Budo Beat 6: “Miyamoto Musashi” – The Epic Gets a New Suit of English Armour

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

I’ve just put the finishing touches on my translation of Yoshikawa Eiji’s prewar epic, Miyamoto Musashi, which explains my recent absence from these pages. Six years—yes, six—have brought me to this point, and my final task was writing an introduction, which ballooned into a work almost worthy of its own ISBN. The novel itself spans 1,800 pages, and Tuttle plans to publish it as three substantial volumes in June 2025. For now, I’m completely Musashi’d out, but I thought I’d share my introduction, if only to assure you I haven’t been spending all my time contemplating clouds.

Introduction

The Author

Yoshikawa Eiji’s novel, Miyamoto Musashi, is so thoroughly seeped into the cultural consciousness that many now accept it as the definitive account of Japan’s most celebrated swordsman. Yet even Yoshikawa, for all his brilliance, readily admitted that the historical Musashi (1582?–1645) is more shadow than substance—a life distilled down to “60 or 70 lines of printed text.” What Yoshikawa conjured wasn’t so much a biography as a masterstroke of imagination, filling the gaps with such persuasive creativity that it’s almost impossible not to believe.

For those chasing the elusive ‘real’ Musashi—if such a figure can ever truly be pinned down—I’d point you toward Complete Musashi: The Book of Five Rings and Other Works, a project I was fortunate enough to bring to fruition in 2019 with Tuttle. It brings together Musashi’s own writings and the latest academic inquiries to present a more grounded portrait of his life and career. Thankfully, with the insights of modern scholarship, his life now amounts to far more than just 60 or 70 lines.

Having said that, although Yoshikawa Eiji’s novel Miyamoto Musashi is largely a work of fiction, it is also underpinned by extensive research and careful attention to historical detail. Yoshikawa combed through a vast array of old documents, records, and past accounts to construct a world that felt authentic and to breathe life into his characters. His deep commitment to capturing the culture, environment, and spirit of Musashi’s era shines through in the narrative’s rich detail—from social hierarchies and political intrigue to the nuances of religious life, and even the technical and psychological complexities of swordsmanship.

While he supplemented the missing parts with an abundance of poetic license, Yoshikawa’s research ensured that his portrayal of Musashi and the surrounding cast combined historical plausibility with dramatic vitality, creating characters that felt both authentic and compelling.

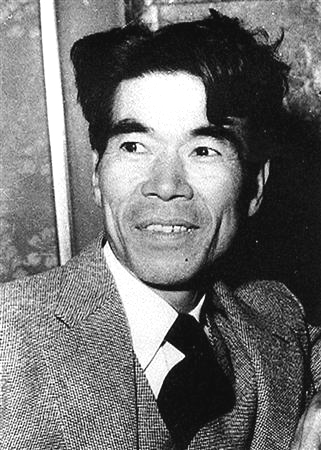

Born Yoshikawa Hidetsugu (1892–1962) in what is now Yokohama, Yoshikawa’s early life was anything but promising. His father, Yoshikawa Naohiro, was a former samurai of the Odawara domain. During the Meiji era, when samurai no longer existed as a class, Naohiro faced a series of calamitous business failures that, combined with a stint in prison, sent the family’s fortunes into a steep decline.

Forced to leave school at the age of 11 to help support his family, young Hidetsugu’s future seemed bleak. At 18, a near-fatal fall at the Yokohama docks spurred him to leave for Tokyo, where he found work as an apprentice in a lacquerware workshop. It was there, amidst the toxic lacquer fumes, that he discovered a love for senryū poetry and began writing under the penname “Kijirō.” While haiku is often associated with beauty and depth, senryū leans toward the playful, highlighting the quirks and absurdities of human behavior. This influence can be seen throughout his later novels, including this one.

In 1914, his first literary break came with The Tale of Enoshima, which won acclaim at a Kodansha-sponsored writing contest. This prompted a pivot to journalism where he found his footing in the corridors of the Maiyū Shinbun newspaper. The Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, devastating as it was, sparked a resolve in him to make writing his life’s work. And write he did, first under a carousel of pseudonyms, before deciding on “Yoshikawa Eiji.”

His serialized Secret Scrolls of Naruto in the Osaka Mainichi Shinbun in 1926 soon made his name indispensable on bestseller lists. By the mid-1930s, Yoshikawa turned his hand completely to historical fiction, hitting a commercial home run with Miyamoto Musashi. The Second Sino-Japanese War saw Yoshikawa don a journalist’s hat once more, traveling to the front lines in 1938 and penning patriotic missives about the war effort as a member of the government-sponsored “Pen Corps.” This was a time when he dabbled in Sinophilia, penning in 1939 Romance of the Three Kingdoms among other celebrated works.

