Budo Beat 51: The Mysterious Art of the Cat

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

I translated “Neko no Myōjutsu” (猫の妙術 1727) some years ago in 2014 for Kendo World, and then basically forgot about it, until it resurfaced when I was asked to give a session at Graham Sayer’s Kaizen Kendo Workshop last year.

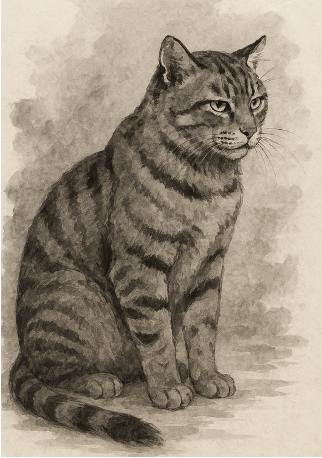

I’m more a dog person than a cat person, but I have long liked this short work for the way it neatly outlines the stages of study in the martial arts. Although it’s framed largely around the sword, what it describes applies far more broadly to training and learning.

The text is traditionally attributed to Issai Chōzan, an Edo-period swordsman/scholar, and takes the form of a light, almost playful dialogue between cats. Beneath this surface, however, it offers a concise and perceptive account of progression in practice, from reliance on technique to a quieter, less deliberate form of mastery. I really love this story, and I figured it’s about time my [slightly simplified] translation saw the light of day. I hope it’s of interest to readers.

“The Mysterious Art of the Cat” (Alex Bennett, 2014)

There was once a swordsman named Shōken. In his house appeared a great rat, bold enough to dash about the room even in broad daylight. Shōken, displeased, shut up the room and loosed his own cat to catch it. Yet the rat, far from fleeing, sprang straight at the cat’s face and bit down fiercely. The poor beast shrieked and fled in terror.

Seeing that his house cat was no match for such a foe, Shōken borrowed a number of cats from the neighbourhood, those felines reputed to be the finest hunters, and set them loose in the room. The rat had taken its stand in a corner of the alcove, and whenever a cat dared approach, it leapt and bit with such ferocity that the cats all shrank back, trembling, unable to advance.

Vexed beyond measure, Shōken took up a wooden sword and pursued the rat himself, meaning to strike it down. But the creature slipped from under his hand and the blows went wide. He swung wildly, smashing doors, shōji screens, and paper walls alike, yet the rat darted through the air with lightning speed, almost as though it might spring upon Shōken’s very face at any moment.

At last he was drenched in sweat. Calling for a servant, he said, “I have heard that half a mile from here dwells a cat of peerless skill. Go at once and fetch it!” The servant ran off and soon returned with the cat in question. To Shōken’s eye it looked dull and sluggish, not the least bit spirited or clever. Still, they thought to try it.

They slid the door open a crack and let the cat into the room. The rat froze where it stood, unable to move. The cat, slow and unhurried, padded over, took the rat lightly in its jaws, and carried it out as though it were the easiest thing in the world.

That night, all the cats gathered at Shōken’s house. They invited the famed old cat, the one said to be without peer, and seated him in the place of honour. Kneeling respectfully before him, the younger cats spoke:

“We are each known as skilful hunters,” they said, “and have long devoted ourselves to the Way of catching rats. Not only rats, but even weasels and otters we have sought to overcome, sharpening our claws and refining our craft. Yet never have we encountered so fierce a rat as the one today. You, however, dispatched it with effortless grace. We beg you, master, reveal to us your secret art, and hold back nothing of your superior method.”

The old cat chuckled softly. “You are all still young”, he said. “Quick of claw, lively of body, but as yet you have not heard the true Way. Thus, when something unforeseen occurs, you are thrown into confusion. But before I speak, tell me first what sort of training you have each undertaken.”

Then one cat, a sleek black tom with keen eyes, stepped forward and said:

I was born into a house that has for generations made its livelihood from hunting rats. From my kittenhood I have trained without cease. I can leap some seven feet clear over a screen, or slip through the smallest of holes. There is no swift or subtle trick I cannot perform. I feign sleep, then spring suddenly to my feet; I can even snatch a rat running along the beam of the ceiling, and I have never once failed in the hunt. Yet today I met a foe of unexpected strength and suffered a defeat most shameful. I confess it has wounded my pride deeply.

