Budo Beat 37: Bridging the Past, the Present, and the Pacific

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933) is one of those names you just can’t avoid if you spend any time talking about samurai. He is remembered as an educator, diplomat, and Quaker who became Under-Secretary General of the League of Nations! His life story is and career is just so phenomenal, there’s no way I can do it justice in this blogpost. (If you want to know a LOT more about the man, I suggest you check out the introduction in my book 😉

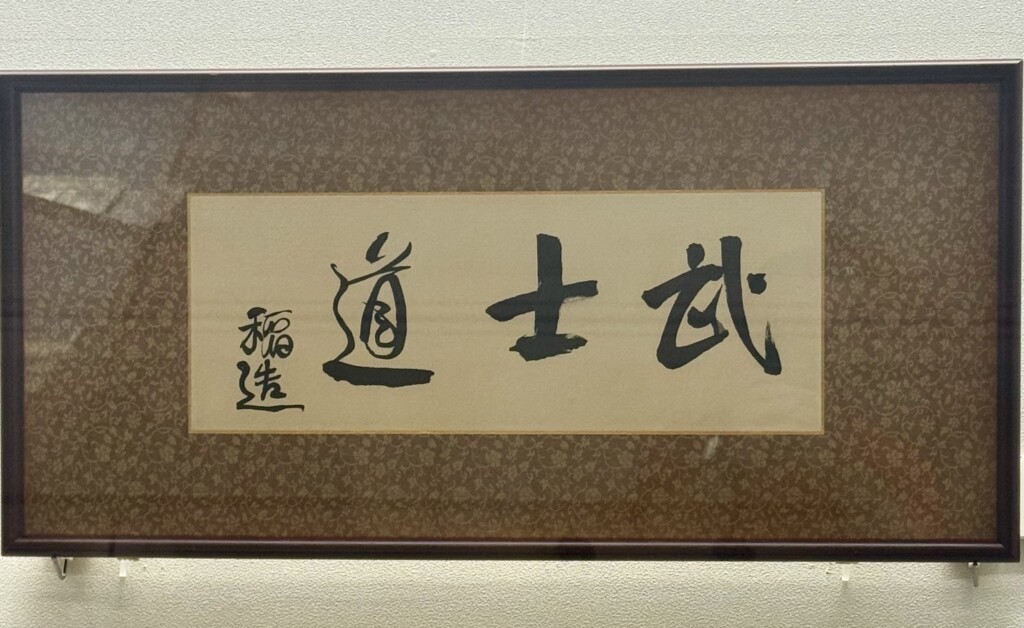

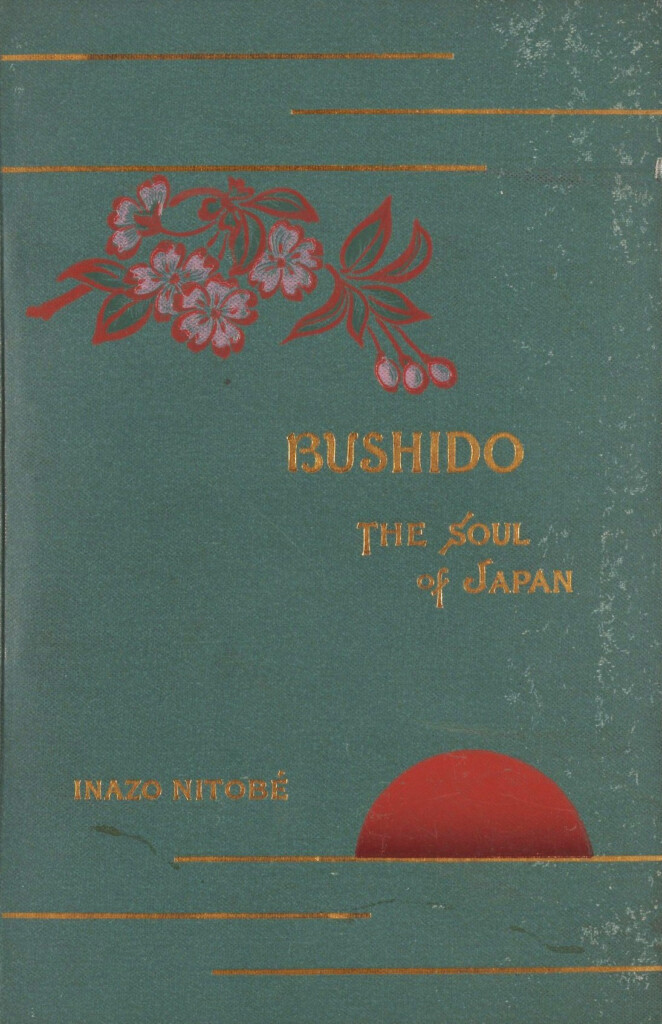

His lasting fame comes from a slim English book he published in 1900, Bushido: The Soul of Japan. He framed the samurai ethic around seven core virtues: gi (義 = rectitude), yū (勇 = courage), jin (仁 = benevolence), rei (礼 = politeness), makoto (誠 = sincerity), meiyo (名誉 = honour), and chūgi (忠義 = loyalty). He compared this moral framework to European chivalry and Christian ethics, presenting bushido as a universal code of character.

