Budo Beat 54: The Philosophy of Zanshin No. 5 – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 4)

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The following is a translation of No. 5 of my 25-article series titled “The Philosophy of Zanshin” (残心の哲学) published in Japanese in the Nippon Budokan’s monthly magazine, Gekkan Budo (“Budo Monthly”, May 2023, pp. 32-38). It’s a rough translation, but I hope it offers some insight. You can read the previous articles in this particular series at the following links:

No 1. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The Essence of Budo”

No 2. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin (Part 1)”

No. 3. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 2)

No. 4. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 3)

“The History of Zanshin” (Part 4) – Zanshin in Other Cultures

Introduction

As shown in the previous articles in this series, zanshin has continued to evolve over the centuries, becoming one of the defining principles of modern budo. It is often described as the sustained alertness that follows the execution of a technique, a state in which physical readiness and mental composure are maintained so that no opening is given and any counterattack can be met without hesitation. Yet zanshin has never been limited to mere attentiveness after the strike. It functions simultaneously as posture, awareness, ethical restraint, and judgement, compressing multiple layers of conduct into a single term.

This raises an obvious question. If zanshin arises from situations of confrontation and danger, is it really unique to Japanese budo? Or is it simply one cultural expression of a more universal human response to conflict? In Western military, police, and law-enforcement contexts, a closely related idea has gained prominence under the label situation(al) awareness (SA). At first glance, the two appear similar enough to be treated as equivalents, and zanshin is increasingly translated as “awareness” or “situational awareness” in English-language explanations of Japanese martial arts.

The purpose of this article is not to argue for cultural exceptionalism, nor to deny the existence of comparable attitudes in other martial traditions. Rather, it is to take a look how different cultures have articulated the problem of sustained awareness in combat.

The Idea of Zanshin in Non-Japanese Martial Traditions

From ancient warfare to modern conflict, human beings have repeatedly engaged in armed violence for reasons ranging from territorial disputes and ideological differences to competition over resources. Despite advances in science, technology, and diplomacy, war continues to occur across the globe, leaving devastation on all sides. The persistence of conflict throughout human history serves as a reminder of the innate aggressiveness and complexity of human nature. Viewed from this perspective, it seems reasonable to regard a concept such as zanshin, which arises directly from situations of confrontation, as something essentially universal rather than culturally exceptional to Japan.

Is zanshin, then, truly a concept unique to Japanese budo? The term is often rendered in English as “lingering mind”, “remaining heart”, “follow-through”, or “awareness” “continued vigilance” etc. Yet none of these expressions adequately captures the depth and range of nuance contained in the Japanese word. There is, quite simply, no single English term that fully encompasses what zanshin implies in the context of what I have explained in my articles to date.

If we look elsewhere in Asia, close parallels can be found. In the competition rules for kendo (kumdo) in Korea, the definition of a valid strike is almost identical to that used by the All-Japan Kendo Federation. Article 12 states that a valid strike is one executed with full vigour and correct posture, accurately striking the designated target with the correct part of the bamboo sword (jukto) along the correct blade angle, and “accompanied by sonsim. (存心 J: Zonshin)”. Here, the term sonsim is used in place of zanshin. The kanji used is also different (残心 vs. 存心 Sonsim is defined as “maintaining one’s true mind firmly within the heart; its opposite is bangsim (carelessness or inattentiveness).”[1] It essentially translates as “keeping the mind present”.

The term sonsim is most often used in a Confucian context, where it carries the meaning of “keeping something firmly in mind”. Although the nuance is slightly different in China, it appears in a wide range of situations, including work, human relationships, and personal development. The idea that having a clear intention serves as a guide for action and decision-making can be said to resemble the concept of zanshin. However, sonsim did not originally emerge from a martial context. Moreover, in Chinese martial arts, the term zanshin is not used at all. In China, practitioners familiar with Japanese budo generally understand the meaning of zanshin, but when viewed purely at the level of written characters, the term is more likely to be interpreted as carrying connotations closer to “cruelty”.

Although martial cultures throughout the world share an awareness of the danger of carelessness, it is difficult to find a concept as concise and all-encompassing as zanshin. Even when historical sources are extensively compared and examined, only vague or indirect equivalents tend to emerge.

Since the 1990s, Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) have enjoyed considerable popularity in Europe and North America. HEMA refers to the reconstruction of martial systems developed in Europe from the medieval to the early modern period, including swordsmanship, dagger fighting, spear fighting, and axe combat and other arms. Using replica weapons and armour, practitioners participate in competitions and large-scale international events that recreate famous historical battles. Drawing on medieval fight books and other historical sources, enthusiasts study bodily movement and weapons techniques in order to test their skill. Whereas fencing is practised as a sport, HEMA places its emphasis on the practical application of historical combat techniques.