The old cat nodded and replied:

All that you have practiced is but movement. You have not yet escaped the bondage of a mind that aims and strives. In olden days, when masters taught movement, it was not the motion itself they valued, but the principle behind it. For that reason, their forms were simple, yet contained within them the utmost truth of the Way. But those who came after devoted themselves solely to motion, saying, if I do this, then that will follow, creating ever more elaborate techniques, competing in displays of skill, and thinking the teachings of the ancients insufficient. They relied on cleverness and invention, until at last their art became no more than a contest of tricks.When cunning reaches its limit, it is of no further use. Those who depend only upon their cleverness fall into this very trap. Wisdom may be the working of the mind, but if it is not grounded in reason, if one gives oneself wholly to skill alone, that becomes the root of falsehood. The clever mind, unanchored in truth, often turns upon its owner and brings harm instead of mastery. Reflect upon this, and continue your study with care.

Then a great tiger-striped cat stepped forward and said,

I hold that in the martial arts, the state of ki, the vital spirit, is of the utmost importance. For many years I have devoted myself to the cultivation of ki. Now my ki is utterly untroubled and exceedingly vigorous, filling heaven and earth, as it were. In spirit I trample my foe beneath me, gaining victory before the contest even begins. I move in accord with the rat’s cry, respond to the sound of its scurrying, and never fail to keep pace with its motion. I no longer think about how to act, for the movements arise naturally of themselves. When a rat runs along the beam, I fix it with my gaze and it falls, and I seize it. Yet that fierce rat came upon me unawares and vanished without trace. What can this mean?

The old cat replied,

What you have cultivated is nothing more than ki acting through force of momentum. You rely upon your own strength, and that is not the proper or rightful working of ki. When you seek to overpower your enemy’s ki, your enemy in turn seeks to overpower yours. What will you do when you meet one whose ki cannot be broken? When you try to cover and crush your enemy’s ki, your enemy will strive likewise to cover yours. What then, when you face one whose ki cannot be covered? Why assume that only you are strong and that all others are weak?What you feel as an untroubled and mighty energy filling all between heaven and earth is but a manifestation of ki. It may resemble the ‘great expansive ki’ spoken of by Mencius, but in truth it is not the same. Mencius’s ki was firm because it rested upon clarity of mind. Yours is strong only because it rides the swell of force. The workings of the two are therefore entirely different, as different as the steady current of the Yellow River and the raging flood of a single night.And what of one who does not yield to the pressure of ki? There is a saying that a ‘cornered rat will bite the cat’. When driven to despair, the rat relies on no one, yet presses forward with desperate resolve. It forgets life, forgets desire, seeks no certain victory, and cares nothing for its own safety. In such a state, its spirit is hard as steel. How could such a creature be subdued by mere force of ki?

Then a grey-furred cat of some years advanced quietly and spoke as follows:

What you have said is indeed true. Though the tiger-striped cat’s ki is vigorous, its presence takes on a visible form, and whatever has form may be perceived, however faintly. I, on the other hand, have long cultivated the training of the heart. I do not force my energy, nor do I contend with others. I maintain harmony and continue in that state. When my opponent’s ki grows strong, I join with it and follow its movement. My art is like a silken curtain that receives a thrown pebble. It absorbs the blow without resistance.[1] Even should a mighty rat appear and seek to oppose me, it finds no footing from which to do so. Yet today’s rat neither yielded to force of ki nor responded to harmony. Its coming and going seemed almost divine. Never have I seen such a creature.

The old cat replied,

What you call harmony is not the natural harmony of things, but an intended harmony born of will. You strive to step aside from the edge of your enemy’s energy, yet even the faintest trace of such intention will be sensed by your foe. If you seek harmony deliberately, your ki becomes clouded and sluggish. Whenever the mind acts with intent, it blocks the workings of the natural sense. And when that natural sense is obstructed, from where can the subtle art arise?When one neither thinks nor acts with intent, but moves in accord with the natural sense of the moment, there is no sign or form that appears before the movement itself. When no form is shown, there is nothing in this world that can truly stand against you.

