Budo Beat 5: Finding Life in the Shadow of Death

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

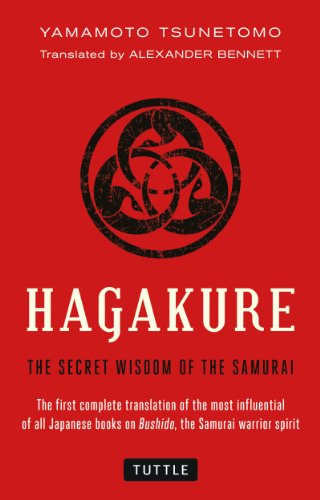

There’s this book I can’t stop thinking about. I mean, really thinking about. It wasn’t always like this. In fact, I used to loathe it. But fate, in one of its more whimsical turns, brought us together. Several years ago, I found myself bound by contract to translate it for Tuttle. And at first, let me tell you, it was nothing short of a trial. A relentless, teeth-gritting exercise in frustration. It didn’t make sense—so much of it seemed utterly lost in translation. It felt as though the very structure of the thing was conspiring against me.

I tried and I tried, but it was like paddling upstream in a murky river. Nothing seemed to stick. But then—out of nowhere—something happened. A peculiar series of dreams, clearly spurred by stress, broke into my slumber. They were most peculiar. A cantankerous old Japanese geezer—Yamamoto Jōchō, he called himself—waltzed right into my dream, rude as anything, and began belittling me for the mess I was making of his words. He mocked me mercilessly for my clumsy translation, as if I were some bumbling fool.

Now, I don’t want to get bogged down in the weirdness of it all—because it was truly bizarre—but these ‘little’ intrusions in my psyche every night set the stage for a revelation. A shift in the way I approached the book. Instead of trying to force Jōchō’s words into neat little boxes of translation, I decided to listen. Really listen. As if I were sitting at the feet of my budo teachers, hearing their rambling, disjointed thoughts. I just let it all wash over me. And with that new mindset, something changed. I started to read between the lines—no longer just translating the words, but feeling their pulse, their rhythm. I began to appreciate the book for what it truly is—a treasure, raw and unrefined.

So, what book am I talking about, you ask? I’m sure most of you have already figured it out. Hagakure.

Hagakure, meaning “Hidden by Leaves,” has gained near-mythic status as a misunderstood gospel on ‘bushido’, the samurai’s code. Completed in 1716, it unfolds across 11 books with over 1,300 vignettes and musings that bring to life the Saga (Nabeshima) domain’s spirit in Kyushu. The first two books capture the thoughts of Yamamoto Jōchō, a mid-level samurai devoted to Lord Nabeshima Mitsushige, recorded by his fellow clansman Tashiro Tsuramoto. Later sections dive into the tales of the Nabeshima clan, critiques of rival samurai, and a gallery of samurai life.

The passages vary in intensity and clarity. Some are short, slicing through ambiguity with a clean edge, while others are tangled, hard to untwine without grasping the era’s unique, peace-time dilemmas for samurai. Hagakure exposes the raw, conflicted life of a Nabeshima retainer, celebrating his victories and grappling with the elusive principles of honour and loyalty.

This is no romantic tale—it’s gritty, at times violent, even sensual, as it reveals the fierce devotion of warriors for their lords, what Jōchō (Tsunetomo) calls a “hidden love,” a loyalty that’s much more than an oath. Jōchō’s passion for his lord was so all-consuming he wished to die alongside him, though the practice of junshi (ritual suicide to follow one’s lord in death) was by then banned. So, he retreated to the life of a monk, where, in solitude, Tsuramoto recorded his testament over about a decade.

Reading Hagakure is like riding a rollercoaster through the essence/madness of a samurai—reflective passages give way to passionate rants about the warrior’s ideal frame of mind. Rather than a tidy lecture on ‘bushido’, the text plunges readers into an emotional whirlpool that veers between dark depths and moments of serenity. Look close, and there’s even a sly grin here and there, a humour so dry it might slip by unnoticed. 😉

The most famous line, “The way of the warrior is to be found in dying,” hits the book’s central chord: a warrior’s ultimate duty is absolute loyalty, even at the cost of life. During World War II, this line resonated in the ears of kamikaze pilots, many of whom clutched copies of Hagakure as they soared towards certain death. I know this for a fact as I talked with Odachi Kazuo-sensei about the book, and he admitted he had his own copy in his flying jacket pocket ready to get himself in the right frame of mind to die.

After the war, the book faced harsh judgment for promoting extreme sacrifice, cast as a blueprint for militaristic fanaticism that urged young men toward oblivion in service to emperor and country.

But is that really all there is to it? My years translating Hagakure unveiled a deeper dimension. Jōchō’s obsession with death was not simply about courting the end but rather a path to a richer life. My approach was to read his words in their own historical light, without trying to twist them into a modern shape. Through its contradictions, Hagakure reveals a worldview where life and death aren’t opposites but interwoven. Jōchō’s paradox is this: only by embracing death can a warrior truly live, free from ego and all its snares, and, in doing so, find genuine purpose.

If you’re looking for a straightforward guide to strategy like Musashi’s Book of Five Rings, you won’t find it in Hagakure. Nor will it double as a manual for martial techniques. What it does offer, however, is something much more elusive—a window into the samurai soul. It shines a flickering light on the values that shaped these warriors, unravelling in many ways the very essence of Japanese martial arts.

Now, I’m well aware of the “bushido never existed—it’s all a myth” crowd. They’ll scoff at such sentiment, and frankly, I couldn’t care less. Now and then, I’ll write up a few articles to make my case—articles on things like sutemi, zanshin, and other concepts important to budo that can be traced so neatly within the pages of Hagakure.

In any case, it’s not the sort of book that promises world-shattering wisdom, but it does ask something far more profound: to confront your own mortality head-on, to face the fleeting nature of life without flinching. That was the main message for the samurai warriors it was actually written for.

Beneath its contradictions, Hagakure holds a fundamental truth. The paradox at its heart is simple yet profound: only by coming to terms with the certainty of death—both in thought and in spirit—can we find meaning and depth that makes life worth living. Let’s simplify that. Life is too bloody precious a thing to waste, and there’s nothing like a taste of death to make you realise what you’ve got.

I still have a massive amount of Hagakure content that I’ve never published. Over time, I’ll toss a few pieces your way in this blog. It’s all there—just waiting to be uncovered.

No comments yet.