Budo Beat 55: The Perpetual Observance of Etiquette

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The following is a translation of No. 9 of my 25-article series titled “The Philosophy of Zanshin” (残心の哲学) published in Japanese in the Nippon Budokan’s monthly magazine, Gekkan Budo (“Budo Monthly”, September 2023, pp. 32-38). It’s a rough translation, but I hope it offers some insight. You can read the previous articles in this particular series at the following links:

No 1. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The Essence of Budo”

No 2. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin (Part 1)”

No. 3. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 2)

No. 4. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 3)

No. 5. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 4)

Zanshin and Keiko (Part 1) – The Perpetual Observance of Etiquette

Introduction

In recent years, supporters of the Japanese national football team have created what international media have called a “new tradition”, one that has drawn considerable global attention. After watching their team play, they collect rubbish, sort it carefully, place it into bags, and leave the stadium stands remarkably clean.

This custom has been widely praised around the world as a model of sportsmanship and respect toward the host nation. It not only maintains the cleanliness of the stadium, but also conveys a message of humility and gratitude to local communities and event organisers. Their actions demonstrate deeply rooted cultural values that transcend sport itself: a sense of responsibility and consideration for shared spaces.

In July to August 2023, the FIFA Women’s World Cup was held in my home country of New Zealand and in Australia. As expected, this “new” Japanese tradition continued there as well, and local newspapers were quick to highlight the exemplary manners of Japanese supporters. When asked, “Why do Japanese fans clean up after themselves?” one Japanese replied: “We were taught that it’s only natural to leave a place cleaner than it was before we arrived. And that we should always express our gratitude.” Japanese players, too, have been praised for carefully cleaning their dressing rooms and leaving letters of thanks for local staff.

This scene offers a compelling non-budo illustration of zanshin (continued vigilance) and rei (respect and manners) expressed in everyday life. Even after the match has concluded, whether in victory or defeat, composure is maintained and respect continues to be shown. The attitude does not end with the final whistle; it lingers on regardless of whether the media is watching or not. In an era marked by relentless and rapid change, many inherited values are questioned, and not all deserve preservation simply by virtue of age. Yet what this example suggests is that certain dispositions—gratitude, restraint, consideration for others—remain deeply relevant. Within budo training (keiko), these very qualities are consciously cultivated and transmitted. But they do not float abstractly under the label of “tradition”. They are embedded in the concrete routines of daily practice — in how we enter the dojo, how we face one another, how we begin and end a session. To understand how rei functions in budo, we must therefore look first at the nature of keiko itself, for it is within the structure of training that the spirit of respect takes form.

What is Keiko?

Before examining rei more closely, we must first pause and consider the broader framework within which it operates. In the “Budo Charter”, rei does not appear as an isolated virtue but within the explanation of keiko itself. In other words, etiquette is not an optional accessory to training; it is embedded in the very definition of what training means.

Article 2 of the “Budo Charter” states the following about keiko (training): “When training in budo, practitioners must always act with respect and courtesy, adhere to the prescribed fundamentals of the art, and resist the temptation to pursue mere technical skill rather than strive towards the perfect unity of mind, body and technique.”