The old cat continued to speak.

Do not mistake my words. I do not mean to say that all your training has been in vain. Dōri and ki are of one essence.[2] Within movement itself lies the utmost and rightful principle of the Way. Ki serves the body as its instrument. When that ki is open and free, it responds without limit to all things. When it is harmonious, there is no struggle of force, and even should it strike against metal or stone, it will not break.Yet even the faintest trace of calculation or design is already contrivance. Such a state is not the true form in accord with the Way. Therefore, the opponent’s heart will not yield, and instead will harbour enmity toward you. For this reason, I use no art or technique. I simply respond to my opponent in a state of mushin—no-mind—freely and naturally. But even so, the Way has no end. Do not think that what I say is the final truth.Long ago, in the neighbouring village, there lived a certain cat. That cat slept all day, seeming lifeless, almost like one carved from wood. No one had ever seen it catch a single rat. Yet wherever that cat resided, there was not a rat to be found. And when it moved to another place, the result was the same.Curious, I went to visit the cat and asked the reason for this. But it did not answer. I asked four times, and four times it remained silent. No, it was not that it refused to answer. It simply did not know how to put the truth into words. From that, I learned for the first time that those who truly know do not speak, and those who speak do not truly know.That cat had forgotten itself and all things. It held no attachment, no intent, no striving. It had reached the summit of martial virtue, where one no longer kills. I, too, am far from attaining that level.

Shōken listened to the old cat’s words as if in a dream. Then he stepped forward, bowed respectfully, and said,

I have studied the art of the sword for many years, yet I have not reached its ultimate Way. Tonight, in hearing the discourse of each of these cats, I feel that I have grasped the very core of my own path. I humbly ask that you reveal to me something more of its deepest mysteries.

The old cat replied,

No, no. I am but a beast. Rats are my food. How should I know the affairs of men? Yet I have heard something said in passing.The art of swordsmanship is not merely the striving to defeat others. It is the means by which one responds clearly and rightly when confronted with great matters of life and death. A warrior must constantly cultivate this heart and acquire the skill that springs from it, for without such cultivation he has no worth as a man of arms.Therefore, one must come to understand completely the truth of life and death. The heart must not be warped or biased, nor clouded by doubt or confusion. Without relying on cleverness or calculation, one’s mind and ki must be in perfect accord: calm, even, untroubled, serene and deep, the same in every moment. Only then can one respond freely and naturally to any sudden circumstance.If even the faintest attachment or hesitation arises in the heart, it takes on form. When form appears, there is an enemy and there is a self, and thus conflict is born. In such a state, one cannot move freely or act with true mastery. The heart first falls into a place of death, losing its bright and lucid awareness. How then can one stand with clarity and settle a contest with ease? Even if victory is achieved, it is a victory won without understanding. That is not the true purpose of swordsmanship.To be without attachment does not mean to be an empty void. The heart, by nature, has no fixed form, and nothing should be stored within it. If one gathers even a little, ki will cling to that place. When ki clings, one can no longer respond freely to what comes. Where ki leans, it becomes excessive; where it does not reach, it becomes lacking. When excessive, it overflows and cannot be restrained. When lacking, it falls short and is of no use. In either case, one cannot meet change as it arises.When I speak of having no attachment, I mean that the heart stores nothing, ki depends on nothing, there is no foe and no self. When things press upon you, you respond aptly, leaving no trace behind.In the Book of Changes it is written: ‘Without thought, without action; silent and unmoving, yet by sensing, one comes to understand all things under heaven.’He who learns the sword through this path is near to the Way.

Shōken, still filled with wonder, asked, “What does it mean to say that there is neither enemy nor self?”

The old cat replied,

It is because within your heart there exists a self that an enemy also appears. When there is no self, there is no enemy. The very notion of an enemy arises only through opposition, like yin and yang, or water and fire. All things that possess form or image have their counterpart. Yet if within one’s own heart there is no form, then there is nothing to oppose it. Without opposition, there is nothing to compare with. This is what is meant by having neither enemy nor self.When one forgets both oneself and the other, and dwells in a state that is deep, still, and without disturbance, then all becomes harmonious and one. Even if you should break the enemy’s form, you do not perceive it. No, it is not that you fail to perceive it, but rather that you do not dwell upon it. You simply move as you are moved, in accord with what is felt.

