Budo Beat 26: The Philosophy of Zanshin No. 3 – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 2)

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The following is a [rough] translation of No.3 of my 25-article series titled “The Philosophy of Zanshin” (残心の哲学) published in Japanese in the Nippon Budokan’s monthly magazine, Gekkan Budo (“Budo Monthly”, March 2023, pp. 36-41). It’s a rough translation, but I hope it offers some insight. You can read the previous articles at the following links:

No 1. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The Essence of Budo”

No 2. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin (Part 1)”

Introduction

As introduced in my previous article in this series, the term zanshin first appeared in a handful of martial arts manuals from the early Tokugawa period (1603-1868). Its meaning varied somewhat depending on the era and martial arts school. With the modernisation and competitive transformation of martial arts, zanshin has become established as a central concept. This article focuses specifically on swordsmanship. I examine how zanshin became established in the lexicon of modern budo through addressing the frowned-upon act of “hikiage”—the premature relaxation or haughty withdrawal to assert victory following the completion of a technique in a match.

Development of Gekken (Fencing with Protective Equipment)

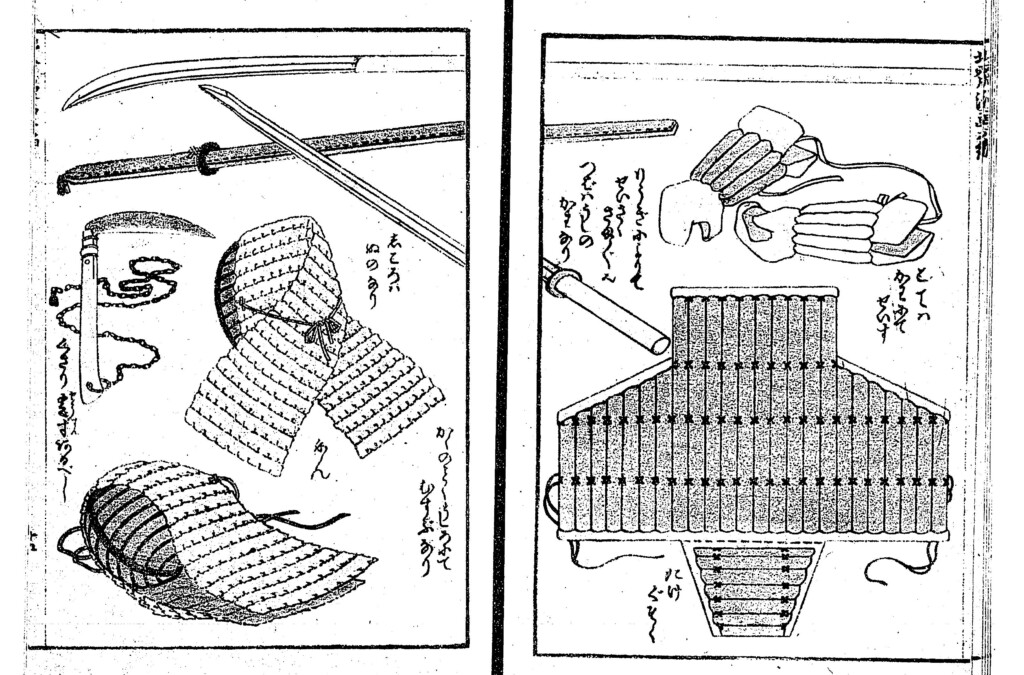

From the early 18th century, protective equipment for swordsmanship was developed by schools such as Jikishinkage-ryū and Ittō-ryū, allowing practitioners to safely test their techniques through realistic exchanges. This innovation arose during a peaceful era, a time when martial arts schools (ryūha) rapidly proliferated. However, as the number of schools grew, many critics argued that the kata forms practiced by newer ryūha had become overly exaggerated, ostentatious, and disconnected from practical combat effectiveness.

The introduction of armour designed for full-contact training (uchikomi keiko-hō) and bamboo practice swords (shinai) was a direct reaction against these excessively stylised and ornamental practices, derogatively known as “kahō kenpō” (flowery swordplay). Throughout the 18th century, the more practical and dynamic approach using armour and shinai gained popularity among both samurai and townsmen. This innovation enabled non-lethal competitive matches between swordsmen from various traditions, marking the beginning of a sporting form of swordsmanship known as gekken—literally, “clashing swords.”