After the war, he stepped away from writing, apparently overwhelmed by the shock of defeat and going through a period of depression. His friend and fellow writer Kikuchi Kan, however, encouraged him to return to his craft in 1947. This led to the creation of postwar masterpieces such as The Heike Story: A Modern Translation of the Classic Tale of Love and War (translation published by Tuttle in 1981 and 2002), among many others.

By the time of his death in 1962, Yoshikawa had firmly established himself as one of Japan’s eminent literary geniuses. Highlighting the extraordinary scope of his work, Kodansha, a leading Japanese publisher, released an 161-volume collection titled Yoshikawa Eiji Bunko in 1975 (available only in Japanese), testament to the incredible breadth of his output. His productivity was nothing short of astounding.

The Novel

The book you hold is a benchmark of Japanese historical fiction, originally serialized in the Asahi Shinbun from August 23, 1935, to July 11, 1939. Written during a tempestuous period spanning the Sino-Japanese War and the approach of the Pacific War, it captivated readers and became a cultural pillar in a Japan increasingly shaped by rising nationalism and militarism. It was for this reason that, in the postwar period, GHQ required that certain jingoistic terms and passages be purged from the book before republication.

The novel’s origins lie in a spirited ‘duel’ in 1933 between two prominent literary figures, Kikuchi Kan (1888–1948) and Naoki Sanjūgo (1891–1934), over the authenticity of Musashi’s perceived greatness. Naoki stirred controversy by arguing that, despite Musashi’s image as a swordsman nonpareil, he was, in reality, not particularly strong. Bold claims indeed—especially when weighed against Musashi’s own words in the introduction to The Book of Five Rings.

“I have devoted myself to studying the discipline of combat strategy since I was young. I experienced my first mortal contest at thirteen when I struck down an adherent of the Shintō-ryū named Arima Kihei. At sixteen, I defeated a strong warrior named Akiyama from the province of Tajima. At twenty-one, I ventured to the capital [Kyoto] where I encountered many of the best swordsmen in the realm. Facing off in numerous life-and-death matches, I never once failed to seize victory. Afterward, I trekked through the provinces to challenge swordsmen of various systems and remained undefeated in over sixty contests. This all took place between the ages of thirteen and twenty-eight or -nine.” (Bennett, Complete Musashi, pp. 59-60).

Naoki contended that Musashi’s opponents were neither particularly skilled nor well-known. He argued that Musashi deliberately avoided duels with prominent swordsmen of the Kantō region, instead concentrating his activities in western Japan, where his reputation wasn’t nearly as solid as he claimed. Central to Naoki’s argument was the lack of evidence identifying most of the individuals Musashi supposedly faced in his 60 life-or-death duels. This absence of documentation, Naoki suggested, implied that these opponents were essentially nobodies, and that Musashi was certainly no “master swordsman.”

He presented his argument during a gathering of literati, where he debated the point with Kikuchi Kan, the founder of the popular monthly magazine Bungei Shunjū. Kikuchi staunchly defended the legend, asserting that Musashi was undeniably Japan’s most awe-inspiring swordsman and that his reputation was well deserved. Yoshikawa Eiji was also in attendance. Turning to him, Naoki asked, “What say you, Yoshikawa?”

Yoshikawa sided with Kikuchi. In response, Naoki published an article in Bungei Shunjū, challenging Yoshikawa to defend his position. However, Yoshikawa remained silent—until 1935 that is, when he released his first instalments of Miyamoto Musashi. The novel’s success was unprecedented. Its serialization was so popular that it was read aloud on the wireless by the famous film actor and raconteur Tokugawa Musei. It inspired numerous film adaptations and cemented the widespread belief that Musashi was, without question, the greatest samurai swordsman of all time. Thus, the debate was effectively settled in the court of popular opinion.

Incidentally, in the same year, Kikuchi Kan proposed naming an award for popular fiction after Naoki Sanjūgo who had died the previous year, still waiting for Yoshikawa’s riposte. This became the Naoki Prize, which, alongside the Akutagawa Prize for promising new authors, remains one of Japan’s most prestigious honors for writers.

The novel’s influence is difficult to overstate. It became the foundation for an entire genre of Musashi adaptations—films, television dramas, manga, and even video games owe their portrayals of Musashi to Yoshikawa’s vision. While rooted in historical themes, the book is ultimately a sweeping reimagining of Musashi as a warrior-philosopher—impossibly strong and profoundly wise. This idealized Musashi has, for better or worse, overshadowed the historical figure in the public’s mind. Yoshikawa himself seemed to struggle with this legacy, fully aware that his portrayal drew more from the allure of fiction than the limitations of historical fact.

