Budo Beat 46: Three Angles, One Truth

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

Last week I went to Hong Kong, where we held the first Asia Oceania Shinpan Seminar. It also doubled as the kick-off meeting for the brand-new Asia Oceania Kendo Federation, which will host the inaugural Asia Oceania Kendo Championships at the Tokyo Budokan in May 2026. A historic step. Being present at the meeting on behalf of the New Zealand Kendo Federation, along with our exalted chairperson Sue Lytollis, felt like watching the gears of something long overdue finally begin to turn. After the meeting, our attention shifted to the seminar. Shinpan. A referee seminar, yes, but also an examination to select candidates for the AOKC next year. The pressure was real. I am usually the interpreter at these sorts of events, shuttling between languages while everyone else does the actual work, but this time I was thrown into the mix as one of the participants, flags in hand and nowhere to hide.

We had two solid days of refereeing practice with shiai-sha (competitors) from Hong Kong and China. For reasons that remain a mystery to me, there was an exceptionally high rate of Nito versus Jodan bouts (Nito being the two-sword style, Jodan the high-stance single-sword style). Very irregular in most events, but evidently not so in Hong Kong!

As soon as the first matches began, I was reminded that refereeing should not be some optional volunteer task. It is the backbone of fair competition and, more broadly, a quiet engine of kendo’s development. We all have a responsibility to learn and to strive to excel at shinpan. The newly appointed President of the Asia Oceania Kendo Federation, Hanshi 8th Dan Makita Minoru, said in his opening address, “If refereeing improves, shiai improves, and if shiai improves, kendo improves…” Simple, but absolutely true. When the referee cannot do their job, everything collapses. Bad calls deform understanding. Confused decisions produce confused kendoka. But firm, fair, accurate judgement encourages the right posture, intention, and proactive kendo. It makes things right. A good referee does not control the match. A good referee protects its meaning.

An outline of the expectations. Get it right.

Two booklets that every shinpan should have in their bags are the “FIK Regulations of Kendo Shiai and Shinpan” and the “Handbook for Kendo Shiai and Shinpan Management”. A little-known fact, I actually translated both of these documents in my capacity as International Committee member for the All-Japan Kendo Federation. You can download them by clicking on the graphics below. Don’t leave home without them!

Shinpan require special skills. Not just the knowledge you learn from reading the rulebook, although you should do that as well, but those earned through years of dedicated training and actual refereeing. A shinpan must be a grown-up in the proper sense. Calm when things get messy. Alert when the flow is subdued. Humble enough to know that unconscious bias or inexperience can ruin a match for everyone. You take each match as seriously as the shiai-sha.

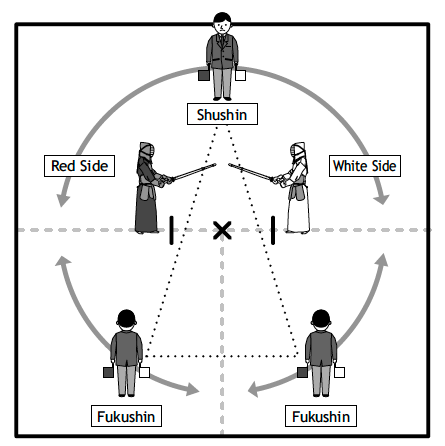

We kept circling back to the idea that the referee is part of the match, but at the same time, should NOT be a part of the match. The competitors have their kamae (fighting stances). The referee also has one. Shoulders relaxed. Eyes open. Steps clean and efficient. No drifting away from the protagonists, but no chasing either. Definitely no twirling the flags like a weekend matador. Even the angle at which you raise your arm matters. A sharp, clean signal shows conviction. A wobbly one broadcasts confusion. And confusion spreads.

We were also told on numerous occasions that “when in doubt, refer to Article 1 of the rules”:

“The purpose of the ‘Regulations’ is to get shiai-shato compete fairly in shiaiof the INTERNATIONAL KENDO FEDERATION (FIK), in accordance with the principles of the sword, and to properly referee the shiai without prejudice.”

When the three-referee system is working well, it looks almost simple. Three people, three angles, one truth. When it is not working well, it looks like three unrelated individuals auditioning for different performances. That is why mutual trust is vital, and why aiki, the synchronicity of intent, matters.

