Budo Beat 27: Gaping, Not Aping

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

I was waiting in line last Wednesday at training to fight my sensei. I thought I was first in line, but it turned out his dance card was already well and truly booked. Thirty minutes later… What a waste of good training time. NOT!

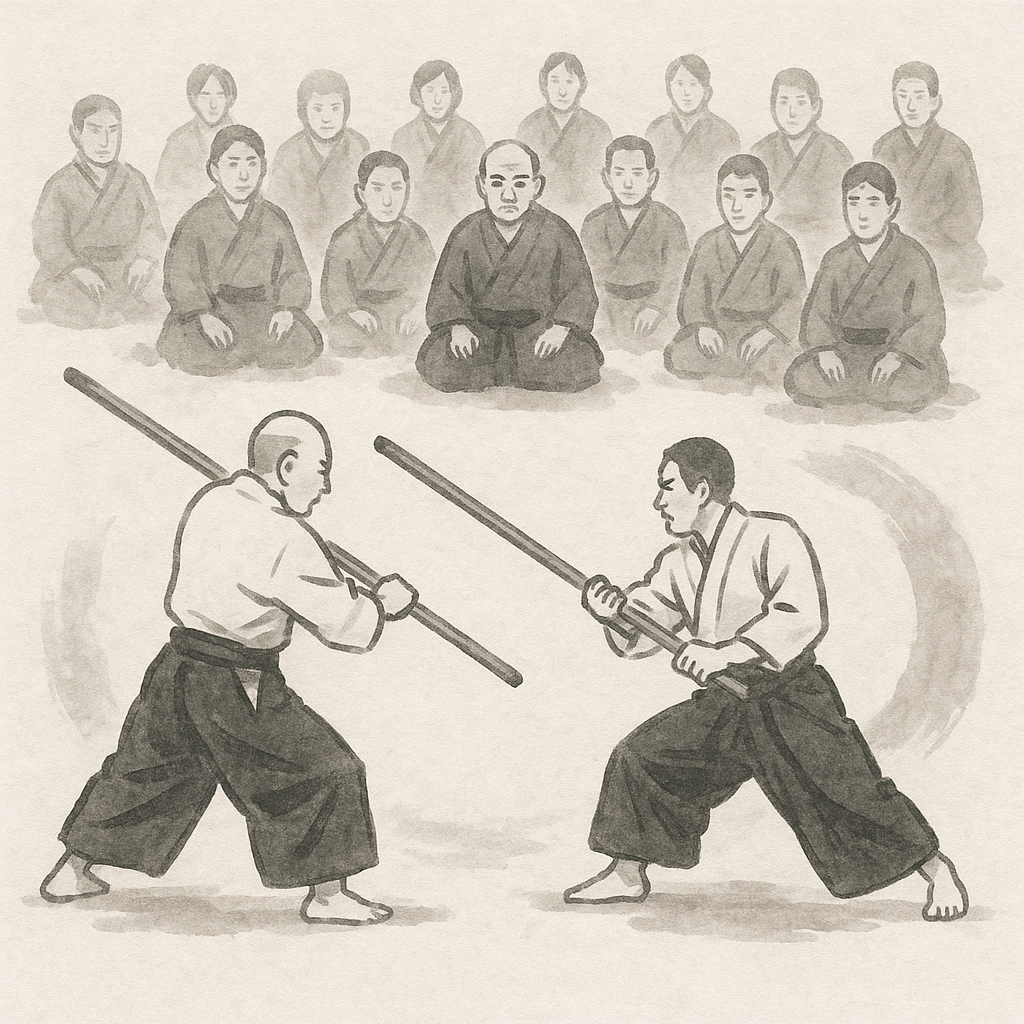

Mitori-geiko, that budo concept whose literal translation— ‘practice by watching’—undersells its complexity rather neatly, is essentially martial arts as serious armchair philosophy. You perch at the edge of the dojo, peering intently at two budoka smashing each other with vigorous intent, hoping by some osmosis of observation you’ll absorb the magic secret hidden in their technique. Yet, mitori-geiko isn’t mere passive spectating; it demands relentless mental engagement, an eagle-eyed scrutiny, and an acute knack for distinguishing genuine skill from flamboyant nonsense.

Everyone who steps into a dojo soon realises that no two martial artists move alike. Each person’s technique is riddled with quirks, strengths, weaknesses, and patterns. Watch a few rounds of any budo practice, and you’ll see this spectacle play out vividly. The trick (there’s always a trick) is figuring out what the heck to do with all this difference.

I love my old budo poems, and as one classic saying goes:

“Each has a different way of performing their techniques;

Observe carefully and learn from what others do.”1

This isn’t about slavishly mimicking someone else’s moves. If imitation alone were the key, we’d all achieve mastery after a single afternoon of watching some old samurai movies. Instead, the true benefit is gleaned from careful observation mixed with your own experimenting, and copious dollops of trial and error. Merely copying another person’s technique superficially, no matter who they are, won’t magically turn you into a budo prodigy. Watching others simply gives you useful hints about what’s possible, what’s effective, and just as importantly, what’s never going to work.

Mitori-geiko is a term for what amounts to paying attention while others sweat it out. But it isn’t just sitting back smugly, nodding like you have a clue. Genuine mitori-geiko demands sharp eyes, a curious and analytical mind, and the brutal honesty to confront your own embarrassing shortcomings.