As gekken-styled kenjutsu spread across various feudal domains, private dojos flourished nationwide. Particularly in Edo, three prominent dojos emerged—Saitō Yakurō’s Renpeikan (Shindō Munen-ryū), Momonoi Shunzō’s Shigakkan (Kyōshin Meichi-ryū), and Chiba Shūsaku’s Genbukan (Hokushin Ittō-ryū)—collectively known as the “Three Great Dojos of Edo.” These institutions significantly influenced the technical and philosophical foundations of modern kendo.

Among the various teachings of Chiba Shūsaku’s Hokushin Ittō-ryū, the concept of zanshin was particularly emphasised. For example, the text Hokushin Ittō-ryū Jūnikajō Eki contains the following explanation:

“Zanshin means striking without any hesitation left in your mind. Deliberately striking at a place you do not believe you can hit is itself an expression of zanshin. Striking wholeheartedly, abandoning concern for self-preservation, aligns with the true principle. It may seem reckless to do so, but failing to push oneself into such danger results in doubt and hesitation. Such a fearful mindset prevents one from achieving technical mastery and spiritual refinement. Thus, in every victory lies the seed of defeat. […] This is the essence of the profound swordsmanship of ‘ittō enman’ in which a single strike embodies perfect unity of mind, body, and spirit.”[1]

In other words, regardless of the outcome, if an attack is not executed with total conviction of mind and body, one forfeits opportunities for victory and cannot achieve the highest principle of swordsmanship. Therefore, the zanshin described here focuses not merely on maintaining vigilance after striking, but more crucially on mental resolve and total commitment before and during the strike itself.

