Budo Beat 25: Sacred Space

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

Today, I was invited to a dojo opening in Ogikubo, Tokyo, by Inoue Kazuhide-sensei. The dojo itself was stunningly beautiful, built without sparing any expense on materials and accoutrements. The opening Shinto ceremony and celebratory demonstrations got me thinking again about how truly sacred the dojo space is.

Walk into a modern dojo, and chances are you’ll see shiny wooden floors, neat rows of equipment, and earnest-looking folks clad in white or blue. Some will be swinging bamboo swords with gusto, others bowing politely enough to appease even the most finicky etiquette consultant. It might seem a straightforward scene, but there’s far more bubbling under the polished surface. In fact, calling it a room with a nice floor and a pleasant echo is a bit like describing the Vatican as a church with decent ceiling art.

Floorboards destined to be stained with the blood, sweat and tears of generations to come.

Originally, “dojo” was a Buddhist word, meaning a spot where monks trod the holy path, sharpened their spiritual wits, and spread wisdom far and wide. Over time, someone sensible decided the term fit martial arts training halls rather nicely too. In particular, kendo borrowed the term, not because practitioners fancied themselves as monks—though some certainly take austerity to a monastic extreme—but because the word captured the deeper, intangible aspects of training.

Of course, many might assume a dojo is simply where you wave weapons around and make fearsome noises, preferably without chopping off anything vital. On the surface, that’s not entirely wrong. The technical side is indeed significant; budo techniques demand meticulous precision. But to assume that’s the whole show is like going to Shakespeare for sword fights alone—there’s always something profound lurking in the subtext.

The opening ceremony was well attended, marked by dignified Shinto rituals and a deep sense of reverence for the space.

The heart of the dojo, according to tradition, is a sacred space for cultivating character and spirit, not just honing flashy skills. It’s supposed to shape inner strength, sharpen mental clarity, and bolster courage. Practicing in the dojo isn’t merely about becoming adept at hitting others, entertaining though that might be. The core business is refining oneself. That is, developing composure, sincerity, and a disciplined mind. It’s more “Zen with a sword” than just swords and shouting.

Take posture, for instance. The instruction to enter the dojo with a straight back and clear heart isn’t just old-fashioned fussiness or pedantry. The poem neatly puts it:

“When entering the dojo, straighten your body and let the mirror of your heart be free from cloud.”[1]

A neat, poetic way of saying, “Sort yourself out before stepping inside.” No slouching, physically or mentally. This isn’t merely vanity or martial arts snobbery; the logic runs deeper. A clear, calm mind is essential, and physical discipline encourages mental clarity. It’s much harder to fret about unpaid bills or unruly teenagers if you’re busy standing properly and not looking like a half-opened pocket knife.

This principle extends to attitude. You aren’t meant to carry negativity or ill intent into the dojo, nor petty jealousies or idle distractions. “Keep the mirror clean” isn’t just symbolic fluff. It’s an imperative: tidy up your mental clutter before it gets in the way. Entering with improper focus is as useful as wearing muddy boots into a posh ballroom; you can do it, but it doesn’t win friends, and you’ll soon be politely, but firmly, corrected.

Historically, this expectation stems from understanding the dojo as a sacred zone. There’s yet another a neat poetic couplet that expresses it beautifully:

“The dojo is the dwelling place of the gods. Enter and leave with reverence, and let your body vanish like foam upon the sea.”[2]

“The dwelling place of gods…” Hmmm. Sounds dramatic until you consider how often beginners mistake the instructor for a deity (or occasionally the devil). But seriously, this reverence underscores the idea of respect and humility being essential. Bowing isn’t empty ritual; it’s a gesture that confirms you appreciate being part of something larger, more profound, and far older than your latest training uniform.

In days gone by, the sacred nature of the dojo was never questioned. Everyone knew it wasn’t just a gymnasium for martial exercises. But now, in a welcome age of openness, many budo disciplines are widely regarded as sports. Yes, I know many will take umbrage at this estimation. I have more articles coming on this very topic later on. In any case, does this make budo more accessible? Definitely. Less intimidating? Perhaps. But this shift hasn’t come without its pitfalls. As the boundaries blur, the notion of a dojo being genuinely sacred grows fuzzy around the edges.

Of course, any festive occasion in kendo starts with a demonstration of the Nihon Kendo Kata.

Too often, casual attitudes seep into places meant to embody seriousness and respect. It’s all too easy these days to stroll casually onto the polished floor as if wandering into your local café for a spot of brunch. Proper etiquette can easily be cast aside when you become overly familiar. Respect diminishes, rituals become perfunctory, and the place risks becoming little more than a hall for exercise. This isn’t to say exercise halls are bad—heaven forbid—but a dojo stripped of respect is akin to reading Hamlet as a bedtime story: you miss something vital.