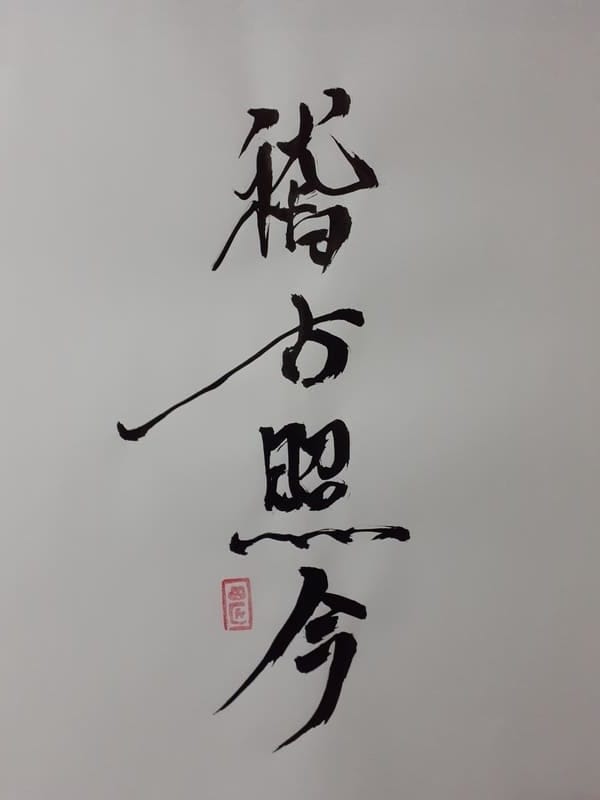

In this formulation, respect and courtesy are presented not as external formalities, but as integral to the process of training itself. Etymology of the word keiko can be found in classical Chinese texts such as the Shàngshū’s Yáodiǎn Shujing (Book of Documents), particularly in the “Canon of Yao”. In Japan, the term first appears in the preface written by Ō-no-Yasumaro to the Kojiki. There we find the phrase: “By examining antiquity,[1] what has fallen into decline in custom and moral example is set right. By illuminating the present (shōkon), nothing is left undone in sustaining the classical teachings when they stand on the brink of extinction.” In other words, it means to reflect upon the past in order to clarify the present. By studying history, we come to understand how the present state of affairs has been reached through the passage of time, and by extension of that, how we can move into the future.

According to the educational philosopher Nishihira Tadashi, “From the medieval period onward, within the thought of the various artistic ‘Ways’, the meaning of ‘polishing oneself through keiko’ became stronger. However, the terminology was not fixed and was used interchangeably with terms such as ‘self-cultivation’ (shūyō), ‘ascetic training’ (shugyō), and ‘discipline’ (shūren)” (Keiko no Shisō, 2019, p. 24).

In twelfth-century France, Bernard of Chartres, a leading figure of the School of Chartres who further developed Platonic thought, famously remarked that “We are like dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants, so that we can see more than they, and things at a greater distance—not by virtue of any sharpness of sight on our part, or any physical height, but because we are carried high and raised up by their giant stature.” It is a sentiment that closely parallels the philosophy of keiko in budo. The budoka inherits techniques, principles, and wisdom accumulated over centuries. To be involved in budo is to be entrusted with the legacy of a Way. One is obliged to question, adapt, and utilise that accumulated wisdom and to serve as a bridge between predecessors and future generations. This is the oft-stated ideal of budo.

Although both the words renshū and keiko are often translated as “practice”, they differ in nuance and scope. Renshū usually refers to focused repetition aimed at mastering a particular technique or physical skill. Keiko, by contrast, carries a meaning that extends beyond technical training. It carries connotations of spiritual growth and self-cultivation. In other words, keiko is not merely about conditioning the body; it is about cultivating one’s character. That is the deeper significance of the “Way” (michi or dō), the broader philosophical tradition in which budo is understood not merely as technique, but as a lifelong path of self-cultivation.

And so, within the worlds of budo and the traditional performing arts, the word keiko is regarded as almost sacred. If only I had a hundred-yen for each time I was told “Keiko is NOT the same as training or practice in the sense of sports.” Outside Japan, it is often translated simply as “training” or “practice”, yet the word keiko itself is gradually becoming an international term, now commonly used within the global budo community.

The Changing Manner of Manners in Budo

Let me now turn to the question and place of “rei” in budo. Watching a modern budo competition or keiko session carefully, the historical layering of etiquette formalities becomes visible in lived practice. In kendo, for example, the competitors step forward, bow to the shōmen, turn to face one another and then perform a mutual bow, advance three steps and go into sonkyo, lowering themselves in controlled symmetry before rising into kamae. After the bout, regardless of the result, they return to sonkyo, stand, bow once more, and withdraw without display. But, what appears seamless and ancient is, in fact, the product of careful standardisation shaped over time.

The meaning and practice of “forms of etiquette” (reigi sahō) in budo did not emerge fully formed from some timeless past. It evolved in response to shifting cultural, social, and political conditions, particularly from the late Edo period (1603-1868) into the modern era. To be sure, the samurai class for much of its existence was famously attentive to matters of protocol. Schools such as Ogasawara-ryū specialised in courtly etiquette, ceremonial procedure, and ritual propriety, codifying everything from modes of bowing to the correct handling of weapons in formal settings. Yet this does not mean that what we now recognise as “budo etiquette” existed in a fixed, unified form.