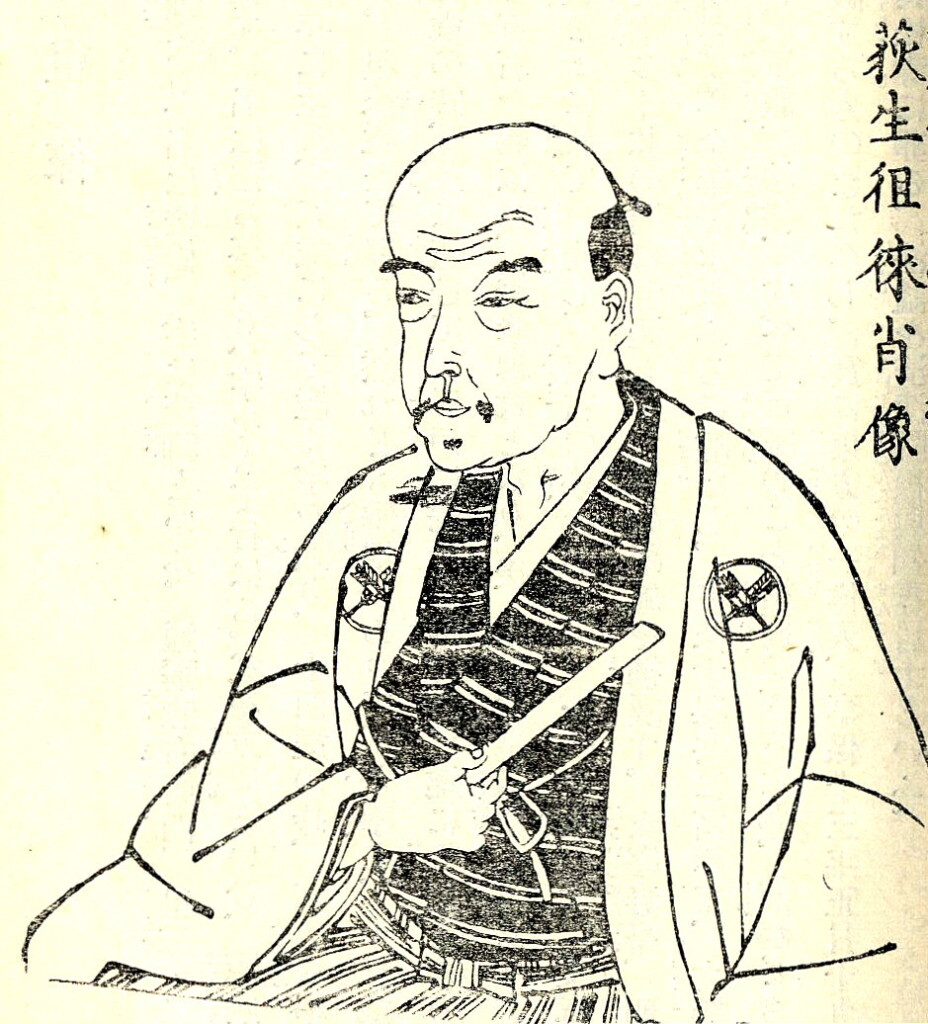

However, from its inception, sparring matches with bamboo swords brought with it new issues. An intriguing passage appears in Ogyū Sorai’s Kenroku (1727):

“In these times, both spear and sword arts are largely devised by those who have known only peace. Matches usually involve facing off against a single opponent, surrounded by numerous spectators, with primary emphasis placed on winning elegantly and impressively. Moreover, as society has grown ever more refined and even samurai accustomed to comfort, practitioners now prefer to debate lofty theories, emphasise graceful movements and impressive forms, and employ protective equipment to ensure that blows from bamboo swords cause no pain. They polish dojo floors with peach kernel oil to prevent slipping, wear leather tabi to avoid falling, or perform techniques in formal attire. Although practitioners consider such practices the pinnacle of sophistication, these methods are utterly useless on the battlefield. Martial arts should fundamentally involve conditioning one’s body for swift and agile movement. Yet dismissing practical skills as crude and focusing instead on theoretical elegance renders such martial arts little more than frivolous entertainment for peaceful times.”[2]

A cutting appraisal indeed. In other words, swordsmanship (and similarly spear-fighting) at the time was criticised as having been developed primarily by people who had never experienced real combat and was thereby overly focused on impressing audiences with dramatic techniques and spectacular victories. Many so-called ‘experts’ in this era who made their living teaching martial arts were criticised as being essentially frauds. Sorai proffers, rather cynically, that swordsmanship practised in this manner was merely a farce of peaceful times, dominated by theoretical discourse rather than genuine combat skills.

This commentary was written during the early development of gekken. Particularly notable is the growing emphasis placed on victory as gekken became more widespread, along with the considerable satisfaction practitioners derived from winning—an attitude strikingly similar to that of modern athletes. By the 1800s, swordsmen who demonstrated their prowess not on battlefields but on dojo floors had become genuine celebrities, their fame echoing throughout the country. Rivalries were fierce, and it is clear that the much-maligned “win-at-all-costs” mentality to the detriment of tradition in today’s budo is by no means a recent phenomenon.

By the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods, a behaviour known as hikiage started to emerge in sparring matches. Hikiage involved failing to maintain zanshin—the essential state of continued alertness—after successfully striking an opponent. Instead, combatants would run past their adversaries, abruptly break off engagement, or strike theatrical victory poses. At a time when standardised rules did not yet exist and bouts were often judged by the competitors themselves, these acts served as blatant displays of dominance, with fighters openly boasting, as if to say “How’s that? Had enough yet?”

Although initially tolerated, such behaviour gradually became exaggerated and excessive, particularly during popular gekken kōgyō fencing demonstrations that emerged as public entertainment in the early Meiji era. As noted in the Nisshin Shinjishi (Issue 43, 1873), these “gekken meetings and jūjutsu tournaments began to resemble theatrical Kabuki performances.” Consequently, flamboyant displays of superiority, epitomised by hikiage, drew widespread criticism in contemporary media as being undignified. From this, the term zanshin gradually began to be used as an admonition against arrogant behaviour. Hikiage was considered disgraceful because it revealed not only conceit, but also a blatant disregard of vigilance.