Miyamoto Musashi brims with a cast of unforgettable characters, each contributing in their own way to Musashi’s evolution. Takuan, the sharp-tongued Zen monk, challenges Musashi to look beyond swordsmanship and grapple with the deeper spiritual meaning of his place in the universe. Otsū, steadfast in her devotion, provides a tempting, and often prodigiously emotional touchstone of love and loyalty amidst Musashi’s often lonely, inhuman path. Iori, the young disciple, highlights Musashi’s journey from a self-centered rōnin answerable to nobody, to a mentor capable of making a lasting contribution to the greater good of humanity.

On the opposite side of the spectrum is Sasaki Kojirō, the dashing yet ruthless antihero whose own ambitions serve as a foil to Musashi’s pursuit of enlightenment. Then there’s bumbling Matahachi, Musashi’s childhood friend, whose repeated moral failings offer a cautionary tale of squandered potential, and his scheming mother, Osugi, whose manipulations ripple throughout the story.

Along the way, Musashi encounters a wide array of savory and unsavory figures, from humble farmers to the patricians of Kyoto, aspiring martial artists to cunning rogues and power-hungry lords. Each character, whether ally or adversary, tests, shapes, or reflects some aspect of Musashi’s development, creating a plush tapestry of personalities that bring the story to life while driving the central theme of strengths and weaknesses in the human condition.

Known widely for his distinctive “two-sword” style, Miyamoto Musashi was already a famous, some would say infamous, figure for centuries in Japan, fêted as a paragon of martial skill, strategy, artistry and philosophy. By framing Musashi’s life as a treacherous journey of self-discovery, Yoshikawa deepened his cultural significance, turning him into an enduring symbol of youthful vigor, martial virtue, and spiritual awareness. The pragmatist embodied ideals that resonated with the times. The storyline’s focus on his progress from a devilish wild child called Takezō, to a salient existentialist warrior-philosopher struck a chord, and it was a portrayal that made samurai chic. In a time of upheaval, readers drew solace and inspiration from the notion that meaningful transformation was possible, even in—or perhaps because of—times of great adversity.

The Legacy

Yoshikawa’s Musashi elevated the historical swordsman into an enduring symbol of the samurai mind, weaving together many different elements to capture the essence of “bushido”—the “Way of the samurai.” Through Musashi’s journey, Yoshikawa defined the ideals of this Way as a flagellant pursuit of self-mastery, weaving together the deadly techniques of combat and the sage insights of Buddhist philosophy.

Musashi emerges not only as a brilliant swordsman but as a seeker of a higher spiritual plain, embodying virtues such as honor, humility, introspection, and resilience. Yet, when circumstances demand, he is able to unleash a chilling and decisive brand of violence, wielding his devastating skills unflinchingly with lethal precision. This portrayal connected deeply with wartime readers, offering a model of stoic tenacity that both inspired and consoled in times of uncertainty. He came to be seen as a virtual superhero in the eyes of the public.

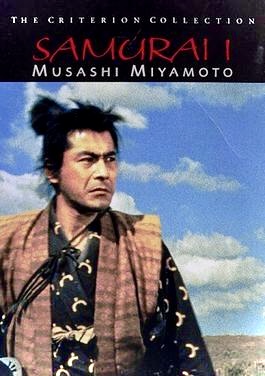

Culturally, Miyamoto Musashi became foundational to the modern understanding of the samurai ethos, surpassing literature to influence film, theater, manga, and even modern martial arts. The novel inspired countless adaptations, most notably, in my mind, Inagaki Hiroshi’s iconic film trilogy (1954-56) starring Mifune Toshirō, which brought Musashi’s story to a global audience. The first in the trilogy, Samurai I: Miyamoto Musashi, received a Special Award at the 1955 Academy Awards for outstanding foreign language film. Even today, echoes of Yoshikawa’s Musashi reverberate in pop culture, from Inoue Takehiko’s celebrated manga series Vagabond to video games and anime that perpetuate the lone warrior archetype.

At the same time, the novel reflects the constraints and rhythms of its serialized format. Written over four years for a newspaper readership, it was crafted to be consumed in short installments, often requiring reintroductions of key plot points, characters, or conflicts to accommodate readers who might miss previous sections. This structure contributes to a sense of repetition, as Musashi’s struggles, training, and interactions are revisited throughout the narrative.