In earlier times, rituals of etiquette in martial training was often local, domain-specific, and shaped by the customs of particular ryūha rather than nationally consistent. It commonly involved forms such as sonkyo, a crouching bow with one knee and hand touching the ground. This gesture reflected established Japanese customs and embodied the hierarchical and ritual sensibilities of the period. Only in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as budo was reorganised within modern educational and institutional frameworks, did etiquette become increasingly systematised. As Japan entered the Meiji era (1868-1912) and engaged more directly with the West, ideas about posture, discipline, and public comportment began to change.

More upright modes of standing and bowing gradually entered martial practice, influenced in part by modern (=Western) military and police training systems that emphasised straight posture, uniformity, and disciplined bearing. The surge of nationalism following the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) further accelerated this process. The government sought to cultivate discipline, loyalty, and moral rectitude through education and physical training. Debates over seemingly minor matters, such as whether female students should point their toes inward in the traditional manner or outward in accordance with Western physical training, reveal how deeply questions of identity and modernity were embedded in discussions of etiquette. Reihō (formalised codes of etiquette) became a site where tradition and modernisation were negotiated rather than simply preserved.

The transformation of etiquette was not random but increasingly systematised, especially as budo was incorporated into school education. In 1911, the Ministry of Education published the “Sahō Kyōju Yōkō” (Guidelines for Teaching Etiquette), which standardised sitting and standing methods, including the prescribed sequence of lowering oneself from the left side and rising from the right in seated bowing (saza-uki) — a procedure still observed in kendo and other budo today. These reforms shaped how generations of students learned to move, sit, stand, and bow in daily life, and they left a lasting imprint on budo etiquette as well.

By the 1930s, these developments were reinforced by state efforts to unify and standardise martial practice. This fascinating video produced by the Japanese Ministry of Education in 1930 is well worth a watch as it shows the fastidious detail attached to protocols of etiquette in all walks of life. Although there are no budo scenes in the film, any modern budo practitioner will be able to see the overlap.

Organisations such as the Dai-Nippon Butoku Kai were also commandeered by the government, and promoted nationally framed forms of etiquette, including structured bowing procedures in kendo and the mandatory installation of kamidana (Shinto style altar) in dojo from 1936, thereby sacralising the training space and reinforcing a shared sense of moral, spiritual, and national orientation. What appears today as ancient, unbroken tradition is in fact the result of layered historical adaptation. Modern budo etiquette is best understood not as a relic of the distant past, but as a carefully shaped synthesis of inherited custom, educational reform, Western influence, and national ideology.

What is the Rei Spirit?

If modern forms of budo etiquette are the product of layered historical development, educational reform, and cultural negotiation, the question that follows is what animates it? What gives life to these repeated gestures of bowing, standing, sitting, and facing one another? To answer that, we must turn from form to inner meaning.

The “Budo Charter” (Article 2) instructs practitioners to observe proper decorum from beginning to end. This does not refer merely to outward movements of etiquette, but to the inner attitude that supports them. There is a maxim often repeated in budo that “begins with rei and ends with rei” (rei ni hajimari, rei ni owaru). In a single session of keiko, how many times do we bow? It depends on the budo, but generally speaking, entering and leaving the dojo, bowing to the shōmen, to one’s teacher, to one’s training partners, before and after each exchange. It may well exceed a hundred times in a single session. Yet, we are sometimes warned in the dojo, unless each gesture is carried out with conscious intent, it risks becoming mere formality, an empty “hollow courtesy” (kyorei), which can in fact verge on discourtesy.

The emphasis on this all-important “spirit” of rei has long been deeply rooted in budo. In Yagyū Sekishūsai’s (1527-1606) Heihō Hyakushū (One Hundred Verses on Strategy), we find the line: “Hold the principles of strategy inwardly in reverence; let not your heart be disturbed in the two virtues of rei and gi.” As Yagyū Toshinaga explains in Shōden Shinkage-ryū (1957), this means that the practical application of strategy rests fundamentally upon rei and gi (rectitude).