That book gave the world its most widely read version of the “samurai code”. It was translated into multiple languages, avidly read by Theodore Roosevelt, and remains in print today as an all time classic. Scholars are quick to call it out for what it is: romantic, historically shaky, and more Thomas Carlyle and Bible than Yamaga Sokō or Daidōji Yūzan. It is often dismissed in academia as hyped-up nonsense. Yes, ye olde bullshido… Notwithstanding, love it or hate it, Nitobe’s Bushido still matters because it continues to shape how people think about samurai ethics, in Japan and abroad.

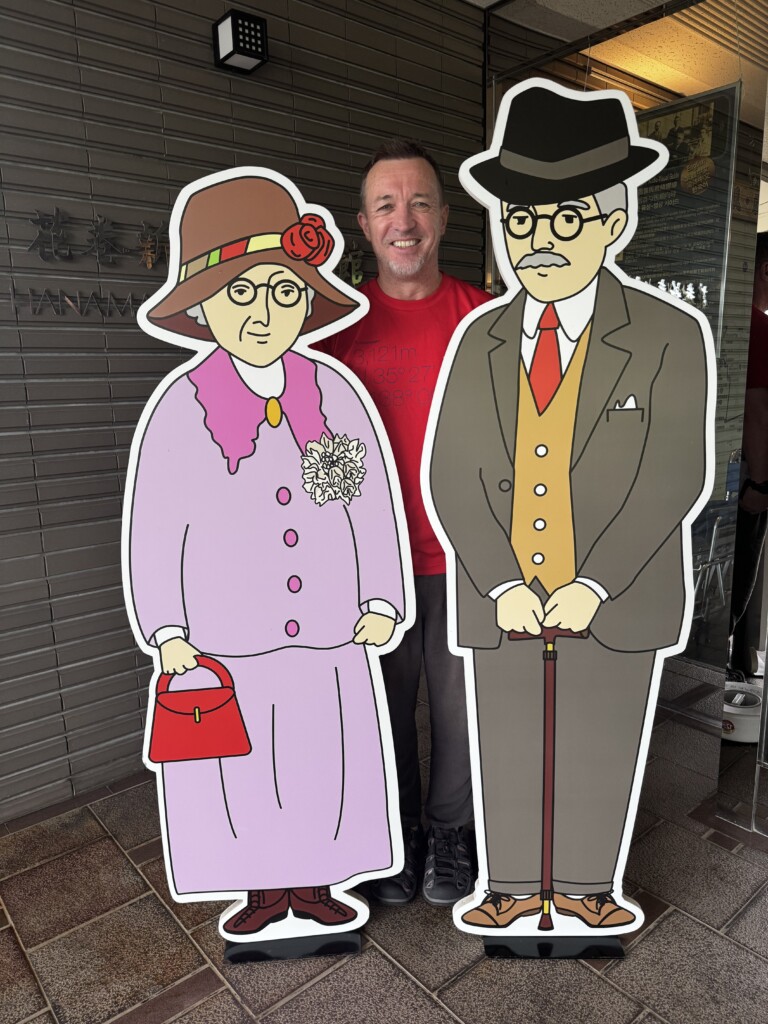

Anyway. Why Nitobe in this blogpost? I went up to Hanamaki last week following the yabusame in Morioka (Iwate Prefecture) and met up with my mate Jonathan Levine-Ogura. Monuments to Nitobe are found everywhere in Iwate, and Jonathan took me to see the Hanamaki Nitobe Memorial Museum not too far from where he lives. The museum lays out the Nitobe clan’s story in a way you can’t get from his book alone.