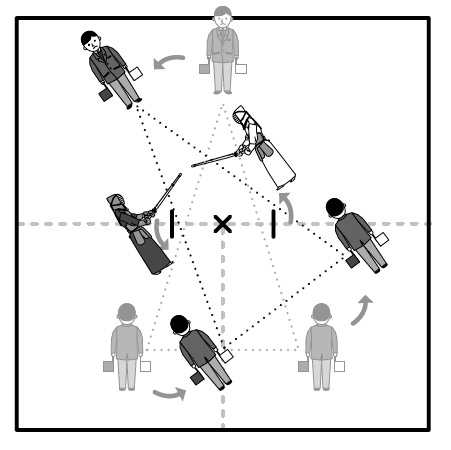

You never anticipate the point, but you must anticipate the movement of the shiai-sha. Read ahead and get yourself in the best possible position to see clearly. Easier said than done. The harmonised movement of three shinpan in the isosceles triangle formation must evolve with the manoeuvres of the shiai-sha, yet remain solid enough that both competitors can be seen from three different angles with no blind spots. You must also keep the other shinpan in your peripheral vision so you can respond to their calls. This is the classic teaching known as enzan-no-metsuke, maintaining a soft, expansive gaze like watching a distant mountain. You do not stare at one point. You take in the whole field, including your fellow referees, without losing focus on the action in front of you.

You only get one chance to make the correct decision. There are no video replays in kendo. Just three sets of naked eyes making calls in real time amid flurries of frenetic attacks. Your job as shinpan is to be in the right place at the right time to make the right call. It did not make our jobs easier when some of the supercharged shiai-sha essentially sprinted the equivalent of a marathon inside the shiai-jo like two combatting spinning tops. “Adjudicating 8th Dan matches would be so much easier,” I thought. At least they stay still most of the time and usually score when they do move.

The instructor’s whistle stopped us in our tracks as we replayed situations, nodded a little, and once again questioned why anybody would want to do this job. Get it wrong and you get an earful. Get it right and nobody says a word. Silence is golden.

What impressed me most about the seminar was the humility of the participants. Everyone understood that refereeing is not something you stroll into and magically master. You get good the same way you do in kendo itself. By watching carefully. By stuffing things up. By being corrected. By trying again. By realising you have barely scratched the surface. Even senior referees in Japan meet regularly for this kind of study, and I have seen more than one 8th Dan receive a well-deserved bollocking for a missed call. Nobody is above the learning curve.

That humility is one of the unspoken pillars of being a referee. It is not about strutting around like some big swinging dick. Or at least it shouldn’t be. It is about taking responsibility for the match, for the competitors, and for the spirit of kendo itself.

As we prepare for the first Asia Oceania Championships in 2026, refereeing will play a decisive role in shaping how the region’s kendo matures. This is true everywhere, as Makita-sensei noted at the outset. Competitors will train hard, but referees define the meaning of success. That is the quiet beauty of shinpan work. It is also the immense weight. When it is done well, nobody notices. When it is done poorly, everybody does. And the footage will be online forever for the trolls to devour.

I’m committed to keeping my work freely accessible to all budo enthusiasts, wherever they are. If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve found here and would like to support my ongoing efforts and projects, “buying me a coffee” (beer actually), or my books, would make a world of difference. Cheers!

The influence of the shinpan goes far beyond awarding ippon. Referees are quiet teachers. Every decision nudges competitors toward a clearer understanding of kendo. Clear judgement teaches clarity. A firm call teaches resolve. Consistency teaches trust. And the absence of ego teaches something even more precious in a martial art where ego is always waiting to pounce. That is why I think doing shinpan is a rite of passage in kendo. Criticising from the sidelines or over a keyboard is too easy. Picking up the flags is not.

Refereeing is demanding. It requires patience, honesty, and the courage to stay calm when things get tough. We often talk about the development of kendo in terms of competitors, teachers, or technical achievements. But behind every strong competitor is someone who has been adjudicated fairly. Behind every fair judgement is a shinpan who has taken the role seriously. And behind that seriousness is the shared belief that kendo deserves our best effort. Shinpan do get it wrong sometimes. It is not ideal, but it provides a learning experience for everyone. Just bloody deal with it.

When I played soccer as a boy, the usual snipe at the volunteer umpire was “Jeez ref, are your freaking eyes painted on?!” I cringe at how disrespectful we were, and it still grates on me when I see athletes haranguing referees in any sport like spoiled brats. Rugby is a great sport in this sense. The wrong call is made, but the players do not carry on like porkchops. They simply get back to the job of winning the match.

Maybe that is why refereeing has become more meaningful to me as I have got older. You begin to realise that the people holding the flags or the whistle are not obstacles to overcome, but quiet custodians of whatever game you love. Without them, the whole thing collapses into noise and bluster. With them, there is shape, purpose, and a standard we can all aspire to.

Not many sportspeople have the opportunity to referee their own discipline. We do in kendo, and I believe that is integral to personal development. It forces you to stand where judgement is made, to feel the weight of fairness on your own shoulders, and to understand that respect is not something shouted from the sideline. It is something you practise, one call at a time. And every time you do it, you reveal something about your understanding of kendo itself.

Postscript: One topic that stirred a considerable amount of discussion (confusion) was the post-COVID handling of tsubazeriai, the close-quarters clinch where the tsuba end up welded together. It is an important issue, and it deserves its own Budo Beat article. I will tackle where things stand with tsubazeriai in the next instalment. It won’t be of much interest to non-kendoka, but it needs to be done. Next time.

No comments yet.