Budo Beat 50: Before the Kettle Boils – Budo, Tea, and the Practice of Restraint

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

It is New Year’s Eve as I finish this. Actually, most of what follows was written over the previous days, but I held off posting it until I could take some decent photographs at an annual gathering I try not to miss. Each year, my old friend Randy Channell, a Canadian tea master and fellow long-term Kyoto resident, hosts his Jōyagama.

Jōyagama, meaning “watch night kettle”, is a tea gathering held on New Year’s Eve. Guests are received with soba noodles, warm sweets and usucha (thin tea) as the night is kept in quiet vigil. Traditionally, when the gathering draws to a close, the charcoal fire used to heat the water is not put out, but gently buried beneath ash (uzumibi). The next morning, that same fire is uncovered and used as the first charcoal to prepare hot water for Obukacha, the tea of the New Year. Rather than severing one year from the next, the practice allows them to flow into each other. It is chanoyu expressed as continuity, hospitality, and attentiveness, and in a small but tangible way, a ritual oriented toward peace and goodwill.

As a budoka, I have long felt that budo and tea sit naturally side by side. Well, TBH that’s mainly because Randy insists that’s the case. But he’s right. One deals openly with conflict, the other with calm, but both are disciplines of restraint, presence, and respect. Both budo and tea ask us to meet others without excess, to act decisively without aggression, and to leave the space better than we found it. With that in mind, this felt like the right moment to post a piece about budo and peace. I know! A little bit too serious for the festive season, but here we are.

Admittedly, this is partly inspired by what a bloody shitty, violent year 2025 has been. As one BBC journalist who has spent decades covering wars put it, he has never known a year as worrying as this one, not only because of the number of conflicts, but because of their wider geopolitical consequences.

When people talk about budo and peace there is often an awkward WTF pause. “Good in theory, yeah. But let’s get real here” kind of healthy cynicism. So, let’s take a look at this theory. The key is in the character for the bu (武) in budo itself. Traditionally it is explained as 戈 & 止. The character 戈 refers to a halberd or spear, a weapon designed to kill, and 止 means “stop”. 武, then, is not the celebration of violence, but the act of stopping it. “Stop the weapon”. Read that way, budo is a discipline concerned with how conflict is avoided or thwarted.

Some might object, “No, you romantic dreamer. It means to stop somebody with the weapon”. After all, budo deals in violent acts of striking, cutting, throwing, stabbing, jabbing, choking, and general snotting. It comes wrapped in the vocabulary of combat, victory, defeat, and domination. To suggest that it might contribute to peace can sound naive, or worse, like a marketing slogan dreamed up by someone in the “Cool Japan” office. I know some will roll their eyes at this and dismiss it as a convenient contrivance. And in a sense, it is. But I’m equally convinced that, like the kettle, it holds water.

This pacifistic way of interpreting bu took shape in Japan at a time when people were sick to death of the literal death and sickness that endless conflict produced, and were looking for a way to live peaceably, or at least with violence without being ruled by it. That historical sleight of hand endorsed by scholars in the Edo period does not make the idea worthless. If anything, it makes it more interesting. And, after several decades thrashing it out on dojo floors across multiple continents, I am completely convinced that budo does have something to offer the wider world. Certainly not as a grand solution, or as a substitute for diplomacy or policy, but as a way of training individuals to live with conflict without being consumed by it.

