Budo Beat 48: Just Forget it! ~ A Few Thoughts on “Sambō” and “Sutemi”

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

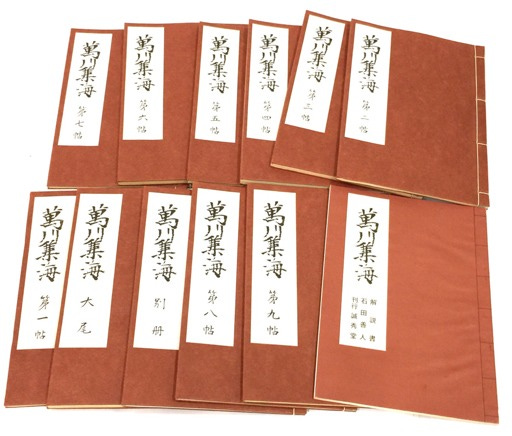

This piece began, somewhat unexpectedly, with an email from a UK publisher about a year ago asking whether I would be interested in translating the Bansenshūkai (万川集海). I’m now putting the finishing touches on the manuscript, with submission scheduled for the first week of January. Seriously, no rest for the wicked.

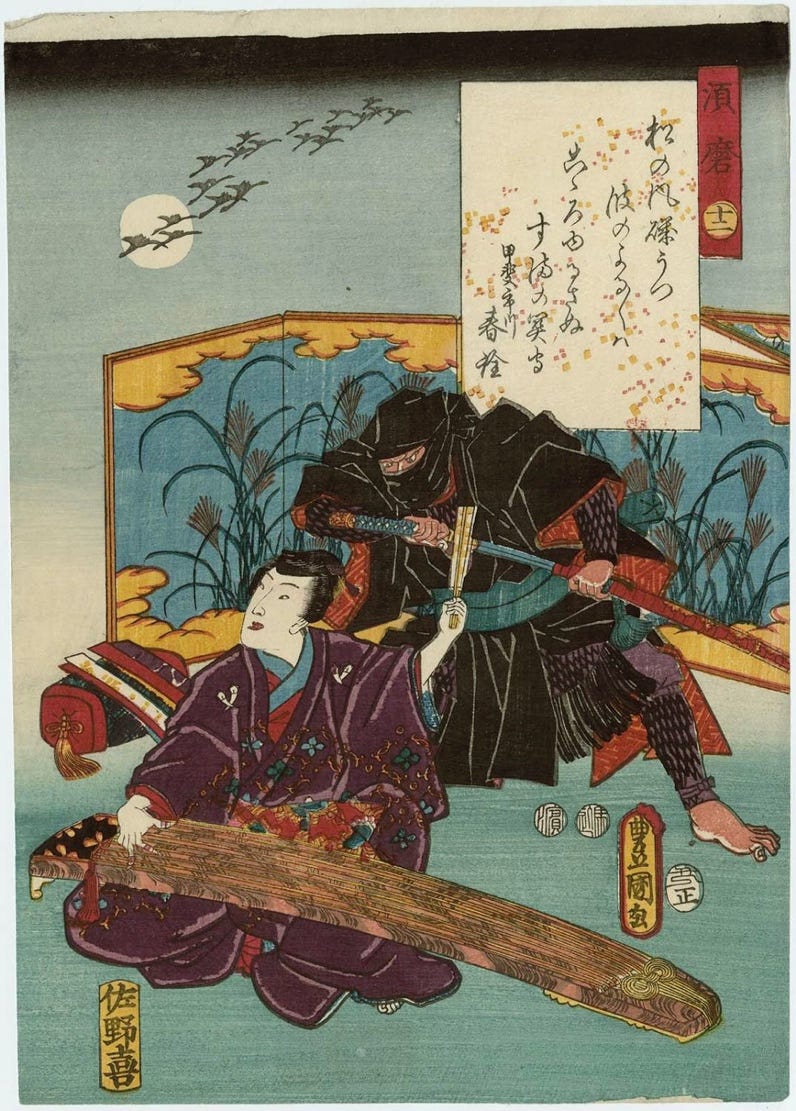

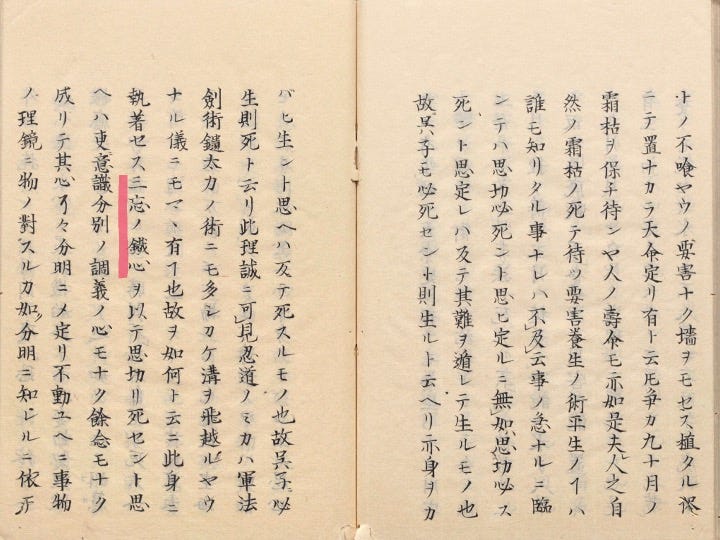

So, what is it? The Bansenshūkai is a vast seventeenth century compendium of Iga and Kōga shinobi (=ninja) knowledge, compiled by Fujibayashi Yasutake in 1676, at a time when large-scale warfare was receding and reflection had become possible. I’m basing my translation on the copy stored in the National Archives on Japan. (It is conveniently available online at this link.) It is not a how-to manual for skulduggery so much as an encyclopaedia of early modern military thought, dealing with intelligence gathering, psychology, logistics, and contingency planning. In other words, no, this is not me going over to the dark side!

Like many classical martial texts, it ultimately says far more about strategy, perception, and human weakness than it does about sneaking around in black pyjamas! Honestly, translating it has been an exercise in historical literacy rather than moral realignment, and what surprised me most during the work was not any particularly exotic technique, although there are a few neat tricks and ideas in there, but a short phrase that stopped me in my tracks because of how directly it spoke to the budo mindset: sanbō (三忘), the “Three Forgettings”. I ain’t talking about my usual three forgettings of keys, phone, and whatever it was I walked out of the house to do. And I also ain’t talking about the Russian self-defence art with basically the same name! This is a bona fide budo concept that I’d never come across before.

At first glance the words look almost banal. Three. Forget. Hardly revelatory. But the surrounding passage opens the idea out with unexpected force. Sanbō no tesshin (三忘の鉄心). A Heart of Iron forged through the Three Forgettings.

As the Bansenshūkai puts it:

“There are times when one must leap across a great ditch or vault over a high cliff. At such moments, if one abandons attachment to personal safety and, with the Iron Heart of the Three Forgettings, utterly casts aside consciousness, discrimination, and calculation, and moves with the fierce resolve to die, one enters the realm of the Three Forgettings. All stray thoughts vanish, and clarity penetrates to the furthest corners of the mind.”

The phrasing points to a mental state that most modern budoka spend time circling without ever quite naming. My initial assumption was that it was simply another variation on mushin (no mind) or a familiar sermon about detachment. It’s not quite that. Sanbō is not detachment as removal. It is detachment as preparation. A clearing away of noise so that something trained and genuine can function without interference.