Does HEMA possess a concept comparable to zanshin? To explore this question, I asked a Belgian kendo colleague, Dr. Sergio Boffa, Director of the Municipal Museum of Nivelles. Dr. Boffa is a leading authority on medieval European warfare and has analysed hundreds of historical fencing manuals. According to him, “As far as I am aware, there is nothing in Europe equivalent to zanshin as it is understood in Japanese budo. In medieval and early modern sources, there is very little discussion of the psychological aspects of combat.” It is true that European martial texts frequently include phrases along the lines of “With the help of God, it will not fail”, but the cultivation of mental discipline in the sense of the shinpō-ron influenced by Zen in Japan may not have been treated as a particular priority.

There are, of course, a few exceptions, albeit rare. The Nicolas Pol Hausbuch (MS 3227a, above grpahic), a German book now held in Nuremberg, was likely compiled in the late 14th or early 15th century and contains a mix of practical and esoteric material, including fencing. Although it is often wrongly attributed to Hans Döbringer, only a short addendum reflects his work; the rest of the fencing material is anonymous and attributed to the so-called Pseudo-Döbringer, who explains and expands upon the teachings of the sword master Johannes Liechtenauer.

Within this text are some short passage in the form of verse outlining the mental attitude required to prevail in a duel:

In earnest or in play,

Have a joyous spirit, but in moderation

So that you may pay attention

And perform with a good spirit

Whatever you shall do

And whip up against him.

Because a good spirit with force

Makes your resistance dauntless.

Thereafter, conduct yourself so that

You give no advantage with anything.

Avoid imprudence.

Don’t engage four or six

With your overconfidence.

Be modest, that is good for you.[2]

This example can be said to point towards a zanshin-like mental attitude. The passage emphasises a balance between elevated spirit and restraint, insisting that vitality must be held in check so attention is never lost. This sustained attentiveness rejects overconfidence and imprudence, warning that the moment one assumes advantage, awareness collapses and openings are created. Likewise, in the writings of the fifteenth-century Italian fencing master Philippo di Vadi Pisano, in his treatise De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi (On the Art of Fighting with Swords), there is no explicit term that directly denotes zanshin. Nevertheless, expressions corresponding to what might be understood as bearing and dignity, concepts closely aligned with zanshin, do appear.

One such expression is per questa fiada, meaning “just this once”. In essence, it conveys the intention: “I could kill you, but just this once I’ll disarm you instead”. [3] It indicates the composure and latitude to show mercy towards an opponent once the contest has already been decided. In this respect, it brings to my mind the concluding movement of the third tachi form in the Nihon Kendo Kata. (See video below).

There is also an intriguing source, among many, that condemns unsportsmanlike conduct in fencing competitions, which is similar to the issue of hikiage (withdrawal) discussed in my previous article in this series. A fencing manual published in Spain in 1881 admonishes practitioners to acknowledge decisive blows received from an opponent.

All thrusts that are received must be acknowledged, the left hand being carried to the chest with frankness and sincerity, and not with shame. One must concede not only those which have in fact taken effect, but also those which, in all honesty of conscience, would not have been parried had it not been through mere accident, even though they may technically have been stopped… If one happens to fence with a person who is accustomed to refuse acknowledgment of the thrusts he receives—a practice already highly reprehensible—it would be still more so to demand them by saying, ‘You are hit’. One must therefore never ask for them; and even if the opponent fails to grant them, or positively denies them, one should nevertheless always mark those received by oneself, without delivering an attack at the same moment as one is marking, but only after the marking has been properly completed...[4]

In other words, even if one’s opponent acts deceptively, being struck should be acknowledged openly and defeat accepted without evasion. In budo arts, this attitude is encapsulated in the common budo expression “mairimashita” (maitta). The author stresses the importance of such fencing etiquette, urging constant care on the grounds that one’s attitude is regarded as a reflection of one’s character. This recalls the oft-cited ideal in kendo of “reflecting when you strike, and giving thanks when you are struck” (Utte hansei, utarete kansha).

Thus, while closer examination reveals loose points of overlap, the multifaceted structure implied by the single term zanshin, and its applicability across many dimensions of combat, appears to be genuinely distinctive within Japanese budo. That said, in recent years a term in Western contexts has increasingly been treated as equivalent to zanshin. This is the concept known as situational awareness (SA).