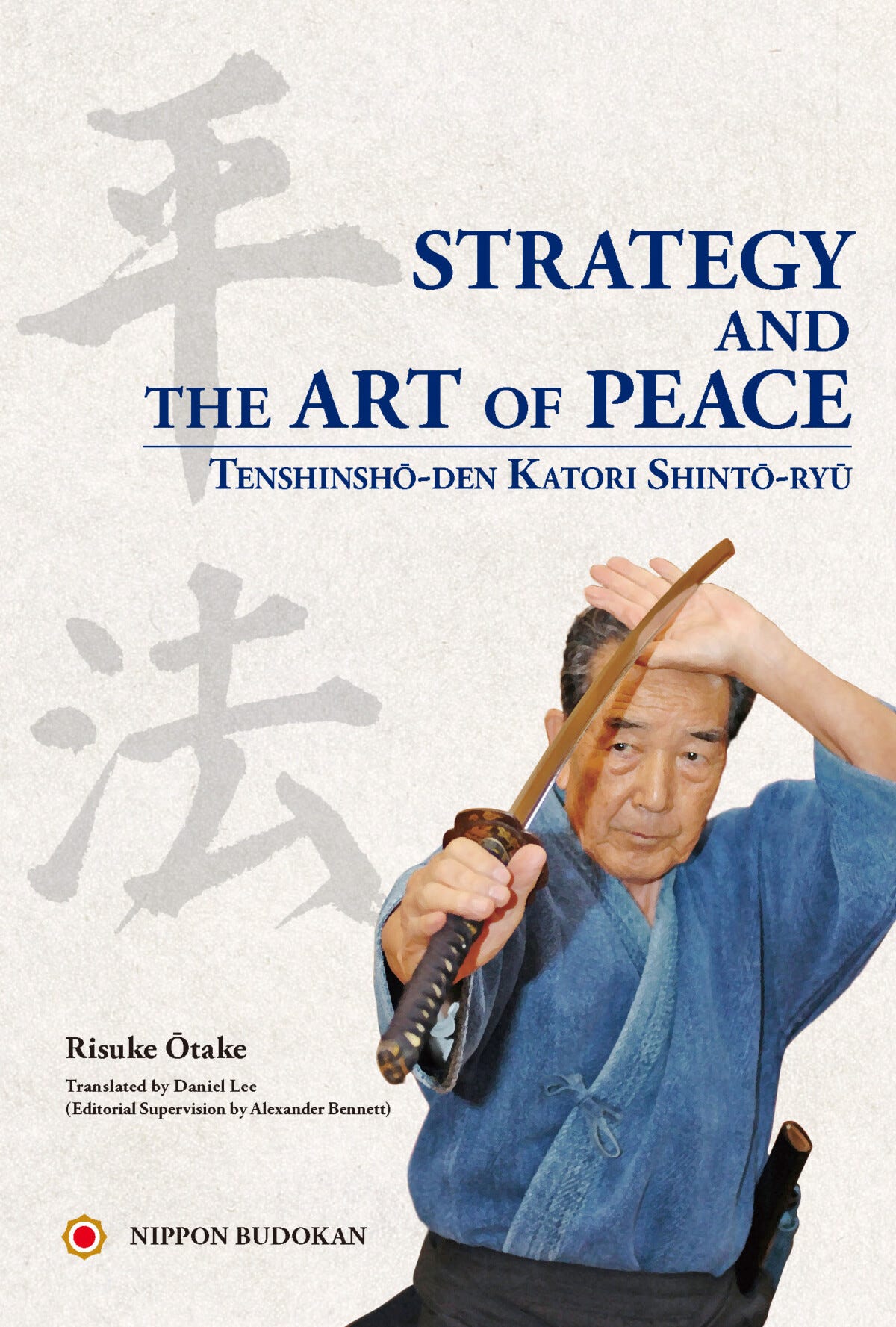

There is a saying often cited in classical martial traditions: Hyōhō wa heihō nari (兵法は平法なり). It continues to circulate not as a historical curiosity, but because it speaks directly to how practitioners are expected to carry the lessons of conflict into everyday conduct. It is usually rendered as something like, “The way of combat is the way of peace”. The phrase is attributed to the brilliant swordsman Iizasa Chōisai Ienao, the founder of Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū.

Hyōhō refers to methods of war or strategy, while heihō, which is pronounced almost the same, shifts the meaning toward balance, order, and restraint. War and peace are not treated as simple opposites, but as points along the same continuum. The issue is not whether violence exists, but how it is held in check.

A well-known anecdote from the same tradition, sometimes called the “teaching of the bear bamboo” (kumazasa no oshie), makes this point in a more oblique way. According to the story, Ienao sat down among thick stands of bamboo grass, allowing the flexible stalks to support his weight. From a distance he appeared to be floating, suspended without effort. Those who came intending to challenge him found the sight somewhat unsettling. Many are said to have abandoned the idea of a contest altogether and gone home. Nothing to see here, thank you very much! Problem solved without the need to draw swords.

I think that peace is often misunderstood as the absence of conflict.

In reality, conflict is unavoidable. Could it be embedded in our DNA? Are we an inherently violent species? I suspect we all know the answer to this. Human beings always disagree, interests tend to collide, and egos get way out of hand. History, culture, and memory do not line up neatly because these things are constantly in flux and being made up to suit some kind of agenda. So, the question is not how to eliminate conflict, but how to engage with it without escalation, dehumanisation, or ultimate collapse into violent resentment and senseless killing. I think this is where budo quietly does its work.

Anyone who has trained seriously knows that the dojo is not a sanctuary from conflict. It is a controlled environment in which conflict is deliberately invited. Two people face each other with incompatible aims. Both intend to impose their will, and accept the risk of failure, embarrassment, and copious amounts of physical discomfort!

What budo teaches, at its best, is not how to avoid this situation, but how to remain functional within it. Breathing calmly when the heart rate spikes. Thinking straight when the body wants to panic, acting decisively without tipping into rage, accepting loss without humiliation, and victory without cruelty. These are not abstract virtues. They are trained responses, hammered out through repetition in keiko.