The old cat continued.

When the heart abides in that deep, still, and undisturbed state, the entire world becomes the world of one’s own mind. In that state, there is said to be no right or wrong, no love or hate, no attachment or obstruction. The sensations of pleasure and pain, gain and loss, do not intrude. Vast though heaven and earth may be, they are one with the heart, and nothing need be sought beyond it.The ancients said: ‘When there is dust before the eye, the Three Worlds grow narrow; when the heart is without trouble, a lifetime is broad and free.’If a mote of dust or grain of sand enters the eye, you cannot open it. It is because something alien enters what was originally clear and open. This is but an example, showing how the eye’s function mirrors the working of the heart.

The old cat spoke again.

Even if one should be surrounded by ten million enemies, and the body be cut to pieces, the heart remains one’s own. No enemy, however great, can touch it. Confucius said, ‘The general of three armies may be taken, but not the purpose of a single man.’Yet if confusion arises within oneself, that very heart becomes an ally to the enemy. That is as far as I can speak. The rest must come from within you. Reflect deeply, and find your own answer.Teaching means only that the master imparts the art and points out the principle. The true meaning must be realised by the student himself. This is called self-attainment. Some call it mind-to-mind transmission, others the teaching beyond words. It does not mean to turn away from teaching, but rather that there are truths which even the teacher cannot convey. This is not limited to Zen. From the Way of the sages to the innermost workings of martial arts, all genuine realisation is transmitted from heart to heart (ishin denshin), beyond words and letters (kyōge betsuden).Teaching, in truth, already exists within the one who receives it. The teacher merely indicates what the student has not yet seen for himself. It is not something handed down from without. For that reason, it is easy to teach, and easy to hear. Yet it is difficult to see clearly what lies within oneself and make it truly one’s own. That is what is meant by seeing one’s true nature (kenshō). Enlightenment is the awakening from the dream of delusion. Awakening and enlightenment are not two things. They are one and the same.

[1] “Curtain” or ibaku here refers to a hanging or draped screen that, by extension, symbolises a soft yet impenetrable defence. In other words, one that absorbs and nullifies attack without visible strain.

[2] Dōri (道理) refers to the natural and moral principle underlying all true action. It is both rational law and the rhythm of nature itself. When ego or intention interfere, technique loses harmony with dōri. Itis the point where art or skill (gei) transforms into theWay.

What follows is a summary of the story I gave participants in the Kaizen Workshop, and what I based my session on. For those who are interested:

“The Mysterious Art of the Cat” in a Nutshell

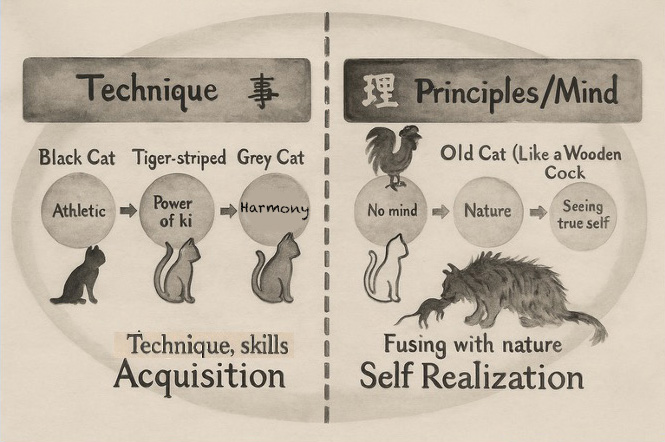

1. The First Cat = Mastery of Technique 技

Story~ The black cat boasts of his agility, his leaps, his speed, and his flawless technique. Yet he fails against the extraordinary rat.

In modern budo~ This is the stage of technical obsession. The long years of polishing strikes, footwork, and timing. The budoka learns every kata and strike precisely, drills endlessly, and can perform beautifully in controlled settings. Yet when facing an opponent of truly high calibre, such a practitioner’s kendo may falter.