Situational Awareness and Zanshin

Situation(al) awareness (SA) refers to the ability to perceive and understand what is happening in one’s surrounding environment, to grasp the overall situation, and to make appropriate decisions based on that understanding. By recognising one’s environment, including potential threats and hazards, and anticipating events that may occur in the near future, SA is regarded as essential in a wide range of contexts, including aviation, military operations, emergency response, and everyday life. It is a skill that can be developed through training and experience, helping individuals to make better judgements, avoid accidents, and respond more effectively to unforeseen situations. For this reason, SA is frequently cited as a foundation for effective decision-making not only in military and martial contexts, but also in the world of business.

When did the term situational awareness come into use? Some sources suggest that SA developed alongside the establishment of fighter aircraft tactics during the First World War, but there is no definitive consensus. Fighter pilots were often described as “knights of the air”, flying above the battlefield below, an image that evoked romantic notions of chivalry and honour. Pilots who became aces were celebrated as national heroes and pressed into service for propaganda purposes. Yet behind this glamorous image lay a far harsher reality: the average life expectancy of a fighter pilot was extremely short. Across all aerial conflicts from the First World War to the present day, a very small number of pilots have accounted for a disproportionate number of victories. As one study notes, roughly five per cent of fighter pilots, the aces, have historically accounted for around 40 per cent of all victories, achieved at the expense of less talented pilots.[5]

What, then, distinguished an ace? Was it simply superior aircraft, exceptional marksmanship, outstanding leadership, or better training? Or was it nothing more than good fortune? Luck was certainly a critical factor but as Spick states, “Determination is an essential part of the make-up of a successful fighter pilot, without which he is unable to function effectively. Many fighter aces have been described as fearless; this is simply not true. What they have to do is to control their fear, which demands a high degree of determination.” Of the physical qualities required, he states “good distance vision and good co-ordination” are also essential.[6] In The Ace Factor, Mike Spick argues that there was something additional that set outstanding pilots apart from their peers, and he identifies this as situational awareness (SA).

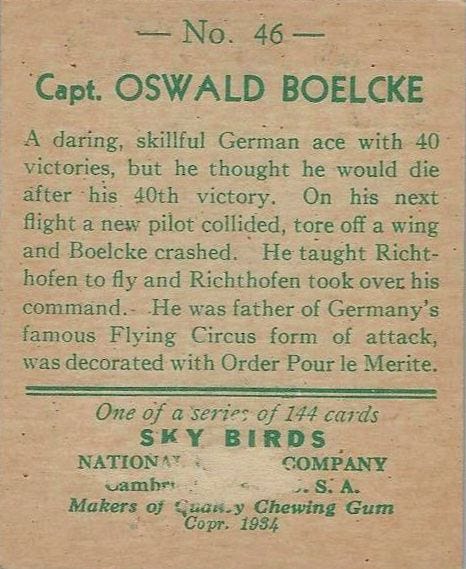

Among the pilots who rose to fame during the First World War, perhaps the most renowned is the German aviator Oswald Boelcke. With forty confirmed victories, Boelcke is often described as “the father of the German fighter arm”, and even as the father of aerial combat itself. In 1915, the very first year of organised air combat, he was already a highly influential leader and tactician. Yet in 1916, after returning from a sortie in a damaged aircraft, he died from a fractured skull because he had not fastened his helmet or safety belt.

Before his death, Boelcke formulated a set of principles and guidelines for air combat known as the “Dicta Boelcke”. These principles played a crucial role in shaping aerial tactics and strategy during the war and continue to be studied and applied by military pilots and aviation enthusiasts today. Many German ace pilots, including Manfred von Richthofen, known as the “Red Baron” and later immortalised in film, are said to have owed much of their success to the principles set out in the Dicta Boelcke. Although the Dicta do not employ the explicit term situational awareness, it is clear that the concept of SA underpins them. The principles are as follows (the comments in parentheses are my own).[7]

1. Try to secure advantages before attacking. If possible, keep the sun behind you. (Reduce the enemy’s situational awareness)

2. Always carry through an attack when you have started. (Attack with total commitment)

3. Fire only at close range and only when your opponent is properly in your sights. (Close the distance)

4. Always keep your eye on your opponent and never let yourself be deceived by ruses. (Do not let your guard down)

5. In any form of attack, it is essential to assail your opponent. (Recognise the moment to strike)

6. If your opponent dives on you, do not try to evade his onslaught, but fly to meet it. (Strike with a willingness to sacrifice yourself)

7. When over the enemy’s lines never forget your own line of retreat. (Maintain constant awareness of your surroundings)

8. For the Staffel (squadron): Attack on principle in groups of four or six. When the fight breaks up into a series of single combats, take care that several do not go for one opponent. (Maintain constant awareness of your surroundings)

This list of precepts continued to be studied and applied as a foundational text for aerial combat strategy long after the First World War, and its influence on the history of air warfare has been considerable.

