Budo Beat 38: The Philosophy of Zanshin No. 4 – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 3)

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The following is a translation of No. 4 of my 25-article series titled “The Philosophy of Zanshin” (残心の哲学) published in Japanese in the Nippon Budokan’s monthly magazine, Gekkan Budo (“Budo Monthly”, April 2023, pp. 30-35). It’s a rough translation, but I hope it offers some insight. You can read the previous articles at the following links:

No 1. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The Essence of Budo”

No 2. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin (Part 1)”

No. 3. The Philosophy of Zanshin – “The History of Zanshin” (Part 2)

Introduction

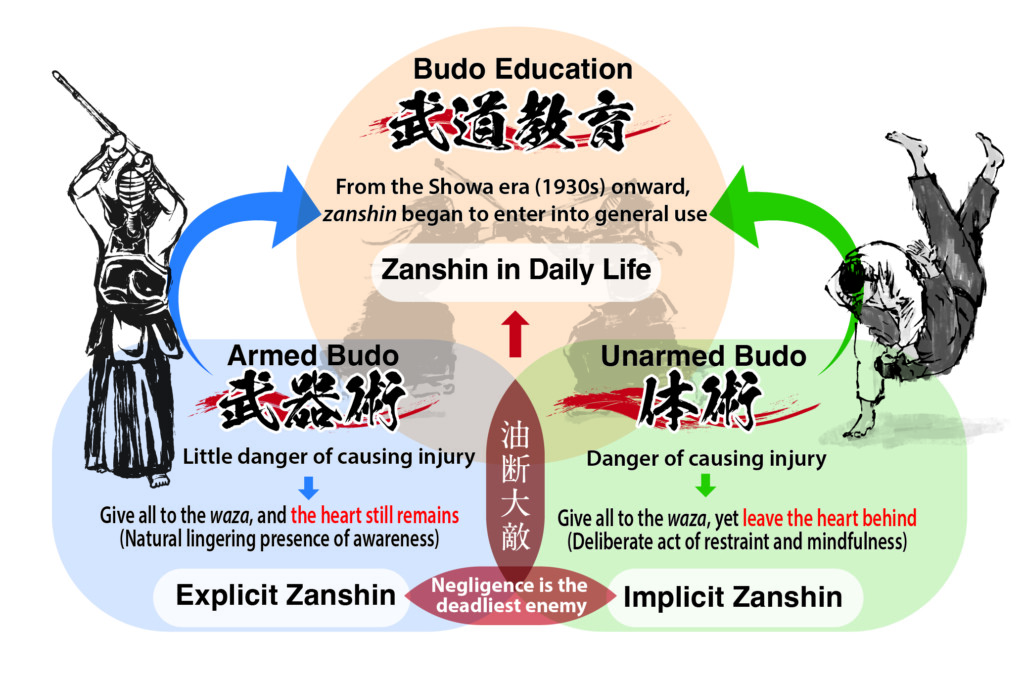

Last time, I focused on how the idea of zanshin has evolved within the context of kendo. This time, I want to consider how other budo arts have approached and incorporated the concept. During the Edo period (1600-1868), apart from a handful of schools of archery and jūjutsu, zanshin was rarely discussed outside of swordsmanship. That said, even when the word itself wasn’t used, the underlying mindset (what we might call “implicit zanshin”) was always present as a foundation in every martial art. It was only from the early Shōwa era (1926-1989) onwards that zanshin began to be widely accepted as a universal principle of budo. From that point, it developed beyond being a purely technical element at the “micro level” and grew into a broader, “macro-level” philosophical concept that could be integrated into everyday life as an integral part of the “Way” of budo.

Zanshin(残心)& Zanshin(残身)in Kyudo

When people hear the word zanshin, many immediately think of kyudo (Japanese archery). In kyudo, zanshin written with the kanji 残心 (= lingering mind) refers primarily to the mental state of remaining composed and not releasing tension after the arrow has been loosed. Whereas, zanshin written as 残身 (= lingering body)[1] refers to maintaining proper posture after the shot. One occasionally also finds the expression zanshin (残芯 = lingering core), which emphasises holding firmly to one’s inner centre or core until the very end. Today, both 残心 and 残身 are used, covering both the mental and physical dimensions of the concept.