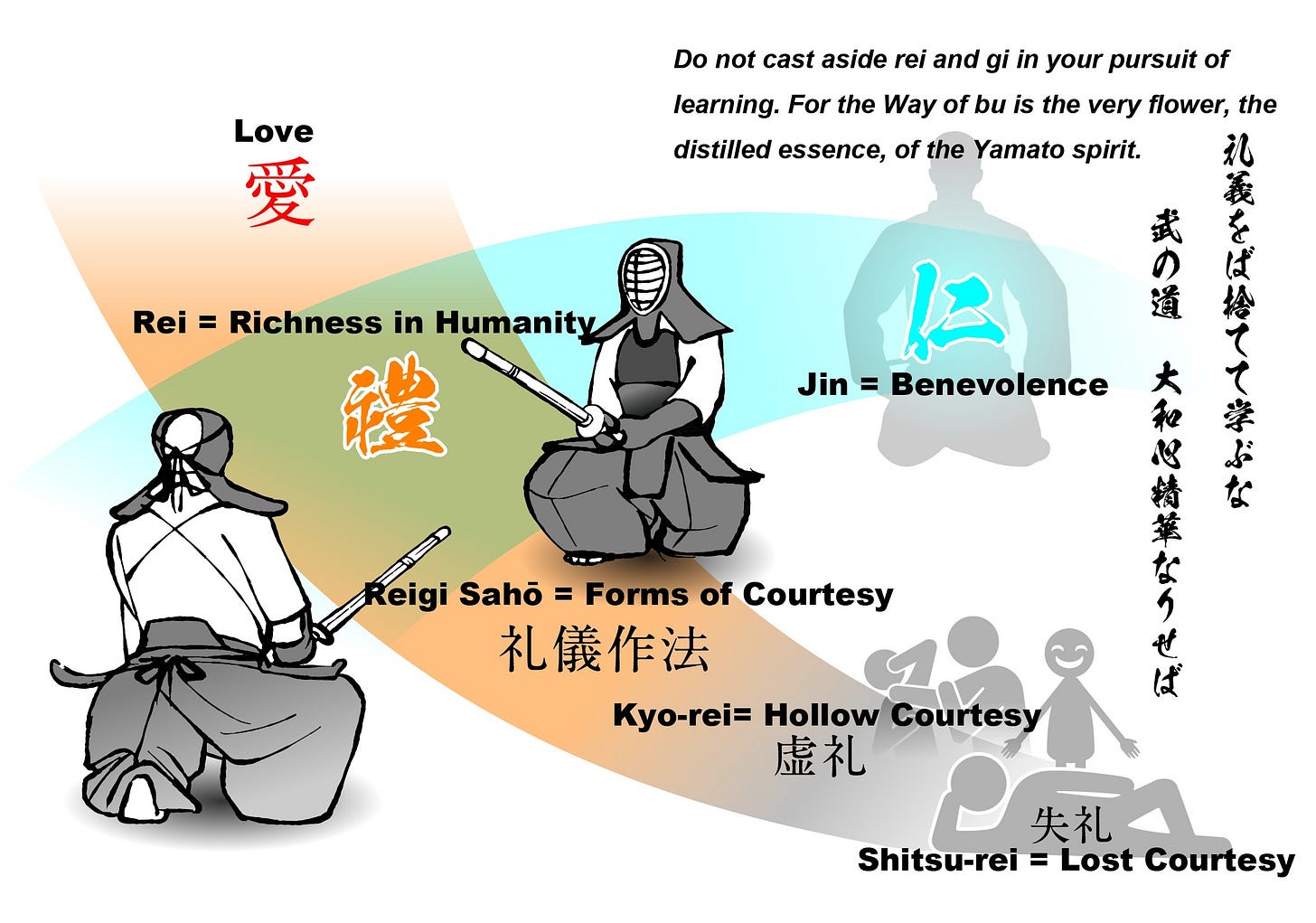

Rei (礼) is usually translated as “courtesy”, “manners”, “politeness” or “ritual decorum”. It also refers to the act of prostration, and in the dojo “Rei!” is called out as a command to bow. In budo terms, however, it is not merely bowing. It encompasses knowing one’s place, showing respect, observing proper conduct, and maintaining outward composure. In short, it regulates behaviour. Gi (義) is usually translated as “righteousness”, “justice”, or “moral rectitude”. It refers to doing what is right because it is right. In the samurai context, it signified integrity, moral backbone, and acting according to principle rather than convenience. Together, reigi denotes proper conduct grounded in moral awareness. In modern Japanese it is often rendered simply as manners or courtesy, but within budo these intertwined virtues form one of the central foundations of its ethical thought.