The term situational awareness (SA), however, came into regular use among United States Air Force fighter pilots returning from the Korean and Vietnam wars. Recognising that superior SA was a decisive factor in victory in air combat, Spick referred to it as the “ace factor”. Survival in aerial combat depends on observing an opponent’s movements and anticipating their next action a fraction of a second before the opponent can register one’s own.

Lieutenant Colonel Randy Cunningham, a Vietnam War ace pilot and apparently one of the real-life models for the film “Top Gun”, described SA in terms of “winning and surviving”. He explained that a pilot must possess three-dimensional awareness and feel time, distance, and relative motion as if they were part of his own soul. Only by sensing what is happening around the pilot take action and make the correct decisions.[8]

From the 1990s onwards, SA came to be widely used by researchers in the behavioural sciences studying human factors. In particular, Mica Endsley, an engineer and former Chief Scientist of the United States Air Force, is a leading figure in the field of situational awareness. She has authored more than 200 scientific papers and reports on SA and is widely recognised for her pioneering work using SA models in the design, development, and evaluation of systems that support human situational awareness and decision-making. Her human-centred design approach is regarded as essential for effectively integrating advanced technologies and automation with individuals across diverse domains. She has also developed training programmes aimed at improving situational awareness at both the individual and team levels.

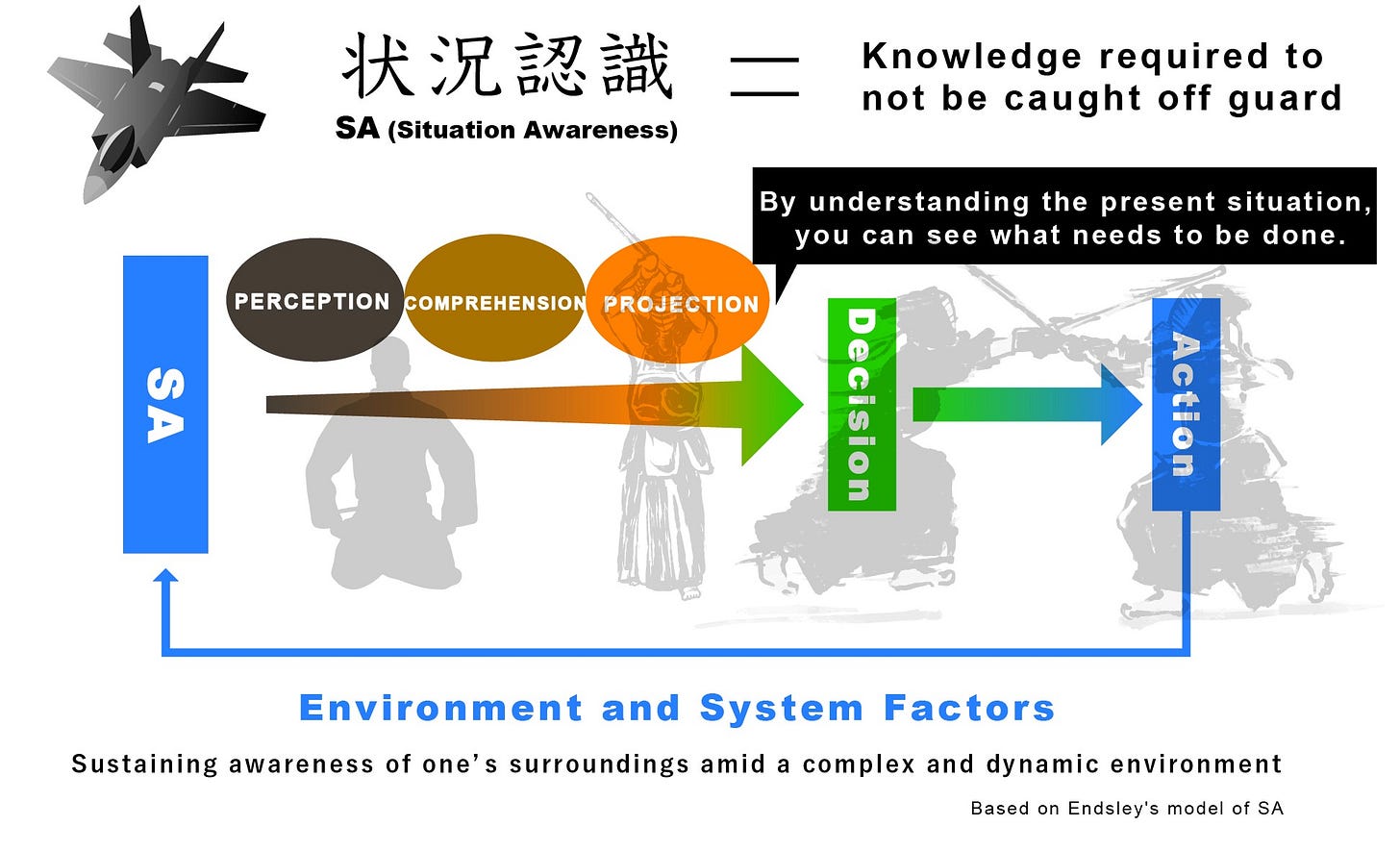

Endsley defined situational awareness as the perception of elements in the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future.[9]

This definition of SA is divided into three levels: (1) Perception, that is, recognising what is happening; (2) Comprehension, understanding why it is happening; and (3) Projection, anticipating what will happen if the situation continues as it is.

Endsley’s research aimed to clarify how pilots can effectively manage complex and dynamic environments while maintaining focus and awareness of critical information. Today, these ideas are applied far beyond aviation. SA is widely used as a means of strengthening decision-making and situational understanding in complex and high-pressure settings, including medicine, law enforcement, cyber security, business, human relationships, education, and even the martial arts.

Summary

In recent years, situational awareness has become a familiar term in Western martial arts discourse and is sometimes presented as a direct equivalent of zanshin. This article has argued that such an equation is ultimately misleading. While SA provides a useful analytical framework for understanding perception, decision-making, and anticipation in high-risk environments, zanshin operates on a different structural level. It does not merely describe a cognitive skill, but compresses posture, awareness, restraint, ethics, and judgement into a single, culturally embedded concept.