“Hikiage without Zanshin”

According to Nawata Tadao’s Kendō no Riron to Jissai (1940), the origins of hikiage can be traced back to the prolonged peace of the Tokugawa shogunate years. “Specifically, the Bunka-Bunsei period (1804–1830), when samurai morality had seriously deteriorated. Due to the long-standing peace, martial arts became decorative performances divorced from actual combat, leading practitioners to adopt the habit of hikiage during matches” (p.129). Furthermore, it is explained that practitioners withdraw and stop to emphasise victory under the following circumstances: ① when they are certain they have scored a decisive strike; ② when they are pressured by an opponent’s relentless attacks, leaving no room to counterattack; and ③ when their strike is uncertain, but they wish to create the appearance of victory. However, all of these situations, according to Nawata, “reflected an inappropriate attitude, condescension and have been rejected as acts of cowardice.”

From the late Meiji period (1868–1912) onward, budo gradually became integrated into Japan’s education system and quickly spread among the general public. In the 1936 publication Kendō Kaisetsu by the Kendō Education Research Association, the authors express regret that by the end of the Taishō era (early 1920s), hikiage had become commonplace. They highlight clearly how problematic breaches of etiquette had grown increasingly frequent and unchecked within the kendo community (p. 56).

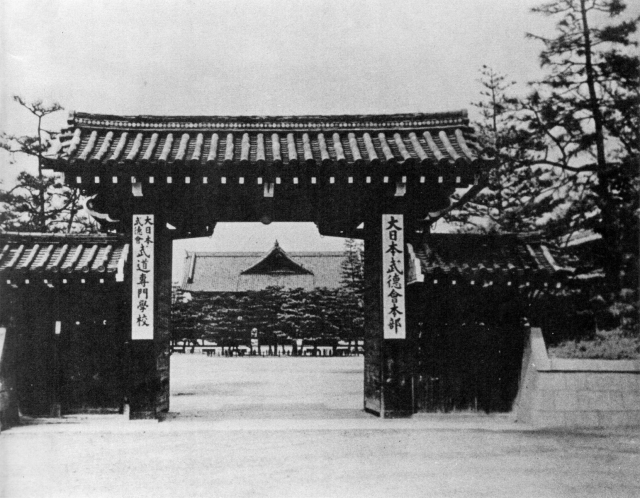

To address this issue, the Dai-Nippon Butokukai (Greater Japan Society of Martial Virtue), founded in 1895 to promote and uphold budo culture, took early steps to eliminate such problematic behaviour. In their 1907 publication Kenjutsu Kōshū Kitei (Regulations for Swordsmanship Instruction), they explicitly stated:

“During a match, if practitioners shout triumphantly and withdraw carelessly after believing they have successfully landed a strike or thrust, it demonstrates a failure to maintain vigilance against potential counterattacks. Traditionally, this has been emphasised in teachings about zanshin (lingering alertness), and practitioners are urged to exercise utmost caution. However, recently it has become increasingly common for competitors to turn their backs when retreating—a habit both exceedingly careless and dangerous.”

Thus, the Butokukai explicitly stated that techniques performed with this kind of negligent behaviour would not be considered valid, actively attempting to stamp out the issue at an early stage.[3] In spite of their efforts, the practice of hikiage became habitual among the new generation of kendo practitioners. In Kendō no Shintei (1923), Hori Shōhei argues that hikiage does not merely indicate an absence of zanshin, but also reveals fundamental defects in a practitioner’s character:

“Some practitioners, upon delivering a successful strike, grow overly pleased with themselves and leisurely glance around the room; others, when struck by an opponent, anxiously scan the faces of spectators for approval. Such behaviours usually stem from a lack of seriousness and insufficient zanshin—the alert, composed mindset described in the proverb, ‘After victory, tighten your helmet cords until you’ve captured the enemy’s stronghold.’ Another underlying cause for such conduct is a deficiency in personal character.” (p. 25)

Similarly, Ogawa Kinnosuke, a renowned figure in kendo during the Shōwa era (1926-89), bemoaned this tendency in his Kaitei Teikoku Kendō Kyōhon (1937):