The character for rei (礼), written in its older form as 禮, consists of the 示 radical (associated with ritual or divine manifestation) and 豊 (abundance). Etymologically, it conveys the sense of “manifesting abundance.” This abundance does not signify material wealth, but rather a richness of humanity, an inner fullness expressed outwardly through refined conduct. It suggests depth of heart and cultivated sensibility made visible in action. In Confucian thought, rei is one of the so‑called “Five Constant Virtues” — benevolence (jin), righteousness (gi), propriety (rei), wisdom (chi), and trustworthiness (shin). Within this framework, rei denotes the proper ordering of human relationships grounded in a heart that respects others. It is therefore not merely a system of manners or behavioural rules, but the sincere embodiment of moral awareness in everyday interaction.

The ancient Chinese text Liji (Book of Rites), which articulates both the regulations and inner spirit of ritual propriety, states: “The beginning of propriety (rei) and righteousness (gi) lies in rectifying one’s appearance, composing one’s countenance, and ordering one’s speech.” In other words, rei begins not with grand gestures, but with self-regulation. Its spirit lies in consideration for others. That is, in avoiding the creation of discomfort or unease. It starts with attention to one’s own attire and demeanour. One is expected to maintain a composed and pleasant expression, to exercise care in speech and conduct, and to ensure that one’s presence brings clarity rather than confusion to those around them.

Nitobe Inazō devoted an entire chapter to rei (politeness) in his classic book Bushido: The Soul of Japan (1900). Writing through the lens of his Christian humanism, he argued that the highest form of Japanese politeness, as exemplified by the samurai ideal, approaches love itself. Courtesy, he suggested, is long‑suffering and kind; it is not envious, boastful, arrogant, rude, self‑seeking, or easily angered, and it harbours no ill will. For Nitobe, such politeness was not superficial refinement but an indispensable moral virtue in Japanese society. At the same time, he lamented that many merely perform the outer gestures of etiquette without embodying its spirit. True politeness, he maintained, must arise from compassion (jin) and genuine concern for another’s feelings. When behaviour is motivated solely by fear of giving offence, it cannot properly be called virtue. At its highest expression, rei approximates love; below that lies a gradual decline: proper form → hollow courtesy → lost courtesy.

Rei as Communication

In kendo matches, if a competitor strikes a decisive point and then celebrates with a fist pump, the point may well be nullified. Such a gesture is interpreted as overt triumphalism, a sign of arrogance, a lapse in zanshin, and a breach of courtesy toward the opponent. At the very moment of victory, what is required is not self-congratulation but composure: a quiet acknowledgement of the exchange that has just taken place. The winner is expected to remain mindful of the other’s disappointment, to recognise that the roles could easily have been reversed. This disciplined empathy, the capacity to hold one’s own success while remaining aware of the other’s position, lies at the heart of rei in budo.

When we bow to our sensei or to the shōmen of the dojo, the gesture expresses gratitude toward those from whom we have received instruction. Bowing upon entering and leaving the dojo is not a quaint custom but an acknowledgement of the training space itself. The dojo is more than a wooden floor; it is a place where ego is meant to be tempered and character forged. To bow before stepping onto the floor, and again when departing, is to mark a threshold — leaving ordinary distractions behind and entering focused discipline. After keiko, bowing once more to the shōmen signifies thanks for having trained safely and sincerely.

Similar gestures appear across Japanese sport. Baseball players bow toward the field before practice or a game. Volleyball teams bow to the court and to one another before the first serve. These understated acts acknowledge that the arena itself deserves respect. Yet budo introduces an added intensity. In keiko and competition we are about to unleash upon one another barrages of techniques that were originally devised to maim or kill. To a casual observer it can look like unrestrained aggression, even violence without regard for the opponent’s well-being. The bow, and the spirit that gives it meaning, therefore carries a heightened ethical weight. It frames what follows as disciplined exchange rather than hostility. In this sense, budo is not isolated from wider sporting culture in Japan, but represents a more philosophically articulated and ethically heightened expression of a shared ethic of gratitude toward place and opponent alike.