In a nutshell, way back in 1189, just as the Kamakura era was kicking off, Minamoto-no-Yoritomo gave Chiba Tsunehide a solid pat on the back for his war efforts and handed him a chunk of land. The fief sat out in Shimotsuke, what we now call Tochigi, and included the areas of Nitobe, Takaoka, and Aoya. Tsunehide packed up the family and headed for Nitobe, where they settled in. Skip ahead five generations and Chiba Sadatsuna clearly fancied a bit of rebranding. Out went the old surname, in came Nitobe. From there, the Nitobe family story really began to write itself.

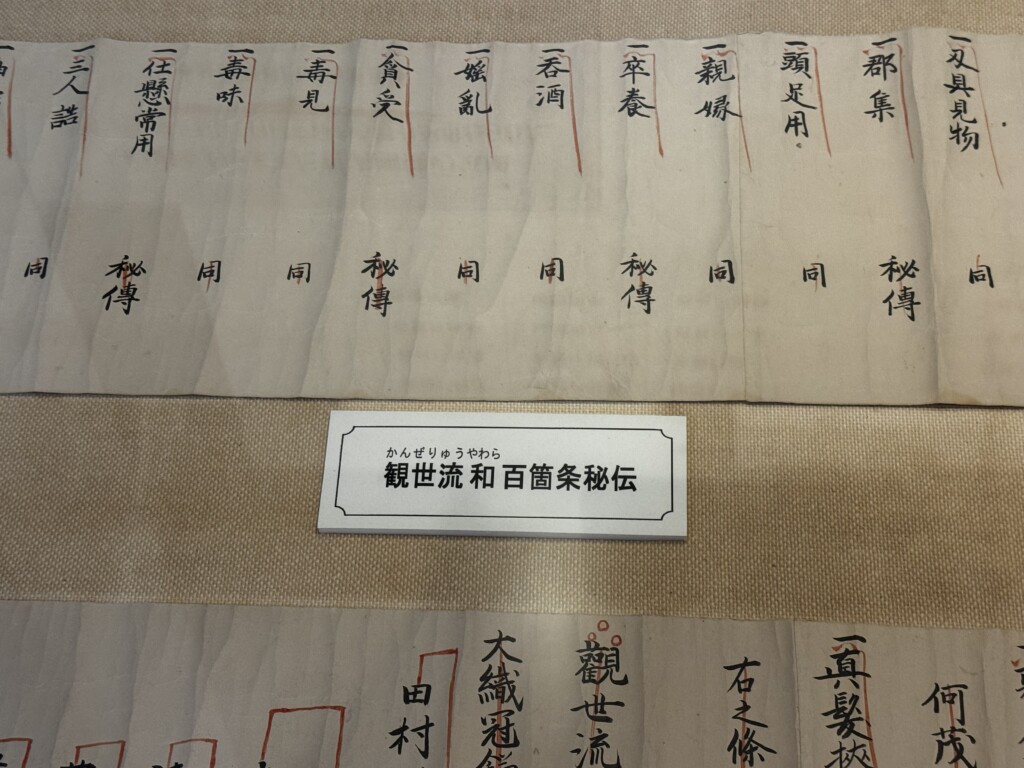

The museum in Hanamaki is a place where you can learn about the Nitobe past through records of their achievements, as well as exhibits tracing Inazō’s upbringing and life, using documents and actual artefacts. You walk through displays of genealogy charts, household objects, canal maps, and photographs, and suddenly Nitobe is no longer just an influential Quaker in Geneva who wrote a quaint little book about bushido, but the real deal heir of a samurai line that had lived in and around Hanamaki since 1598. For over two centuries, the Nitobe clan served under the Nanbu lords, instructing the castle retainers in both letters and martial arts while later on pouring their energy into land development. They were samurai who taught, fought, and dug with equal passion.

That context makes Nitobe Inazō’s famous words, “I wish to become a bridge across the Pacific”, sound less like lofty rhetoric and more like family inheritance. The Nitobe clan (not just Inazō) are still revered by people in the district to this day for what they achieved. They literally reshaped the landscape around them. When Inazō said he wanted to be a bridge, he was following in the family trade of connecting, cultivating, and building. This is very apt as Inazō’s illustrious international career in the post-samurai age remained very much centred on agricultural pursuits.