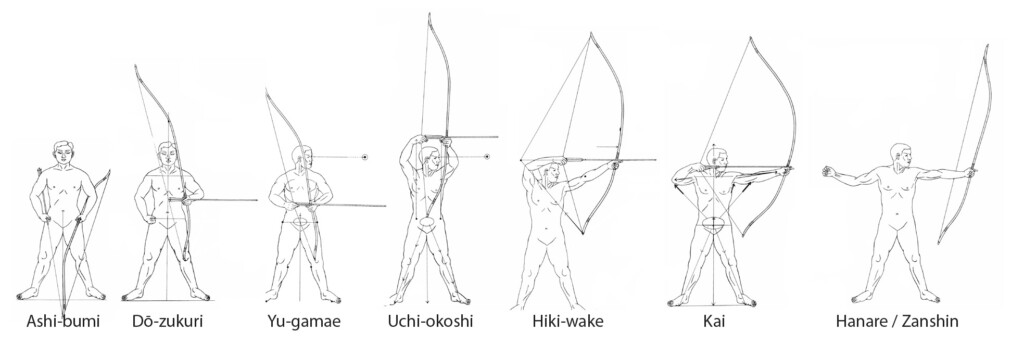

Zanshin is the final stage of shahō hassetsu (射法八節) — the eight fundamental stages of shooting that form the framework and standard of kyudo. These stages, with zanshin as their culmination, are as follows (as described by the All Nippon Kyudo Federation):

- Ashi-bumi (足踏み) – Open the feet and establish correct posture.

- Dō-zukuri (胴造り) – Place the bow against the left knee, the right hand at the right hip.

- Yu-gamae (弓構え) – Hook the right hand onto the string, prepare the left hand (te-no-uchi), then fix the gaze on the target.

- Uchi-okoshi (打起こし) – From yu-gamae, calmly raise both fists to the same height.

- Hiki-wake (引分け) – Draw the bow apart evenly to left and right.

- Kai (会) – With the draw complete, body and spirit unified, wait for the right moment for release.

- Hanare (離れ) – Open the chest fully and release the arrow.

- Zanshin / Zanshin (残心・残身) – The completion of the entire shot. Maintain the posture and spirit for a time after the arrow has left the bow.

It is not the release of the arrow that marks the end of the shot. The sequence is only complete with [both types of] zanshin. Even after the arrow has struck the target, the archer must maintain posture without breaking form, continuing to project ki (energy or intent). Furthermore, when leaving the shooting position, the action known as yudaoshi (returning to the posture of holding the bow at rest) is not treated as a separate step within the shahō hassetsu, but is considered part of zanshin. This signifies the true completion of the basic shooting procedure, while also establishing the transition to the next shooting position.

However, just as in kendo, the way of thinking and interpreting zanshin in the world of archery has shifted somewhat over time. According to Irie Kōhei (Emeritus Professor of Tsukuba University), in the case of zanshin within the Heki-ryū Dōsetsu-ha tradition of archery, five types can be identified: ① zanshin of the bow hand (oshite); ② zanshin of the string hand (katte); ③ zanshin of the eyes; ④ zanshin of the lower abdomen; ⑤ and zanshin of the heart. He further explains that there are two aspects to it: “the state of body and mind at the moment of uchiokoshi (the initial raising of the bow)” and “the state of body and mind after the release.” In other words, it was never limited merely to the final stage of shahō shooting process.[2]

Within the Chikurin-ha branch of the same Heki-ryū tradition, shooting is divided into “seven stages” (shichidō), with the seventh being the release (hanare), and zanshin (残身) is described as the physical state that comes afterwards. There is a particularly striking passage in Yashiro Jōzō’s Chikurin Shahō Taii (1922) under the section “Explanation of the Seven Stages”:

