Budo Beat 23: Kiai to Kanpai in the Dai-ni Dojo

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

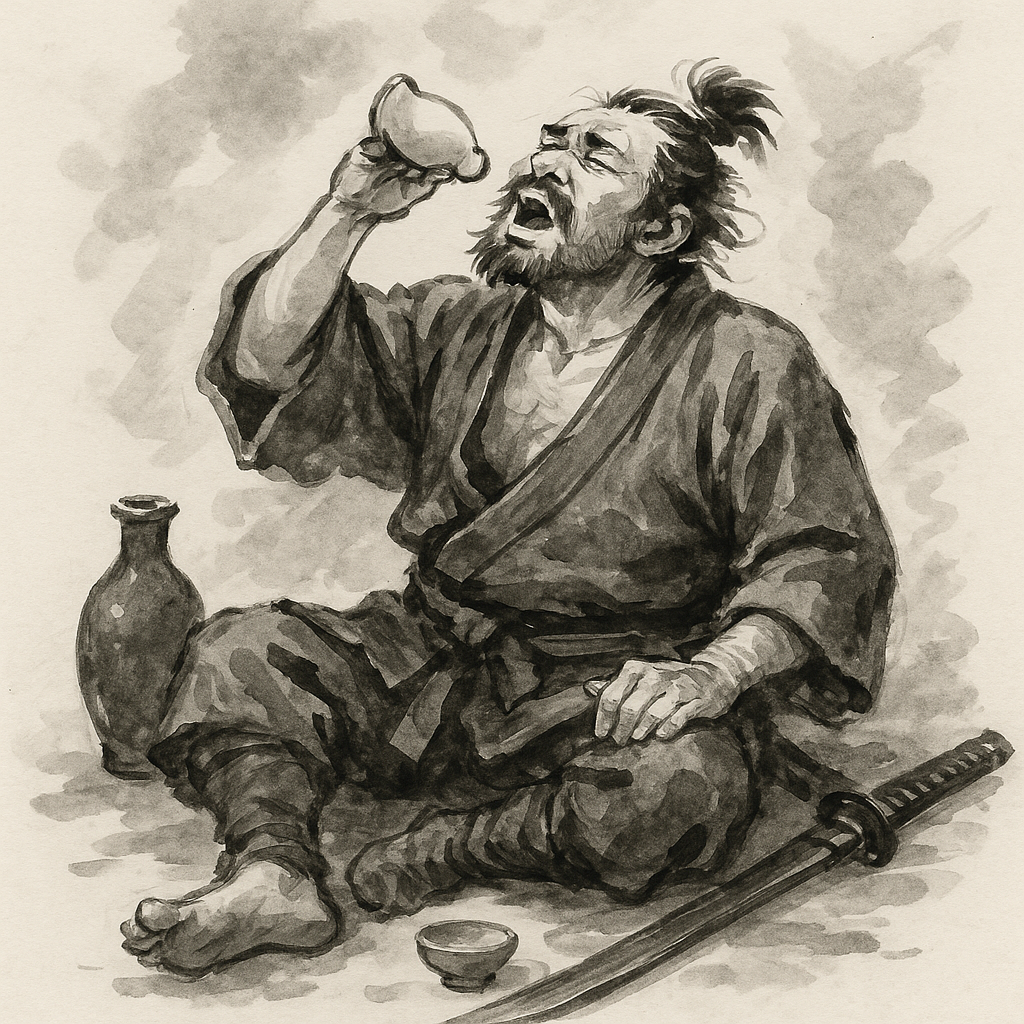

There are certain aspects of budo which are just, well, not good for you or others. In Japan, there’s a distinct culture of drinking in budo—celebrated, expected, and sometimes regretted. It is one of those curious paradoxes, especially in ages gone by, that despite the intense discipline and precise rituals of training in the dojo, the practitioners themselves were often anything but restrained outside. As a fresh-faced student stumbling into Japan back in the days when my knees still bent without protest, I quickly discovered a curious unofficial maxim among kendoka: “If you can’t hold your drink, you’re not much of a swordsman.” There is an even more well-known ‘truism’ gleefully bandied about to justify budo benders: “Budo IS beer…”

It seemed counterintuitive even then, yet irresistibly attractive (especially in the stinking hot summer)—an intoxicating blend of discipline on the floor and indulgence off it. In those days, the post-training festivities, still known affectionately as the Dai-ni Dojo—literally, the “second dojo”—were/are often considered by many as the genuine highlight of practice!