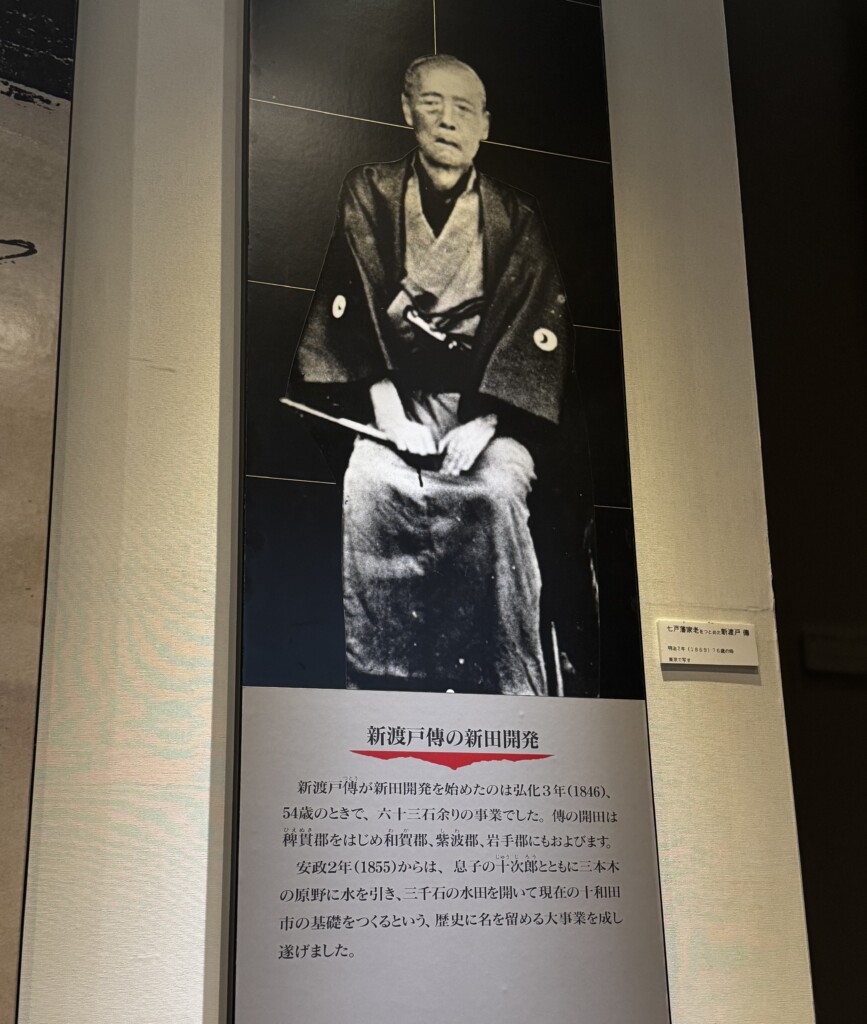

The exhibits begin with the practical side of samurai life in the north. Edo-period Morioka was hit by no fewer than seventy-six crop failures. Rice meant survival, and the Nitobe clan were instrumental in planning and constructing canals from Lake Towada to Sanbongi, transforming land that would otherwise have gone barren. One display shows maps of the Inaoi River project, completed around 1860 by his grandfather Tsutō and father Jūjirō, which guaranteed bumper harvests the following year. Then they laid out plans for a brand-new town called Inaoi-chō, laid out in a tidy four-way grid with a dozen neat neighbourhoods. That little project ended up being a blueprint for modern city planning in Japan.

Inazō (childhood name Inanosuke) was born around this time in 1862. His very name, Inazō, meaning “to produce rice”, was a tribute to that agricultural success. Seeing the irrigation plans alongside family records, you understand that service for the Nitobes was measured in full bellies, not battlefield triumphs.

Another display presents a set of swords that were heirlooms of the Nitobe clan. Looking at that, I was reminded of the coming-of-age ceremony when five-year-old boys of warrior families first put on the pleated trousers (hakama) and joined the samurai community. Apparently, Inazō stood on a go board, sword at his hip, and inducted into a centuries-old order. Within a decade, it was gone. The Meiji Restoration (1868) swept away the class system, outlawed swords, and left the samurai with nothing but memories (and normal haricuts). Later in life, he confessed that losing the sword made him feel “lonely in the loins”. People laugh at the phrase, but looking at those swords, I sensed the dislocation: a boy raised for one world, but pushed into another before he had knew what was going on.