The “Three Forgettings” themselves are straightforward enough to list: forget the body, forget the mind, forget the opponent. As so often in classical Japanese thought, the simplicity of the language hides a demanding discipline.

“Forgetting the body” doesn’t mean pretending it doesn’t exist. It means releasing the constant internal commentary about how you feel today, whether your knee is playing up, whether the other fella looks stronger, or whether you remembered to tape that ripped gash on your foot. Every martial artist recognises this chatter. The more closely you listen to it, the slower and more hesitant you become. Forgetting the body is not recklessness, nor is it bravado. It is the removal of the tension that comes from clinging to safety with both hands.

I got a cracked rib at jukendo training just the other day. It still hurts! The injury itself is manageable enough, but I’m finding that even the thought of it can be completely debilitating, far more than it needs to be. Pain is one thing; the mental fixation on the pain is something else entirely. This is where the boundary between body and mind starts to blur. Physical discomfort is real, but it is the mental commentary attached to it that magnifies hesitation and stalls action.

“Forgetting the mind” is thus quite tricky. Anyone who has stood waiting for a grading or an important bout knows how the mental noise really ramps up. You tell yourself not to think, and the mind obliges by thinking louder. In classical texts like the Bansenshūkai, forgetting the mind means refusing to feed this internal commentary. You let it mutter in the background while you act anyway. Over time, it quiets down. Modern practitioners talk about flow states or performance calm. Getting in the zone. The old texts were blunter. Just forget the bloody mind! Trust the training and repetition that have already done the work.

“Forgetting the opponent” sounds counterintuitive for something described as a martial principle. Surely recognising the enemy is the whole point. The confusion comes from taking “forgetting” too literally.

You don’t stop seeing the person in front of you. You still perceive distance, timing, pressure, and intent. What is forgotten is the mental picture of the opponent as a problem to be solved or a threat to be managed. Once that picture takes hold, movement tightens and becomes reactive.

Forgetting the opponent means dropping this mental framing. It is not mystical union, and it is not indifference. It is simply acting without fixating on the idea of an enemy. When that fixation falls away, action arises more naturally from the situation as a whole. Budo practitioners sometimes hint at this when talking about relational timing. When the opponent is no longer something you push against in your head, movement becomes cleaner and far less hesitant. This has been a common theme in my writing over the last year. I can’t say I totally get it yet, but slowly getting there…

When all three forgettings are forgotten, sanbō no tesshin emerges. A heart of iron. Not because it is hard, but because nothing sticks to it. No fear of pain, no babble of doubt, no fixation on winning or losing. It’s not coldness, but more absolute freedom.