“One such instance occurs when practitioners disguise their own inadequacy—having exhausted their technique and spirit—with the graceful-sounding pretext of smug withdrawal (hikiage), concealing their weakness behind an elegant façade. This is a cowardly act, akin to deliberately forcing a draw in judo.”[4]

In its effort to eradicate hikiage in matches, the Butokukai revised its kendo competition rules in 1927, clearly declaring its intent to strictly enforce penalties for breaches of etiquette:

“Article 6: Hikiage is prohibited. Violators will first receive a warning from the referee; if the violation continues, the match will be halted. (Note: Here, ‘hikiage’ refers to actions which, regardless of whether an effective strike was made or not, involve dropping one’s guard, relaxing concentration, and interrupting the match. It does not include cases where zanshin is maintained following a strike.)

Article 7: If, after delivering a strike, a competitor relaxes their concentration and demonstrates a lack of zanshin, subsequently receiving a counter-strike, the competitor executing the second strike shall be declared the winner.”[5]

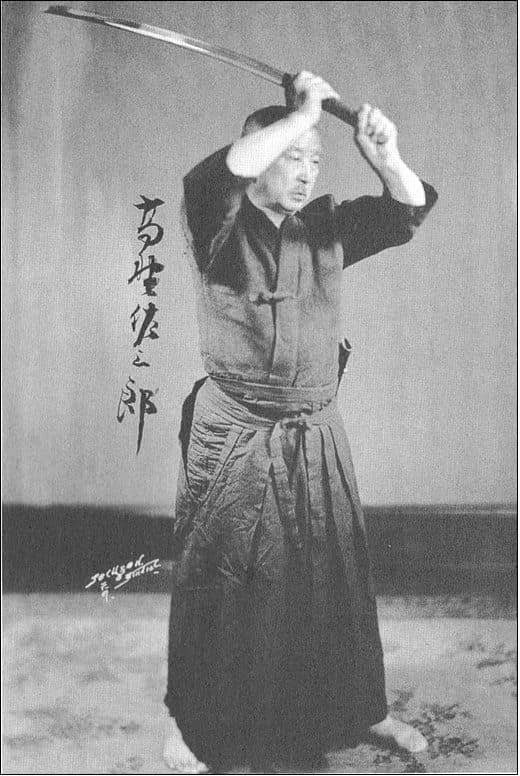

By the Taishō era (1912–1926), instructional texts for kendo kata regularly emphasised zanshin as a critical component for properly concluding each form. The introduction of explicit references to zanshin within competition rules specifically highlighted an intense aversion by the powers that be to the persistence of hikiage. Furthermore, kendo textbooks began providing increasingly detailed explanations of zanshin. Particularly influential were the two definitions articulated by Takano Sasaburō, a key figure in the development of modern kendo. His interpretations significantly shaped kendo as well as other forms of budo, both directly and indirectly.

“The first meaning — Zanshin refers to not letting your guard down, even after successfully striking your opponent. It means maintaining vigilance and staying mentally connected to the opponent, ready to respond immediately if they attempt another technique. Thus, after delivering a strike or thrust, you must retain a state of constant alertness.

The second meaning — Zanshin also means attacking without reservation, completely exhausting your mental and physical energies in a strike. Although this interpretation might seem contradictory to the literal meaning of the word, it essentially describes the same principle. When you attack wholeheartedly without reservation, you paradoxically achieve a state of heightened awareness. By fully committing yourself to the strike, leaving nothing in reserve, you naturally regenerate your readiness. When your sword has fulfilled its purpose, you discard attachment to that action and instinctively retain a state of alertness towards your opponent. Conversely, intentionally trying to ‘retain’ awareness leads to hesitation, creating openings. If any doubt remains when attacking, your reach is compromised, your sword lacks power, and effectiveness is diminished. You will never achieve mastery of the subtleness requiring instantaneous action. Only by attacking without reservation and consistently training in dangerous situations or from disadvantageous positions can you ultimately achieve genuine victory.”[6]