Lesson~ Skill alone cannot carry you. Technique divorced from heart and awareness becomes mechanical. The beginner’s ambition to “perfect” form is necessary, but must one day be transcended.

2. The Second Cat = Mastery of Ki 気

Story~ The tiger-striped cat speaks proudly of his overwhelming ki, his spirit that fills heaven and earth. But when he meets an opponent whose will is unyielding, his spirit fails to dominate.

In modern budo~ This is the stage of fighting spirit and presence. The practitioner learns to project energy, to dominate the sen (initiative), to overwhelm through seme and kigurai. Matches become psychological duels. Yet, overreliance on outward intensity becomes counterproductive; such energy can be resisted, neutralised, or turned back.

Lesson~ Spirit is vital, but if it becomes aggression, it hardens into ego. The budo must learn to temper power with sensitivity, to let ki circulate freely without forcing it.

3. The Third Cat = Harmony and Natural Flow 和

Story~ The grey cat speaks of harmony and softness, and of joining with the opponent’s energy and yielding like a curtain to a thrown stone. Yet even his cultivated harmony fails before the divine rat.

In modern budo~ This stage marks the transition to maturity and balance. The budo no longer fights to win, but to connect. There is composure, soft eyes, calm breath, and timing that adapts to the opponent. One can yield without collapsing, attack without tension.

However, harmony that is consciously constructed (“I will be harmonious now”) is still artificial. There is still intention, and thus a trace of ego.

Lesson~ True harmony cannot be planned. It arises spontaneously when one ceases to manipulate or anticipate. The practitioner must learn mushin no kamae (stance of no stance).

4. The Old Cat = Mushin and Naturalness 無心

Story~ The old cat uses no technique, no spirit, no contrivance, only natural response. His ki neither presses nor retreats. He leaves no trace.

In modern budo~ This represents the stage of inner freedom. The practitioner’s movement arises naturally, unforced, unpremeditated. Seme and strike are one and the same. The opponent attacks into one’s ma and is struck without knowing how. The mind is empty, yet fully alive.

Lesson~ This is mushin, or action without obstruction or self-reference. Victory and defeat no longer matter; what remains is clarity of perception and unity with the moment.

5. The Wooden Cock/Cat = Transcendence of Budo 木鶏

Story~ The cat of the neighbouring village does nothing, sleeps all day, and yet no rats exist wherever it stays. Its very being radiates mastery. It has forgotten self and object, life and death.

In modern budo~ This is the final stage of embodiment, where presence itself is enough. The advanced budoka no longer does budo. He is budo. Merely stepping onto the floor changes the atmosphere. Words and form fall away. It is the state sometimes glimpsed in the highest ranks. Those who “win without striking.” Their calm itself resolves conflict.

Lesson~ This is shinbu, the divine virtue of the sword. The practice ceases to be about technique, competition, or even self-improvement. It becomes living harmony with the Way.

6. Shōken’s Realisation = The Human Path 道

Story~ The swordsman Shōken listens to the cats and finally understands that swordsmanship is not about defeating others, but about clarity in life and death, and responding freely to whatever arises.

In modern budo~ Shōken represents the reflective budoka. That is, one who, through decades of training, realises that the ultimate opponent is oneself. He learns that budo is a lifelong path (michi), not a sport. He moves from self-assertion to self-understanding.

Lesson~ To transcend technique, spirit, and intellect, one must return to simplicity. To act without attachment, to live with awareness. Budo becomes not what you do, but how you are.

7. The Underlying Teaching = From Form to Emptiness, from Emptiness to Form 見性

Across all these stages runs a single thread: each level is both necessary and temporary.

- First you train the body (waza)

- Then you train the spirit (ki)

- Then you train the heart (kokoro)

- Finally, you forget training and simply are

This mirrors the natural progression in the lives of serious budoka: youthful intensity, competitive spirit, mature calm, and finally quiet wisdom. The Old Cat’s teaching reminds us that the end of budo is the return to ordinary mind. That is the moment when, without thought or effort, one meets life and death as they come, and leaves no trace behind.

No comments yet.