The Bansenshūkai continues:

“One no longer allows oneself to be misled by surrounding circumstances; neither fear of the demons before one nor the slightest doubt clouds the heart. Returning to one’s true mind, one never loses the moment of opportunity. Body and mind both move in full accord with Principle, without effort.”

Anyone who has trained long enough has tasted this state, if only briefly. Everything aligns. You move without deliberation. By the time you consciously register the opening, your body is already acting.

For me, sanbō sits very close to another concept that circulates constantly in budo circles: sutemi (捨て身). Literally, to discard the body. In modern usage, sutemi is often taken to mean wholehearted commitment. Judoka speak of sacrifice throws. Karate practitioners use it to describe decisive attacks. In kendo, sutemi refers to the moment when you step in without holding anything back and not worrying about the result or consequences.

There is an obvious family resemblance between sutemi and the “first forgetting”. But sutemi goes further. It is not only the body that is cast aside, but the outcome as well. Sutemi is the willingness to stake everything on a single moment, without hedging. In that sense it overlaps strongly with sanbō. Once body, mind, and opponent are forgotten, what remains is simply action. Clean intent, unpolluted by second guessing.

In my experience, sutemi is less about courage than honesty. You can’t fake it. Anyone who has trained for long enough can tell the difference between a genuine sutemi strike and a theatrical imitation delivered with one foot still on the brake.

As the text puts it for sanbō, once this state is reached, action becomes effortless:

“Like a ball rolling upon a board or a gourd upon water, one responds freely to changing circumstances. Without seeking victory, one prevails; even where death should await, one slips free.”

This is precisely what underlies sutemi. When commitment is real, the fear that normally fuels hesitation evaporates. What replaces it is not relaxation in the onsen-resort sense, but a clear, almost clinical decisiveness. The Bansenshūkai section on this concept makes it clear, I think, that sanbō is not a gift bestowed by temperament. It is a forge. Forgetting is a discipline, not an act of negligence. Classical warriors were not cultivating stoic indifference. They were training to remove anything that interfered with perception and timing. In modern budo we devote enormous energy to refining technique, yet we often neglect the internal clutter that prevents technique from appearing in its natural form.

I have seen this repeatedly in gradings and competitions. Naturally, my own as well! Candidates or competitors with solid fundamentals and great technique come undone because pressure reintroduces hesitation. Their technique doesn’t vanish. Their freedom does. Conversely, a small number of individuals appear almost unconcerned by the stakes. They are not fearless. They’re unburdened. When they step in, the line of action is unmistakable. Although I have never seen the word apart from in the Bansenshūkai, sanbō lives in their movement. This has put a new perspective on something that is really holding me back at the moment. I totally get it in theory, but I haven’t yet got it… Maybe this will help.

We spend most of our training time remembering stuff. Remember the grip, the kamae, the distance, the timing. Remember what sensei said last week… Forgetting sounds somewhat counterproductive. But sanbō is not a denial of all this learning and rumination. It is the clearing of space so that learning can function. At least, that’s what I read into it.

I am finding that one of the ironies of long training is that the more knowledge we accumulate, the less we seem to trust it. The mind tries to supervise what the body already knows how to do. Then everything becomes slower and more brittle. Sanbō is the art of stepping aside and letting the training and embodied knowledge speak. The ultimate auto-pilot. In that sense, both sutemi and sanbō cut through physical hesitation and mental attachment alike. They approach the same problem from different angles, but the work they do overlaps far more than I first envisaged. It’s taken me a good six months of deep thought into the matter to come to this conclusion.

I should add, I think that there’s also a quiet ethical dimension here. Forgetting the opponent removes the projections that feed fear and arrogance. The person in front of you becomes neither “demon” nor audience, but part of the shared moment. Action becomes cleaner, less ego-driven, and paradoxically more humane.

Working through the translation of this passage felt like being handed an uninvited Zen riddle. The longer I sat with it, the more I recognised it through my decades of practice. All those injunctions to relax, commit, and trust training were variations on the same instruction. Remove what is unnecessary. Let what remains function. If only…

Sutemi and sanbō belong to the same family. Both demand honesty and strip away hesitation, not in some lofty philosophical sense, but in the very practical moment where you either move or you don’t. I see this whether you are reading an Edo-period text like the Bansenshūkai, stumbling through the controlled chaos of keiko on a Wednesday night at the Butokuden in Kyoto, or catching one of those rare moments when everything actually lines up.

What they point to is uncomfortably simple. Freedom in budo is not something we acquire by adding more spirit, intent, or clever ideas, although these are all impiortant and linked together in various ways. It appears only when we get to the point when we can stop interfering with what training has already put in place. And this leads to that old cliché. Most of the time, the real opponent is not the person in front of us, but our own refusal to let go.

Ah! That reminds me. As Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in 1874, with a concision most martial artists would do well to envy: “The chief advantage of forgetting is that you can enjoy the same good things for the first time all over again.” Another good reason to just forget it.

No comments yet.