One of the least discussed aspects of budo is how quickly it strips away fantasy. You may have an ideology, a national identity, a political stance, or a carefully curated online persona, but none of that survives first contact with someone who is genuinely trying to beat the crap put of you. In keiko, the only things that matter are distance, timing, intent, mind-technique-body coalescence, and how you respond under intense pressure in the moment. Everything else becomes noise.

This has a quietly levelling effect. On the dojo floor, all credentials in the mundane world dissolve. Age, gender, job title, and rank really mean bugger all in the fray. What matters is how you conduct yourself, how you treat others, and whether you take responsibility for your own shortcomings. Again, this is not equality in the abstract sense, but equality in exposure. Everyone bleeds metaphorically, and sometimes literally, in the same way and under the same conditions. And it is always red.

International budo events make this especially clear, perhaps more clearly than any intellectual argument ever could. I have stood in numerous gyms and dojos with people from countries that are officially hostile to one another, bowing, training, laughing, and occasionally arguing over matters of technical interpretation. The geopolitical conflicts don’t vanish, but they are temporarily displaced by something more immediate. We are busy trying not to get hit, and busy trying to improve. And, funnily enough, we need each other to do that!

This matters more than it might appear. Peace is not built only through treaties, summits, or private meetings between stakeholders and the powers that be. It grows out of repeated, mundane experiences of cooperation under strain. Learning, often the hard way, that disagreement does not automatically require enmity. And discovering that the person in front of you is not a symbol or a stereotype, but a human being with strengths, weaknesses, and probably sore knees.

Budo also teaches restraint, which is a deeply unfashionable virtue. In a world that often rewards outrage, escalation, and moral certainty, restraint can look like weakness. On the dojo floor, it is anything but. Real restraint requires control, awareness, and confidence. You restrain yourself not because you are unable to act, but because you choose not to act unnecessarily.

This is visible in one of my favourite concepts, zanshin, which is often looked at as some dramatic pose at the end of a technique. In practice, it is closer to responsible awareness. The recognition that action has consequences beyond the moment of impact. The understanding that stopping cleanly is as important as striking cleanly. That finishing well includes not only keeping vigilance for self-protection after the fact, but also not injuring someone unnecessarily when the point has already been made.

These habits bleed into daily life, whether we notice it or not. People who train for years tend to develop a different relationship with anger. Not an absence of it, but an ability to notice it rising, and to decide what to do with it. That alone would be a meaningful contribution to a world that often seems permanently one bad headline away from collective overreaction!

Related to this, I think another quiet contribution of budo is humility. Real training produces confidence, but it also produces a long acquaintance with failure. No matter how senior you become, there is always someone faster, sharper, or simply having a better day. The dojo never lets you forget that improvement is provisional, and that yesterday’s success does not entitle you to a day of comfort. Furthermore, such humility is not self-deprecation. It’s knowing where you stand, what you can do, and what you cannot. As we have seen in 2025, and well, pretty much forever in social and political contexts, a lack of humility often leads to catastrophic overreach. Budo trains the opposite instinct.

It is also worth mentioning that budo creates enduring communities that cross all boundaries. People train together for decades. They see each other age, struggle, recover, succeed, and sometimes disappear. These long arcs of shared effort produce bonds that are not easily replaced. They are treasured and lasting interactions, and in an increasingly fragmented world, that kind of continuity matters.

None of this means that budo practitioners are morally superior, or that the dojo is a utopia. Hell no!! Budo has its share of politics, ego, abuse, and utter hypocrisy. Anyone who claims otherwise is either inexperienced or dishonest. But the tools are there, embedded in the practice, waiting to be used well or badly.

If budo contributes to peace, it does so indirectly. It does not preach harmony. It trains people to face difficulty without flinching, to respect opponents without romanticising them, and to walk away intact after genuine confrontation. Multiply that disposition across enough individuals, and the social atmosphere shifts slightly, but perceptibly.

At the end of the year, that is about as much as I’m willing to claim. Not that budo will save the world, but that it quietly prepares people to live in it more responsibly. At least, it should. One exchange at a time. One bow at a time, and one decision not to escalate when escalation would be oh so easy.

That may not make headlines. But it is real work, done on cold floors, night after night, by people who keep turning up. And as far as I am concerned, that’s a pretty good note to end the year on.

Tonight, there was tea. A single bowl, fired and opened for this moment, passed from hand to hand at Randy’s Jōyagama. No speeches, declarations, or half-hearted resolutions about the coming year. Just attention, warmth, and the shared understanding that more shit is always close at hand, which is precisely why care matters. In that sense, tea and budo close the same circle. Both acknowledge conflict without glorifying it, and point quietly toward peace, not as an ideal, but as a practice. Happy 2026 to one and all!

No comments yet.