Looking back, it’s easy to romanticise those late-night gatherings. The formalities of bowing, shouting, and striking would give way to raucous camaraderie, earnest philosophising on budo, and an endless torrent of beer and sake that ran like the Kamogawa River in flood season. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that some of my most valuable insights into martial arts philosophy came not during training but amidst the cheerful chaos of these informal ‘debriefing’ sessions. It was here, after all, that one let down one’s guard (and often one’s dignity), sharing candidly the experiences, triumphs, and humiliations of the martial journey.

But this loose approach to self-care was historically ingrained in budo culture. The old-school swordsmen weren’t exactly poster boys for moderation. Tales abound of legendary warriors who trained relentlessly by day and drank prodigiously by night. Yamaoka Tesshū, for example, was known to drink even tables under the table.

Indeed, there is a certain poetic charm in the haiku-like wisdom encapsulated by the phrase, “For a warrior, losing control of oneself through drink is shameful; yet abstaining altogether is equally foolish.”[1] Balance, in other words, was key—but historical balance seemed to swing quite dramatically towards excess.

This is evident in many old Edo period treatises on bushido which encouraged samurai to “live correctly”. If they already were paragons of healthy living, then they wouldn’t need to be told. But what does this “live correctly” thing mean? Daidōji Yūzan, a bushidō thinker of the late Edo period, provides an answer in his classic work Budō Shoshinshū (“Primer for the Martial Beginner”), intended as a guide for young samurai:

“For a samurai, from the moment he picks up his chopsticks on New Year’s morning to celebrate the mochi in his soup, until the evening of New Year’s Eve at the year’s end, the most essential principle is to keep death constantly in mind, day and night.”

At first glance, this passage appears to advocate an intense, passionate lifestyle reminiscent of the warriors of the Sengoku period. However, Yūzan’s idea of “constantly bearing death in mind” actually serves the pragmatic purpose of guiding samurai in their daily conduct as loyal retainers:

“By adhering to the dual path of loyalty and filial piety, one avoids wrongdoing and calamity, keeps the body healthy, lives a long life, and develops a virtuous character.”

Thus, when samurai speak to others, they must recognize that even a single ill-chosen word can have serious consequences, and therefore they must avoid needless arguments. Moreover, regardless of their social status, people often become careless of mortality, succumbing to unhealthy habits such as overeating, heavy drinking, or lustful indulgences. This negligence can lead to untimely death or chronic illness that renders one unable to perform one’s duties. Keeping death constantly in mind, therefore, compels one to practice moderation in eating and drinking, and to exercise strict restraint in matters of sexual desire.[2]

The ideal and reality have, thus, long been at odds. For a martial artist, the typical mantra was “train hard, play harder…” This penchant for brief detours into hedonism led to some unfortunate stereotypes. Martial artists could occasionally be found staggering in streets or picking fights in dim-lit taverns—behaviours that did little for their public image. Indeed, in my own student days of exuberance, there were certainly nights I danced perilously close to shame, though mercifully such occasions were rarely documented for posterity. We didn’t have smartphones back then!

Fast forward three of decades, and things have changed noticeably in Japan. Today’s young budoka are a markedly different breed. They are as likely to sip cola-floats as beer. Some are even attentive to nutritional balance and adequate rest as they are to their footwork and technique. The change isn’t merely generational—it’s seismic. While my own youth was defined by a cheerful disregard for my body’s well-being, the current generation seems admirably intent on preservation. Many now view excessive drinking (and smoking) as something their quaint, antiquated elders once did—about as relatable as cassette tapes and rotary phones.