![高校野球でおなじみの「整列して、一礼」 ルーツは仙台にあり - 高校野球 [宮城県]:朝日新聞 高校野球でおなじみの「整列して、一礼」 ルーツは仙台にあり - 高校野球 [宮城県]:朝日新聞](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!y_j9!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8adca23e-39fe-4ae1-8864-30949cf1b3d2_640x427.jpeg)

Yet toward the person standing opposite us in keiko or competition, what is required is not hierarchical deference, but empathy grounded in equality. We face one another as peers. The bow becomes a mutual pledge: I will give my utmost; I will harbour no ill will; I trust that you will do the same. “Harmony”, as the old Japanese saying goes, “is realised through propriety”. In the heightened atmosphere of combat, rei is what prevents intensity from collapsing into hostility. Without it, training degenerates into little more than managed violence.

The idea that keiko begins with rei and ends with rei signifies more than the ritualised exchange of “Onegai shimasu” and “Arigatō gozaimashita” before and after practice. It embodies humility, empathy and trust. Metaphorically speaking, we step forward as though into a life-and-death struggle. We intend to overcome the opponent; yet we may just as easily be struck down ourselves. The position is equal. From that equality arises an understanding of the other’s feelings. Minds connect. This is a face-to-face mode of communication grounded in placing oneself in the other’s position. Through empathy — what I believe to be at the very core of budo etiquette — a deeper and uniquely charged form of communication becomes possible.

Rei and the Eyes

If rei is a form of communication enacted through the body, then nowhere is its subtlety more visible than in the eyes.

Making eye contact when bowing to one’s opponent is an extremely important aspect of etiquette in budo. From a typical Japanese social perspective, however, looking directly into someone’s eyes while greeting them may feel unnatural. In some contexts, especially toward a superior, sustained eye contact can even be considered disrespectful. Yet in budo, when one bows to an opponent, one meets their gaze.

I’m committed to keeping my work freely accessible to all budo enthusiasts, wherever they are. If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve found here and would like to support my ongoing efforts and projects, “buying me a coffee” (beer actually), or my books, would make a world of difference. Cheers!

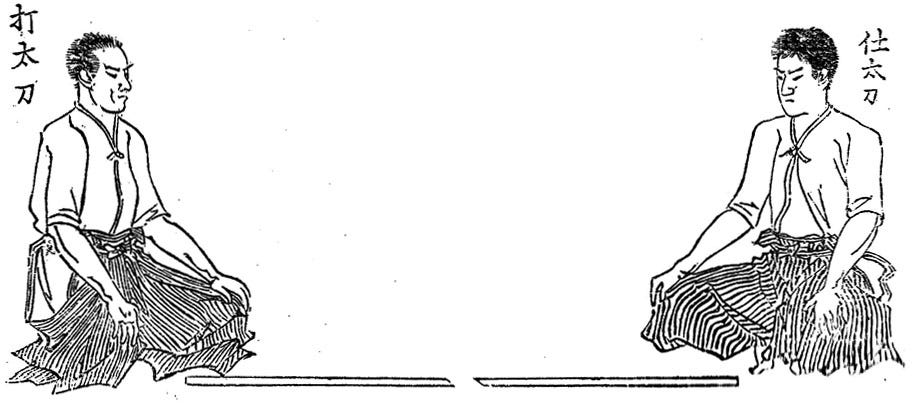

When bowing to the kamidana (altar) or to the shōmen (front) of the dojo, traditional Japanese etiquette dictates that one lowers the eyes and avoids looking directly at the object of reverence. In contrast, in budo, whether performing a standing bow (ritsurei) or a seated bow (zarei) to an opponent, one lowers the upper body while maintaining eye contact. This has a very practical rationale. In an actual combat situation, the moment one averts one’s gaze, it becomes impossible to predict what the opponent might do. At no time is it permissible to relax one’s guard or expose an opening. This is a fundamental principle of zanshin.

The mindset of the old samurai adage “jōzai senjō” (“always as if on the battlefield”) is reflected even in the mechanics of bowing. In seated bowing, the left hand touches the floor first, followed by the right. When rising, the right hand returns first, then the left. This sequence is not arbitrary. By alternating the hands in this manner, one preserves the ability to draw the short sword at the waist at any moment.