“If we were to compare archery to a human life: from ashibumi (foot placement) and dōzukuri (forming the body) through to hiki-tori (drawing) is the past; kai (full draw) is the present; hanare (release) is the end of life; and zanshin is the future—life after death. Human attachments resemble kai (meeting or come together) and hanare (parting or separation); therefore, it is said that those who ‘meet’ must inevitably ‘part’ (aesha jōri),[3] which is precisely why these stages are called kai and hanare.” (p. 41)

Furthermore, zanshin (残身) is explained as follows:

“Ato no nobi means the posture after the release (hanare). It is also called zanshin, or sometimes mikomi (continuation). In detail, it refers to the state of mind, body, and power after the arrow has left the bow. In other words, after completing the gobu no tsume (the five-part process) and releasing, in ato no nobi one’s posture must remain unmoving, the strength held firm, appearing dignified. On the contrary, if the release causes the tension of spirit to collapse into emptiness, or if one lacks sufficient reserve of strength, then seeking ato no nobi is impossible: the posture will break down and become most unseemly.” (p. 49)

The author notes that when an archer continues to maintain awareness of both body and mind even after releasing the arrow, the quality of the shot is elevated. It’s grace, beauty, and force are enhanced, and the presence or absence of zanshin makes the archer’s dignity and bearing immediately apparent to any observer. In other words, zanshin is what completes the shooting process, and it can be said to be a defining element of the philosophy of shin-zen-bi (truth, goodness, beauty), which is regarded today as the very essence of modern kyudo.

In Takeuchi Mamoru’s Kyūdō (1928), an instructional manual from the early Shōwa period, zanshin is described as follows:

“It refers to discerning the point where the arrow lands. For example, it is like when a boat approaches the shore: the oarsmen stop rowing four or five ken (7-9 metres) before reaching land, and simply wait for the boat to draw in. At that moment, a degree of reserve strength still remains, and one must hold a feeling of extension, as if able to continue further to the left and right. Then, once the landing point of the arrow has been ascertained, the upper hazu (tip of the bow) is tilted forward.” (p. 33)

It is thus clear that zanshin is an indispensable element in facilitating the refinement and gravitas expected in kyudo. However, until 1934 when the Dai Nippon Butokukai[4] issued the Kyūdō Yōsoku (Essential Regulations of Kyūdō) and introduced the standardised seidō forms, zanshin (残身) had not been included as a formal stage within the shooting method. At the time, there were critics of the Butokukai’s newly created “Kyūdō Kata” and Yōsoku, yet Tanaka Tomizō’s Shōwa Kyūdō (1936) quotes approvingly from the Kyūdō Yōsoku, praising the addition of the new “eighth stage”. According to his explanation:

“After releasing the arrow, without changing posture, fix one’s gaze on where the arrow lands. Zanshin refers to those few seconds in which the lingering resonance of energy (kiai) remains, without slackening. In order to create a fine zanshin from the very beginning, one must carry out the shooting with wholehearted effort. The quality of a shot can be judged instantly by a single glance at the zanshin. It is of utmost importance. That the Butokukai added zanshin as the eighth stage to the Yōsoku was, I believe, entirely appropriate.” (p. 69)

In modern kyudo of the postwar era, the All Japan Kyudo Federation stipulates that “zanshin of the body and mind is the final summation of the shot.”

Zanshin in Taijutsu[5]

What, then, of judo, which had such a profound influence on the modernisation and development of budo? As one of Kanō Jigorō’s many famous sayings goes:

“Win, yet never become arrogant in victory; lose, yet never be crushed by defeat. In times of ease, never grow complacent; in times of danger, never be afraid. Simply, simply, keep treading the one true path.”

This expression encapsulates perfectly both the micro and macro dimensions of zanshin. Yet, it is worth noting that Kanō himself, as far as I can ascertain, never actually used the word zanshin directly.

In the Kōdōkan journal Jūdō (Vol. 4, October issue, 1918), within the article “On the Forms of Kime no Kata”, however, we find the following explanation: “With the end of a technique, the spirit must not be cut off; what is called zanshin must always be present.” (p. 16). From what I can determine, this is the first appearance of the term zanshin in judo literature.