The “first meaning” described above is the interpretation of zanshin generally understood in contemporary kendo. However, the “second meaning”, while present in the earlier Hokushin Ittō-ryū explanation, seems largely forgotten today. This is perhaps because the practice of hikiage came to be regarded as so antithetical to the spirit of budo that the emphasis shifted heavily towards the first definition of zanshin as justification for criticising it. Despite being widely condemned, the practice of hikiage did not disappear. In fact, an article titled “Recommendations on Completely Eliminating Hikiage” published in the December 1941 edition of Butoku (Issue No.120) conveys a sense of despair, declaring unequivocally that “hikiage is a most deplorable act.” It explicitly places responsibility on instructors to eradicate the practice:

“Those in positions of instructional authority must thoroughly research and understand the difference between proper zanshin and the improper behaviour of hikiage, aiming to enhance their refereeing skills and ensure faultless judgment in competitions.”[7]

Moreover, the article advises that during regular training sessions, instructors should “Clearly illustrate the harmfulness of hikiage by providing examples drawn from tales of old warriors and actual experiences from contemporary warfare. They must thoroughly explain why the lack of zanshin in such actions is unbefitting a serious martial artist and diligently instruct their students accordingly.”

These admonitions also reflect the broader historical context of the time—namely, an underlying sense of urgency to ensure budo was practical and effective for battlefield application.

Post-war Kendo and Zanshin

After Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, the Butokukai was disbanded, and martial arts were prohibited for several years. In 1952, the All-Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF) was established, and kendo was reborn as a sport deemed “suitable for a democratic society”. Through the 1960s and 70s, kendo and other budo disciplines saw a complete revival, rapidly gaining popularity and leading to a significant increase in practitioners and nationwide competitions.

However, persistent problems with regards to competition etiquette and attitudes remained. Excessive competitiveness and fixation on winning were viewed as detrimental to the ideals of personal growth central to budo. Additionally, disrespectful behaviours such as hikiage without proper zanshin continued to be a frequent source of concern. From 1979, in an explanatory note accompanying revisions to its official competition rules, the AJKF clearly defined the criteria for valid strikes, emphasising the traditional importance of zanshin.

“Since ancient times, zanshin has always been central to kendo; thus, its importance within the Way (dō) is beyond question. From this perspective, valid strikes in contemporary kendo must be assessed comprehensively, including the state before, during, and after striking. Therefore, if a competitor exhibits disgraceful hikiage lacking zanshin following a strike, even if the strike had initially been declared valid, referees may, through consultation, revoke that decision.”

