remember the days when sansho-yoke (the 3 target block) was an occasional tactical curiosity until a high school team famously used it to clinch national championships. This, of course, prompted widespread imitation. Yet, far from admiration, sansho-yoke (and other defensive, time-wasting strategies) drew criticism as inherently cowardly and weak-spirited. The over-reliance on defence, waiting endlessly for opponents’ mistakes, made matches tediously long, eroding the spirit of budo. Nowadays, shinpan swiftly clamp down on such defensive postures, penalising them like vigilant gardeners pruning stray branches. They do so with a quiet resolve, knowing that each correction keeps kendo’s spirit healthy and flourishing.

Of course, this fundamental balance of ken-tai itchi extends beyond kendo into other budo arts. In karate, it is seen in the principle of simultaneously blocking with one limb while counterattacking with another; in aikido, practitioners fluidly redirect attacks, blending offence and defence harmoniously. But, just like kendo competitions, other budo are also grappling (pun intended) with the problem of overt defensiveness and passivity in competition. Judo, for instance, has its own sharp remedy: referees swiftly issue a shido (warning) to competitors who stall, evade action, or adopt overly defensive postures or grips thereby nudging them firmly back into spirited, purposeful combat. The rules keep changing so it’s hard to keep up, but my understanding is that 3 shido will result in the match being awarded to the opponent. The following video by the IJF is well worth a watch.

At the end of the day, like all budo teachings, ken-tai itchi isn’t just about martial skill; it’s about learning to spot opportunity in adversity, turning risk into advantage. Life, just like budo, inevitably brings moments of danger or difficulty, but rather than shrink from them, ken-tai itchi teaches us to harness them, shifting threats into openings. Every attack quietly prepares your defence, and every defence secretly sets up your next strike. The trick is knowing that trouble often arrives hand-in-hand with opportunity, and ken-tai itchi gives you the sense to see it coming. It’s about always being ready.

[1] Kenpō Kisoku Sūyō contained in Abe Mamoru, Kaden Kendō no Gokui (Tsuchiya Shoten, 1965) p. 174

[2] Alexander Bennett, Complete Musashi: The Book of Five Rings and Other Works (Tuttle, 2019) p. 109

[3] 懸るとも心に油断なかるべし 懸に待あり 待に懸あり(Kakaru tomo kokoro ni yudan nakaru beshi. Ken ni tai ari, tai ni ken ari.) in Ozeki Norimasa, Kendō Yōran (Dai Nippon Butokukai Yamagata-ken Shibu, 1910) p. 32.

[4] Contained in Imamura Yoshio et al (eds.) Nihon Budō Zenshū Vol. 1 (Jinbutsu Ōraisha, 1966) p. 59

[5] Contained in Abe Mamoru, Op. Cit, p. 174

No comments yet.