At another level, making eye contact during a bow communicates seriousness. To avert one’s gaze is, in effect, to refuse engagement with the other person. Meeting the eyes conveys sincerity and openness; it underscores one’s authenticity and fosters trust. Sustained eye contact also expresses respect for the other’s thoughts and emotions. It has a profound impact on the depth and quality of human relationships, nurturing an atmosphere of mutual respect and understanding.

To observe proper decorum while at the same time looking directly into the opponent’s eyes may appear to contain contradictory elements, humility and vigilance, deference and readiness. Yet precisely in that tension, the spirit of budo reveals itself.

Rei Toward Budo Equipment

We often see professional athletes on television, crushed by failure or frustration, venting their emotions by smashing their own equipment. At times, that passion is even applauded as evidence of intensity. A tennis player destroys a racket. A baseball player snaps a bat. A golfer bends a club. It may provide a momentary release, but from the standpoint of a budoka, such behaviour signals an embarrassing lapse in composure. To treat one’s equipment roughly reflects a serious lack of respect, not only for the implements that make practice possible, but for oneself as an athlete and for the discipline one represents. It also sets a poor example for younger practitioners, implying that defeat or disappointment justifies the uncontrolled discharge of anger. In such acts, the continuity of awareness that characterises zanshin is conspicuously absent.

For that very reason, respect toward one’s training implements occupies an important place within budo culture. Equipment is not disposable gear but an extension of one’s practice. Without it, keiko cannot take place. Keeping armour and weapons clean, handling them carefully, and using them properly expresses gratitude for the traditions of budo and responsibility toward those who trained before us. It also reflects consideration for one’s training partners. Damaged or neglected equipment can lead to serious injury. By caring for one’s tools, one helps sustain an environment in which keiko can be conducted safely, sincerely, and with mutual trust.

Let me take iaido as an example. Practitioners always inspect the mekugi (the peg securing the blade to the hilt) and perform tōrei, a bow to the sword. After practice, the blade is cleaned, lightly oiled, and carefully returned to its scabbard. Treating one’s equipment almost as if it were alive is characteristic of budo. One never steps over weapons. I was once taught by a kendo teacher that when removing my men, I should raise it in front of the face so as not to expose my flushed, breathless expression to others. The inside of the men is wiped first with a tenugui. This is done to express gratitude to the armour that protected me during practice. Only after that should I wipe my own face and set the men down. It is difficult to think of many other sports in which such gratitude is shown toward equipment to this extent.

Regrettably, in recent years I have begun to sense that equipment is not always treated with the care and reverence it once commanded. Armour is left uncleaned, shinai are not maintained carefully, and tools that should embody the dignity of the art are reduced to mere training gear rolled up and stuffed unceremoniously into a gym bag. Rather than repairing worn items, tightening fittings, or learning how to care for them properly, it has become all too easy to go online and order inexpensive replacements with a few clicks. Convenience has quietly replaced commitment. Such shifts may seem minor, yet they reflect broader changes in attitude toward practice itself. The increasingly difficult circumstances faced by budo equipment artisans, whose livelihoods depend upon the preservation of traditional craftsmanship, deserve careful attention. I will return to that issue in greater detail in a separate article.

Some thoughts on Rei Outside Japan

In general, rei is interpreted as “respect”. Many also equate it with “sportsmanship”. Sportsmanship typically refers to virtues such as fairness, self-control, courage, perseverance, and consideration for one’s opponent. It encompasses treating others equitably and respecting both authority figures, such as referees, and one’s competitors.

At its core, sportsmanship involves what might be called the “mutual pursuit of excellence”. The ideal of competition lies in challenging the opponent’s excellence within the framework of agreed rules. From this perspective, sportsmanship means revering the fundamental principles that define the value of the contest itself. It is not merely about obeying rules and playing fairly; it entails actively upholding and elevating the traditions and values of the sport.

Yet when political, cultural, or moral tensions intrude upon the arena, the boundaries of sportsmanship can become far less clear. A recent incident in international fencing illustrates how fragile the balance between form and spirit can be.