Think of it like watching Roger Federer glide across a tennis court. Admiring his backhand doesn’t mean you’ll master it next weekend at your local club tournament. However, noting how he anticipates the ball, shifts his weight, or relaxes his grip just before hitting the ball could inspire improvements in your own game. Martial arts work the same way—it’s less about wholesale “aping” and more about “appropriating” useful little bits of technique to polish your own style.

Moreover, observational training is pointless without relentless effort in your own practice. Watching others without engaging deeply yourself is like sitting glued to cooking shows but never bothering to enter your own kitchen. Without sweat, reflection, and a healthy dose of frustration, none of those observed subtleties will stick. Notwithstanding, observation is invaluable—not just for improving your technical skills, but also for “polishing” your character and self-awareness. Another old poem sums it up rather neatly:

“Good or bad, your companions are mirrors:

Polish your spirit through observation.”2

A dojo isn’t just populated with students and teachers; it’s brimming with reflections of our own hidden traits, both admirable and aggravating. It’s easy, of course, to admire skilful strikes and graceful footwork, but it’s the irritations that often prove most instructive. When someone’s sloppy footwork gets under your skin, it might be worth considering if their clumsiness secretly mirrors your own. When a fellow student constantly rushes their techniques, ask yourself if you also fall prey to impatience. If another’s needless swagger makes your jaw tighten, perhaps it’s a gentle reminder about humility. Even something as small as irritation over a partner’s inability to keep up during instructions might reflect your own restless mind.

In short, when observing others in the dojo, you’re not just watching—you’re polishing. This means that observational training shouldn’t be a comfortable break. To reiterate, the genuine value of mitori-geiko isn’t only in identifying what others do superbly (although this is an important part of it); it’s in clearly spotting their errors, and consequently identifying your own.

There’s a temptation to envy someone else’s beautiful technique, wishing yours were a perfect match. But chasing after someone else’s exact form misses the whole point. Your technique will never be theirs—you’re built differently, think differently, and have faced entirely different training hurdles. Instead, your task is to distil the principles and processes you observe and apply them uniquely to your own context.

A celebrated budoka’s spectacular “Combo” might dazzle (Ryu’s ‘Shoryuken’ comes to mind), but it’s the unnoticed shifts in footwork, breathing, timing, or subtle grip adjustments moments earlier that contain the true magic. Spotting these finer (sometimes invisible) points and patterns will catapult your progress far beyond rehearsing big, theatrical moves in which you are oblivious to the undercurrents that drives it.

Over the years, I’ve trained myself to slow down and scrutinise others practising. I don’t just rejoice in witnessing outstanding techniques; I study their failures closely. What tiny lapse in focus or balance spoiled their move? What superfluous mechanical movement gave the game away? Identifying these minute errors or patterns has served to sharpen my own approach, and helped me identify similar issues in my own way of doing things.

That reminds me. Another invaluable form of mitori-geiko, perhaps less traditional but equally important, comes from watching myself on video. I guess you could call it “Me-tori-geiko”. Whenever I have the chance, I swallow my pride, and hit play—especially on the clips where I’ve royally stuffed things up. It’s astonishing, really, the yawning chasm between how I imagine myself moving and what’s actually unfolding on the screen. Techniques I thought razor-sharp look suspiciously like drunken ballet; moments I believed dignified seem closer to slapstick comedy. Occasionally, the cringe factor is so high I conclude that if I ever faced myself in combat, I’d gleefully and easily kick my own arse. There’s no denying the usefulness of this brutal self-examination; the camera, unlike the ego, never lies.

Next time you’re floorside in the dojo, don’t just sit passively admiring the spectacle. Engage with what you see. Observe intently, question constantly, and test your findings relentlessly. Even if lessons aren’t immediately obvious, they’re there, hiding in plain sight. Look, analyse, learn, absorb, plan, execute. I feel an acronym is in order: LALAPE…? A bit lame I suppose, and it ends with ‘ape’; but know that it’s so much more than just aping someone else or monkeying around. Ultimately, your goal isn’t becoming someone else’s shadow, but using their light to find your own way forward.

- “それぞれに 人の為す技 ちがふなり よく見て習へ 人のなす技” (Sorezore ni, hito no nasu waza ni, yoku mite narae. Hito no nasu waza.) Contained in Tomita Yoshinobu (ed.), Shiryō Nihon Kendō (Tomita Yoshinobu, 1982) p. 108 ↩︎

- “善きも友 悪しきも友の鏡なる 見るに心の年をみがけば” (Yoki mo tomo, ashiki mo tomono kagami naru. Miru ni kokoro no toshi [tsuki] wo migakeba…) This poem pops up in various froms and lengths in several books related to budo. For example in Ruijū Denki Dai-Nihonshi, Vol. 10 (Yūzankaku, 1936, p. 41), a fuller version reads:

“Good or bad, your companions are mirrors:

Polish your heart through observation.

If your mind settles into one place,

You’ll lose the resolve to progress.

Cast away the judgment of good and bad—

See clearly with an untroubled mind.

Always maintain the spirit

Of looking down upon your enemy. ↩︎

No comments yet.