As I enter what might be called the autumn of my life, I find myself increasingly—but certainly not completely—in tune with this modern moderation. It’s a somewhat ironic twist, of course—after spending the first half of my life cheerfully wrecking my self, I’ve dedicated the second half to damage control and careful restoration. Like a classic car lovingly restored after years of reckless handling, my body is demanding a new approach—one grounded much more in “self compassion” rather than unbridled indulgence.

There is wisdom in that ancient saying that I heard somewhere, “Even if you faithfully follow the teachings, neglecting self-care will prevent you from mastering your art.” The relevance of this wisdom becomes clearer with age and accumulated injuries. Budo, after all, is a physically demanding pursuit with no retirement. Hours spent training indoors, frequently in poorly ventilated gyms, with equipment that gathers sweat, dust, and other unmentionable gunk, make health and hygiene essential concerns. Add to that the unforgiving nature of training, and you quickly realize that treating your body like an afterthought is simply not sustainable.

I mean, in my day we weren’t even allowed to drink water during keiko! Training on an injury? Hell yes! A recovery day? Hell no! It might build mental toughness and resilience—the old budo konjo thing—but from a sports science perspective, nay, a common-sense perspective, it is absurd, borderline criminal. And as for the forced drinking in budo clubs, there’s a word for that in Japanese now: Aru-hara (alcohol harassment), and you actually get into serious trouble for perpetrating it. Oh, how times have changed!

A relic from a time when endurance was prized over hydration, and passing out on the sports field was considered character-building. Kendo in summer was a literal hell, and to this day, rehydration in the dojo is kind of frowned upon among older generations.

And yet, lest I sound too much like a reformed sinner preaching abstinence, the convivial spirit of the Dai-ni Dojo still holds undeniable charm. It remains one of the great joys of budo life—though perhaps tempered now by maturity and a [usually] more judicious approach to alcohol. The conversations are still vibrant, the camaraderie still infectious, but the drinks these days are as likely to be ginger ale or non-alcoholic beverages as beer or sake. This isn’t a betrayal of tradition but a thoughtful evolution of it, recognizing that true budo excellence requires health as much as heart.

Indeed, the joy of post-training camaraderie doesn’t diminish with moderation; if anything, it’s sharpened by it. Clearer heads and healthier bodies lead to richer, more meaningful exchanges about budo, the universe, and everything. It becomes apparent that the true value of the Dai-ni Dojo isn’t the alcohol, but the opportunity it provides to reflect, share, and learn in an atmosphere of relaxed authenticity. Teetotallers, of course, have known this all along!

So, while I occasionally look back wistfully at those wild nights of my student days, not to mention instances of boozy buffoonery well into my ‘mature’ years, there’s no denying that moderation has its virtues. I’m grateful for the youthful indiscretions—after all, they make for excellent stories—but even more thankful for the chance to approach my training and social life with a healthier respect for body and mind.

Ultimately, martial arts shouldn’t always be about extremes—neither too much rigid asceticism nor epicurean self-sabotage. They’re about balance. The samurai of old knew this, even if they didn’t always practice it perfectly. Today’s younger generation seems to grasp it instinctively, perhaps benefiting from the hindsight of their elders’ misadventures.

As for myself, I happily embrace this new balanced chapter. After all, I’ve given my body plenty of reason to protest over the years—now it deserves my attention and care. The second half of my budo journey may be about repairing some of the damage done, but it’s a joyful task. After all, I’ve still got plenty more Dai-ni Dojo sessions left to enjoy—just with fewer headaches the next morning.

And may I say, cheers to that!

[1] Yoshida Seiken, Seiden Tsukahara Bokuden (Takada Shoin, 1943). p. 163

[2] Furukawa Tetsushi, Budō Shoshinshū (Iwanami Bunko, 1943) pp. 29-32

No comments yet.