In late July 2023, at the Fencing World Championships, Ukrainian fencer Olga Kharlan defeated her Russian opponent, Anna Smirnova, 15–7. After the bout, Smirnova extended her hand for the customary handshake. Kharlan declined and instead raised her sabre, offering a blade tap. She later explained that the gesture was meant to show sporting respect while acknowledging the reality of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine. The International Fencing Federation (FIE), however, initially disqualified Kharlan for failing to carry out the post-match handshake required under the rules. The decision was justified by FIE officials on the grounds that refusing the handshake contravened fencing tradition and the spirit of sportsmanship.

Returning to budo, in Japan people grow up bowing almost unconsciously in daily life. Bowing is certainly not limited to martial arts; it is a traditional practice expressing greeting, respect, humility, and apology. Yet in today’s multicultural societies, to what extent should such forms be strictly observed? Some instructors believe that all practitioners should conform fully to the [Japanese] cultural customs of the art. Others argue that greater flexibility is required when teaching students from diverse backgrounds.

Outside Japan, bowing continues to spark some debate due to cultural, religious, and personal beliefs. Some interpret bowing not as a sign of respect but as an act of submission or subordination. Among foreign practitioners of budo, there are those who refuse to bow for religious reasons. For example, certain Christian denominations regard bowing as a form of worship reserved for God alone. Likewise, some interpretations within Islam discourage prostration or seated bowing to anyone other than Allah.

In some dojos, practitioners bow toward the national flag, toward photos of the founder of the art or past masters. For individuals whose personal or religious convictions make them uncomfortable showing such gestures toward symbols, this can present a genuine dilemma. In my experience with international students and overseas seminars, I have encountered all these situations.

At the same time, it would be a mistake to assume that rei is meaningful only for Japanese practitioners. The ethical substance underlying the gesture—respect, restraint, gratitude, and recognition of the other’s dignity—is not culturally exclusive. What differs is the outward form through which those values are expressed. For someone who did not grow up within Japanese customs, bowing may not carry the same intuitive resonance. Yet the question is not whether one is Japanese, but whether one understands and embraces the relational ethic that the form is meant to convey. If that spirit can be grasped, then rei remains relevant regardless of nationality.

What complicates matters further is that the word rei refers both to the physical act of bowing and to the spirit of respect that underlies it. I explain to students that while form has meaning, what truly matters is the intention and feeling behind the gesture. If one adheres, in an appropriate way, to the cultural expression through which respect is shown, then the spirit of rei can be preserved without reducing it to mere outward motion.

For many non-Japanese practitioners of budo, bowing alone does not always feel sufficient to express respect or gratitude. Thus, at international judo tournaments, one often sees competitors bow to one another and then follow with a hug or handshake. From a Japanese perspective, this may appear curious or even unnecessary. Yet similar scenes can now be observed in Japan as well. In naginata, for example, after finishing practice with a partner, practitioners return to naore (natural posture) and then perform a formal bow. That bow is carried out with proper solemnity, as etiquette demands. And yet, immediately afterward, most step back smiling and say, “Thank you very much” as they bow again. I sometimes find myself wondering what, precisely, the purpose of the first bow was meant to convey!

In recent years, the “fist bump” has also become popular. It is a common sight in various university kendo clubs in Japan: a light bow during practice, followed by the touching of fists. This gesture, I assume, sends a message of respect and encouragement. Traditionalists may well balk at the idea, but look closely and one sees that it functions both as recognition of the other’s presence and as a gesture of solidarity. It raises morale and fuels competitive spirit. What may seem trivial, or even lacking in decorum, can carry deep meaning for younger generations students irrespective of cultural background. That is why I am hesitant to criticise the action.

Besides, as I mentioned above, each classical martial tradition developed its own distinctive forms of etiquette. The etiquette of modern budo was shaped and standardised largely from the late nineteenth through the twentieth century. Yet what has taken shape in one historical moment need not be mistaken for something immutable. Forms evolve. What must endure is the spirit that animates them. Ultimately, rei is not secured by posture or action alone, but by sincerity. And in the end, its true measure lies in how we face the person before us.

[1] Inishie [古] wo kangaeru [稽] = keiko [稽古]. To reflect on the ancient ways and wisdom.

No comments yet.