Another instance appears much later in Hoshizaki Osamu’s notable work Shin Jūdō Tachi-waza Hen (1933). Discussing the “essence” of Kōdōkan judo, he writes: “If there are techniques founded on mushin, then there are also techniques whose essence lies in zanshin. A practitioner should not choose one over the other. If a technique that requires mushin is performed with the attitude of zanshin, it is only natural that strain and collapse will easily appear as a result.” (p. 76)

In other words, there are techniques executed with the spirit of mushin (initiating an attack oneself), and there are techniques of zanshin (responding to the opponent’s attack). However, it is pointed out that one must not make a distinction and choose only one or the other. This is because forcing such a separation leads to failure of the technique. Namely, whatever the technique, one must put aside extraneous thought and throw one’s whole body and spirit into it. The explanation is admittedly rather difficult to parse, but it does reveal that by the early Shōwa period zanshin was being consciously explored as a technical and philosophical element within judo.

Even after the war, references to zanshin remain scarce in judo instructional texts. When it does appear, it is usually limited to concise definitions such as: “The attitude and mental readiness to prepare for a counterattack after throwing the opponent.” (Kōdōkan Waei Taishō Jūdō Yōgo Shōjiten, 2000, p. 27). Unlike in kendo, naginata, or jukendo, however, zanshin is not included among the official requirements to score an ippon under judo’s match regulations.

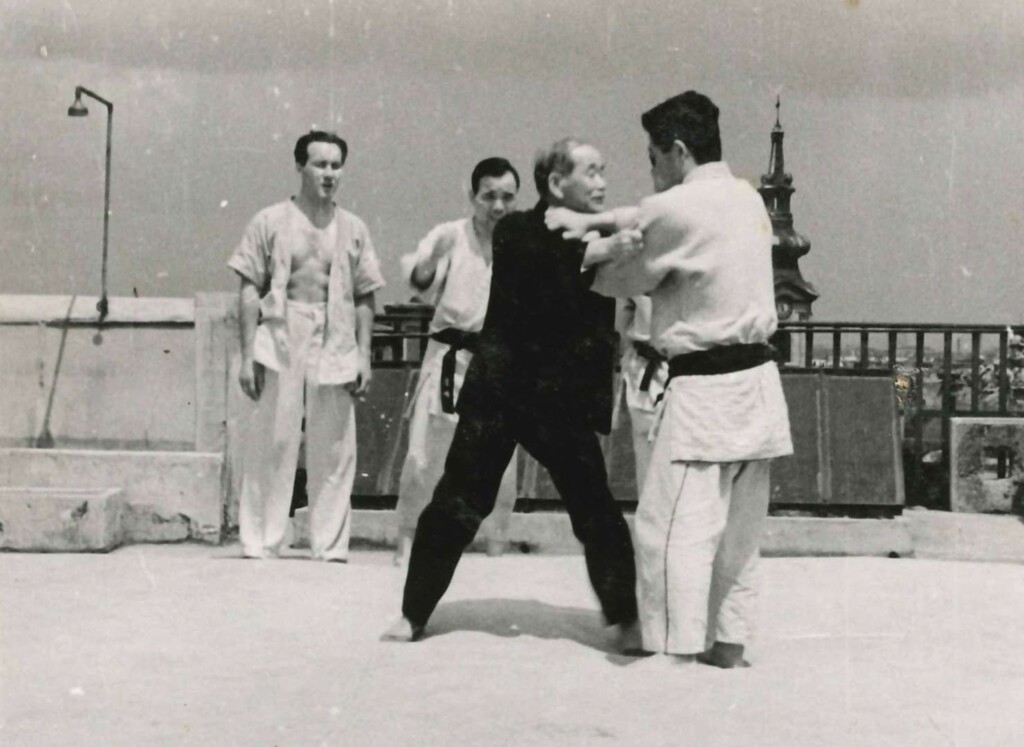

I once asked the late Murata Naoki (former Head of the Kōdōkan Library and Archives, and former President of the Nippon Budo Gakkai) about this matter. What he shared with me was a tale of Kanō Jigorō’s prowess. Between 1889 and 1890, Kanō was sent to Europe to observe educational institutions. On the ship returning to Japan, the Hikawa-maru, a Russian seaman aboard began boasting of his own strength after a few tussles with other passengers. Watching this, Kanō said words to the effect, “I reckon I could pin you down, and you won’t be able to get back up.” When challenged to back his words up, he held the large man down, and sure enough, the seaman was unable to rise.