The museum does not hide the darker parts of the Nitobe story, but doesn’t go into too much detail either. His father, Jūjirō, was accused of illicit trading with the French, selling silk without permission to raise money for development projects. He was put under house arrest. The charges were dropped, but the humiliation remained, and he died at age forty-eight “of despair”. It’s only alluded to in the museum, but if you know about it, you feel the sting. Nitobe’s later insistence that the worth of any act “lies in its motive and sincerity” was not just empty theory. It was personal testimony from a family that had seen hard-earned honour unravel overnight, but was ultimately salvaged through continued hard work.

There are lighter sides to the story, too. Inazō was a known shite as a lad, prone to fights, his mother forever apologising to neighbours. Once pushed toward study, he became relentless. The museum tracks his path to Tokyo, his adoption by his uncle Ōta Tokitoshi, his studies at the English school in Tsukiji, then Sapporo Agricultural College. The displays emphasise how foreign learning and Christian ideas gradually mixed with the traditional values drilled into him by his mother. When he signed the Covenant of Believers in Jesus at Sapporo and was baptised as Paul Nitobe, it was not a rupture so much as another graft onto an already complex inheritance.

Being able to read between the lines through my previous research into the man, the museum panels were clear to me: this was a clan that had always mixed martial obligation with practical service. Inazō simply carried that blend into new soil, so to speak.

Seeing all this made me reflect on my own work with Nitobe. A few years ago, I published an annotated edition of his Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan with Tuttle. I laid his rather convoluted text out with context, footnotes, and critical commentary. That book picked up an Independent Publisher Book Award, which was somewhat gratifying (thank you Inazō), but what mattered more was the process of really sitting inside Nitobe’s words. At an earlier time in my academic career, I treated his Bushido as a problem text, beautiful prose but somewhat unreliable history; an “invented tradition” packaged for a Western audience.

After walking through the Hanamaki museum, I was reminded again that this is not the fairest way to read it. If the nebulous ideas collectively known as bushido had always been a series of re-inventions, different voices shaping warrior values for their own eras, ranks, and regions, then Nitobe’s thesis is as legitimate as any. Seeing how far back his family stretches into samurai lore, how they lived duty in mud and maps, makes his ideals as valid as the strictures of Yamaga or Daidōji. He may have dressed it in pretty Victorian English, but the bones were his own.

The museum does not shy away from the later contradictions either. His role in colonial administration in Taiwan and as a professor in colonial policy at Kyoto University, his attempts to humanise Japan’s expansion, his awkward position in the 1930s, torn between loyalty to his country and loyalty to international ideals, all of it is presented plainly.

Popular polymath though he was, the notorious “Matsumoto incident”, when an offhand remark about militarists and communists got printed and he was forced to apologise before angry veterans, is not recounted (at least, I couldn’t see anything related to it). But in the photos of his later life standing proud with his American wife, Mary Elkinton, I could detect burgeoning signs of frustration in his eyes. Not because of his wife I should add! But because he traversed a time of absolute turmoil, domestic and international, and much of his later years were spent stuck between the proverbial rock and a hard place. Defending Japan to the world on the one hand, and criticising Japan to his countrymen on the other.

By the time you reach the final cartoon cutouts just outside the exit, the arc is complete. Born in Morioka in 1862 as the son of a samurai, Nitobe Inazō came of age just as the sword was about to be outlawed. Topknots cut away, the proud Nanbu samurai were reclassified as ordinary blokes. He became a Christian, a Quaker, and a fluent writer in English, and was perhaps the only man of his generation who could have written Bushido: The Soul of Japan, an expose on the Japanese people in a form the West was eager to read. It was polished, persuasive, guaranteed to annoy academics, and remains a bestseller to this day. Which is probably why it annoys academics!

From a boy in hakama standing on a go board to the “Star of Geneva” at the League of Nations, his life veered through loss, reinvention, and triumph before ending with the bleak irony of dying abroad in 1933 just as Japan turned its back on the internationalism he had spent a lifetime preaching. His was a life that never fits into a neat formula, but it makes sense if you see it as an extension of that family tradition in Hanamaki: service, adaptation, and the conviction that honour lives in motive.

Walking out with Jonathan, I mused that the museum hadn’t shifted my own reading of Nitobe. It had actually reaffirmed my understanding. With regards to his book on bushido, many experts will go on calling it flawed. Fair enough. But in Hanamaki you see the pedigree that gave it weight. The Nitobes had lived and worked as samurai for centuries. They had taught, fought, engineered, and survived. Nitobe was simply putting their values into print, in the only idiom that could make sense to his audience. It is quite brilliant, I think, when appreciated in this light.

No comments yet.