This repetitiveness, however, is deeply tied to the novel’s core themes—personal actualization, the pursuit of enlightenment, and the cultivation of martial skill and inner strength. Yoshikawa uses this cyclical pattern of training, confrontation, and reflection to mirror Musashi’s relentless search for perfection. While this structure can create a feeling of déjà vu for readers approaching the work in a single reading, it also underscores the incremental nature of Musashi’s passage.

Supporting characters and their recurring roles further contribute to this dynamic. Yet, these repetitions serve a purpose: they highlight Musashi’s unwavering commitment to his path, contrasting his improvement against the stagnation and foibles of others and emphasizing the plodding nature of transformation. Far from being a flaw, this rhythm becomes an integral part of the novel’s enduring appeal.

Moreover, at times the novel feels almost like a travel guide, with Musashi’s trek through Japan unfolding in such vivid detail and at such length that it’s as if the reader is traveling alongside him in real time! The novel’s sheer scope turns each stop along the way into an event. Many of the small villages and locations where Musashi’s adventures take place exist today, and the locals still take pride in their connection to the story.

For example, I visited the hamlet of Yagyū in Nara a couple of months ago, which features in the novel as the home of Sekishūsai, a renowned swordsman and one of Musashi’s contemporaries. While showing me around, an elderly gentleman mentioned how Yoshikawa’s glowing portrayal of their village “sparked quite a tourism boom back in the day,” and even swayed the All-Japan Kendo Federation to fund the construction of a large dojo there—a fitting tribute to such a significant place in Japan’s rich swordsmanship history.

In essence, Miyamoto Musashi turned an enigmatic historical figure into a cultural icon of the modern era. The story’s themes and structure reflect the steady, incremental nature of personal transformation, ensuring its relevance across generations. It remains a landmark of samurai literature, inspiring countless works and keeping Musashi’s legacy well and truly alive.

The Translator

“One thousand days of training to forge; ten thousand days to polish. Yet a bout is decided in an instant.”

The words loomed large on the wall of my high school kendo club’s dojo, as constant and sharp as the clash of bamboo swords—a stark reminder that mastering the art of the sword was less a hobby and more a lifelong commitment. In 1987, I arrived in Japan, blissfully unaware of what lay ahead, expecting a fun-filled one-year exchange program. Somehow, through a mix of chance and fate, I found myself barefoot on a dojo floor, gripping a kendo practice sword and diving headfirst into a frenetic discipline I could barely make sense of. At the conclusion of each punishing session, drenched in sweat and utterly spent, my teammates and I would chant that cryptic verse in unison. Its meaning? Completely lost on me at the time, and honestly, I was usually too exhausted to think about it.

It wasn’t until much later that I learned those words came straight from The Book of Five Rings, the classic treatise by Miyamoto Musashi completed one week before his death in 1645. At the time, I had no idea who Musashi was or why his wisdom somehow seemed important enough to loom over me every day. That all began to shift when someone handed me a copy of Yoshikawa’s Miyamoto Musashi. What I thought would be a casual, if very lengthy, read about swashbuckling samurai turned out to be something far more impactful—like a bolt of lightning, sparking with all manner of revelations.

Yoshikawa’s storytelling gave form and meaning to the raw, bone-weary dedication I’d been grinding through on the dojo floor. Those endless, sweat-soaked hours of practice suddenly felt purposeful. The novel planted within me a seed—a romantic, perhaps even naive, belief in perseverance, discipline, and the obstinate quest for forging mind, body, and technique. What had once seemed like a baffling and punishing foreign exercise became something far grander: a baffling and punishing Way.

As such, what began as a one-off adventure abroad has stretched into a lifelong epic, the kind of outcome that makes one marvel at the bizarre twists in life. Nearly four decades later, I’m still in Japan, still walking the path of the sword—a path I might never have found without Musashi. But if I owe a debt to Musashi, it’s Yoshikawa Eiji who holds the lion’s share. His words didn’t just light the Way of the shugyōsha; they ignited something in me that’s burned ever since.

With these thoughts in mind, I chose to translate the entire novel rather than an abridged version. My goal was to preserve the richness and essence of a story that has touched readers for generations. This is more than just a tale; it’s a meaningful interpretation of Japan’s cultural and philosophical heritage, capturing the ideals of striving for excellence. Yoshikawa’s portrayal of Musashi and his journey reflects challenges and values that still resonate deeply. I hope this translation allows readers to feel the power of Yoshikawa’s storytelling and the enduring legacy of his depiction of Musashi, the greatest samurai swordsman of all time.

Alex Bennett

No comments yet.