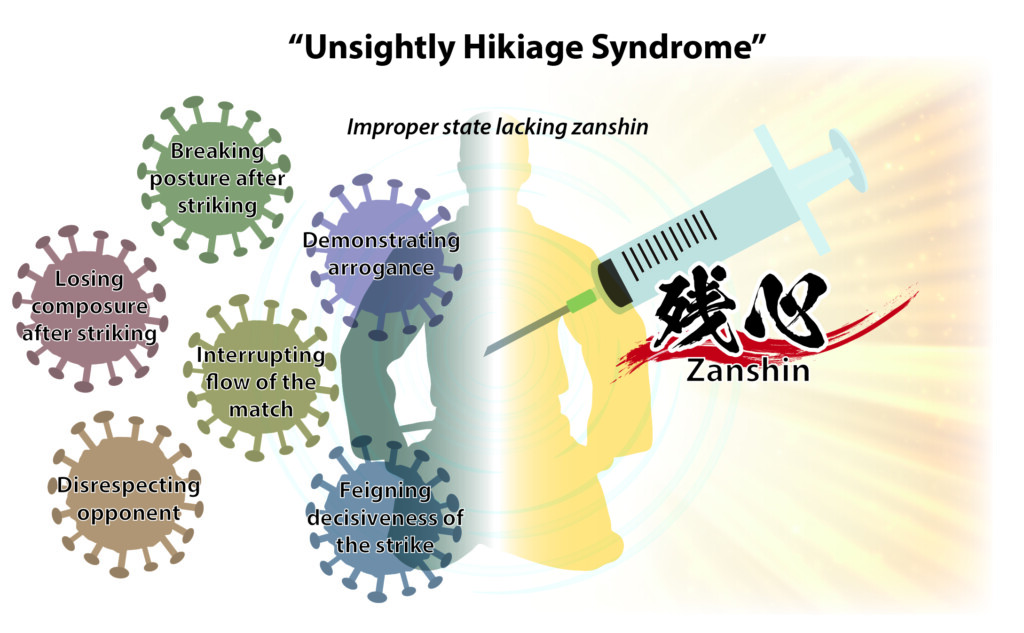

The AJKF explicitly defined improper hikiage as follows: “An illegal action that clearly lacks zanshin, such as relaxing alertness, breaking posture, or interrupting the flow of the match immediately after executing a strike.” Thus, even a strike initially declared valid could be overturned through referee consultation if accompanied by inappropriate hikiage. Moreover, such behaviour itself may be penalised as a violation even if no effective strike has occurred.[8]

Furthermore, in June 1987, the AJKF’s official bulletin (Zenkenren Kōhō, Issue No. 70, p. 8) clearly outlined the criteria for valid strikes, emphasising both correct blade trajectory (hasuji) and the presence of zanshin. Significantly, the term “hikiage” was removed altogether. From October 1988, Article 12 of the Competition and Refereeing Regulations explicitly defined a valid strike as follows:

“A yūkō-datotsu (valid strike) is defined as an accurate strike or thrust made onto designated targets (datotsu-bui) of the opponent’s kendo-gu. The strike or thrust must be executed in high spirits with correct posture, using the striking section (datotsu-bu) of the shinai with the correct angle (hasuji), and followed by zanshin.”

This marked the first instance in which zanshin was officially incorporated as an explicit requirement for determining valid strikes. This shift reflects the recognition that assessing the presence of zanshin is clearer and more understandable for referees and competitors alike than attempting to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable forms of hikiage.

Summary

In writing this article, I have reaffirmed that exploring the deeper meanings of zanshin offers valuable insights for my own training. Notably, the “second meaning” of zanshin as defined by Takano Sasaburō has largely been forgotten today. However, perhaps it is precisely through practising this second form of complete, wholehearted commitment that the more familiar first meaning—maintaining vigilance after striking—truly emerges.

I also strongly feel that the practice of hikiage continues to plague contemporary kendo (and other budo). Although we might avoid conspicuous gestures such as fist-pumping, we often unconsciously fall into the habit of subtle forms of hikiage during training, something that warrants careful reflection. Clearly, the teachings and guidance of past masters remain entirely relevant, and we must genuinely heed their advice. This act of earnest reflection, of carefully examining the wisdom of our predecessors, is precisely what “keiko”[9]—literally “thinking deeply upon ancient wisdom”—is meant to embody.

This article has specifically focused on kendo. While martial arts manuals from the Edo period occasionally referenced zanshin in disciplines such as spear fighting, archery, and jūjutsu, these mentions were rare. It is primarily through kendo (and later kyudo, albeit with slightly different nuances) that the term zanshin gained widespread recognition and eventually influenced other modern budo forms. This, in the next article, I will examine how the concept of zanshin is applied and interpreted in other contemporary budo arts.

[1] Chiba Eiichirō ed., Chiba Shūsaku Ikō, (Ōkasha, 1942)p. 137

[2] Reproduced in Watanabe Ichirō, Budō no Meicho, (Tōkyō Kopii Shuppanbu, 1979) p. 301

[3] Dai-Nippon Butokukai, Butoku-shi, Vol. 2, No. 7, July 1907, p. 80

[4] Contained in Kindai Kendō Meicho Taikei, ed. Imamura Yoshio et al. (Dōhōsha Shuppan, 1985–1986) Vol. 9, p. 31

[5] Ibid., Vol. 6, pp. 293–294

[6] Takano Sasaburō, Nihon Kendō Kyōhan, (Asano Shoten, 1920) pp. 151–152

[7] Contained in Nakamura Tamio, ed., Shiryō Kindai Kendō-shi (Shimazu Shobō, 1985) p. 261

[8] AJKF, Zenkenren Kōhō, Issue No. 30, May 1978, pp. 6–7

[9] Keiko is the term used to designate training in the context of budo.

No comments yet.