For this reason, zanshin resists precise translation. Rendering it simply as “awareness” or “situational awareness” strips away much of what gives the term its distinctive force within Japanese budo. Rather than translating zanshin, it may be more accurate to leave it untranslated, allowing it to function as a technical term that names a particular way of being in combat, one that extends beyond perception into conduct and character.

At the same time, the appeal of zanshin beyond Japan is not difficult to understand. When introduced to practitioners with no prior exposure to budo, the idea resonates strongly, precisely because it articulates something widely felt but rarely named: the demand to remain fully present without excess, to maintain vigilance without aggression, and to act decisively without abandoning ethical restraint. In this sense, zanshin speaks not only to martial practice, but to a broader human concern with how awareness, judgement, and self-control are sustained under pressure.

Just as earlier Japanese terms such as SENSEI, SENPAI, DOJO, and OSS have entered global usage, it is conceivable that ZANSHIN may one day do the same. If so, it will not be because it names something uniquely Japanese in opposition to other traditions, but because it offers a concise and powerful expression for a complex constellation of attitudes that many cultures have recognised, but few have captured in a single word.

[1] Oda Yoshiko hoka, “Nihon kendo KENDO no ‘zanshin’ to Kankoku kendo KUMDO no ‘sonsim’ — kyōgi kisoku no kyōtsū rikai kara —” (2016), Budōgaku Kenkyū, vol. 49, Supplement, p. 84.

[2] Michael Chidester, The Long Sword Gloss of GNM Manuscript 3227a, HEMA Bookshelf, 2021, p. 16

[3] Guy Windsor, The Art of Sword Fighting in Earnest: Philippo Vadi’s De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, (self-published) 2018, p. 123

[4] Gregorio María Dueñas, Ensayo de un Tratado de Esgrima de Florete, Toledo, 1881, p. 133. Available online here. https://bnedigital.bne.es/bd/es/viewer?id=5813efd5-a3da-4c1a-8ae7-7d19fd85d2c8&page=135

[5] Mike Spick, The Ace Factor, 1989, p. 15. I owe a debt of gratitude to Meik Skoss for putting me on to Spick’s book c. 1989.

[6] Ibid., p. 14.

[7] Johannes Werner, Boelcke der Mensch, der Flieger, der Führer der deutschen Jagdfliegerei (1932). Translated as the Knight of Germany: Oswald Boelcke – German Ace, by Claude W. Sykes, Greenhill Books, 1985, p.p. 183-4.

[8] Spick, p. 165

[9] M. Endsley, “Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement”, Proceedings of the Human Factors Society 32nd Annual Meeting, 1988, p. 97.

No comments yet.