Respect is more than a set of formalities. It anchors human relationships. The dojo is dedicated not just to skill, but also to fostering human dignity and mutual regard. It isn’t simply good manners; it’s essential to the very fabric of what makes a dojo meaningful. Lose this, and the dojo itself loses its soul, becoming just another hall rented by the hour.

Another poetic line captures this perfectly:

“The dojo is the path where body, mind, and skill unite; neglect it not, for here we forge ourselves as better people.”[3]

The word “forge” isn’t chosen lightly. Anyone who has suffered through rigorous training knows it’s less gentle polishing and more red-hot hammering. You don’t always leave feeling refreshed or cheerful. Sometimes, you stagger out wondering if you could have picked an easier hobby, like stamp collecting or competitive knitting. But that forging is vital. It molds character, refines discipline, and shapes a more robust, thoughtful person.

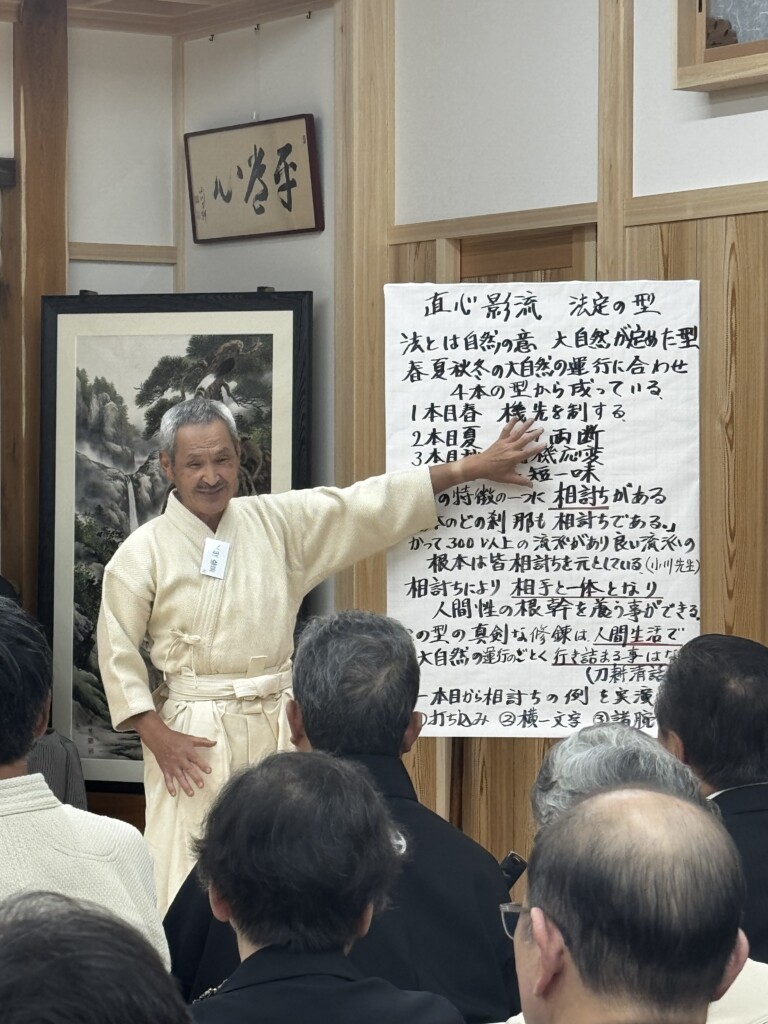

Kato-sensei gave a powerful explanation of the significance behind the Hōjō no kata before demonstrating the renowned techniques of Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryū. Having studied this school for nearly 20 years, I found the emphasis on ai-uchi especially moving.

So perhaps a dojo should be viewed as something between a church and a forge, minus the bellows and the uncomfortable pews. It’s a space for purposeful discomfort, self-examination, and genuine growth. Everyone who steps in—beginner or veteran—should do so with respect, recognizing they’re part of something larger. Casual approaches may work fine for a yoga class in a strip mall. But in the dojo, you must at least pretend you care about the deeper meaning until, gradually, you find that you genuinely do.

To maintain this clarity of purpose, the challenge now is resisting a drift toward casual convenience without sliding into rigid formality. Balance is crucial. Too loose, and the essence fades; too tight, and the joy evaporates. It’s a tricky equilibrium, but it matters. Done right, a dojo remains not just a place for physical practice, but a realm of character development, humility, and personal growth.

Thus, as I make my trip home to Kyoto on the Shinkansen, I reflect on how the dojo isn’t merely a space for budo; it’s a crucible for making humans better. Keeping this idea alive requires effort, understanding, and perhaps occasional reminders delivered firmly yet politely. Congratulations Inoue-sensei for your beautiful dojo.

[1] Kinoshita Jutoku, Kenpō Shigoku Shōden, (Budō Shōreikai, 1913) p. 51

[2] Abe Mamoru,Kaden Kendō no Gokui, (Tsuchiya Shoten, 1965) p. 34

[3] Ibid.

No comments yet.