When the man challenged him again, insisting on a “proper standing contest”, Kanō managed to throw him decisively. Yet as the Russian went tumbling headfirst, Kanō caught him with both hands to prevent injury. The passengers who witnessed the scene saw the principle of “jū yoku gō wo seisu” (softness overcoming strength) in action. They were equally struck by Kanō’s composure and compassion to prevent the giant Russian smashing headfirst into the hard deck, and the onlookers apparently erupted in thunderous applause.

Murata explained to me that the concept of zanshin in judo is not only about avoiding carelessness after executing a technique, but also about ensuring the opponent’s safety. Unlike weapons-based martial arts that rely on protective armour, judo techniques have the potential to cause serious harm. Thus, the timing of releasing a hold or the force applied in a throw must be governed not by a desire to damage, but by an attitude of “preserving life”. “Indeed,” Murata said, “it would not be an exaggeration to say that zanshin in judo lies precisely in the fusion of sappō (methods of killing) and kappō (methods of reviving and preserving).”

In sumo, the term zanshin appears in Masuoka Satoshi’s Sumō Kōhon (1935). In the section on preparatory exercises, he notes: “When returning to the original position after rising, the attacker must always move centripetally, and moreover this posture demonstrates zanshin.” (p. 155)

Likewise, in Karatedō Shūsei, Vol. 1 (1936), compiled by the Keio University Karate Club, we find what is likely the earliest appearance of the term in karate literature: “Both opponents, facing one another at the end of kumite, maintain zanshin, each seeking to discern an opening in the other.” (p. 130)

These examples emphasise the need never to let one’s guard down. Yet, as in the judo story, they also point to a mindset concerned with preventing injury to one’s training partner. In other words, what might be called an “implicit zanshin” was already present. Even in the writings of figures such as Ueshiba Morihei, the founder of aikido, or So Doshin, founder of Shorinji Kempo, the term zanshin itself does not appear. Nevertheless, the same posture of readiness and mental attitude—this implicit zanshin—is unmistakably there.

Karate-do also has other interesting ways of thinking about zanshin. Nakayama Masatoshi, founder of the Japan Karate Association, stressed during the postwar development of karate competition (kumite) that sun-dome refers to stopping a punch or strike just before it makes contact for safety reasons. However, it is not simply pulling the blow. The strike is aimed and delivered with the full intention of going through the opponent, only checked at the very last moment. Nakayama called this kime, which means the decisive focus and concentration of power at the end of a technique. He argued that if kime is lost, then zanshin, regarded as one of the essential elements of budo, also disappears. As Ohmori Toshinori explains in What is Osu? (2016), the Japan Karate Association placed great importance on this concept of kime, treating it as central to the very essence of “karate as budo”. (Ōmori Toshinori, Osu to wa Nanika? 2016. My English translation of this book is available here.)

Zanshin in Everyday Life

By the 1930s, under the wartime regime, budo came to be given considerably more emphasis within the school system, eventually becoming a compulsory subject. What was significant about budo education in schools was that, alongside technical training, moral elements were also taught. Thus, in budo textbooks, sections were included not only on building a strong and healthy body, but also on showing how the spirit of budo was closely tied to the moral character of the Japanese people. Instruction was given on how the teachings of budo could be applied and lived out in everyday life.

In this way, zanshin began to be highlighted not merely as a post-technique action for continued vigilance (micro), but for the first time in a broader, macro sense. The elevation of zanshin beyond the dojo is strikingly evident in Sonobe Shigehachi’s naginata textbook Kokumin Gakkō Naginata Seigi (1941). In his practical explanation he writes: “Even after striking with full force, the opponent may rise again, or a second or third adversary may appear. It is the mental state of readiness that enables one to respond fully to such possibilities.” (p. 290)

This mirrors the understanding of zanshin in kendo. What is particularly intriguing, however, is the reference to the “three principles of life”:

- A life of sincerity (shinken naru seikatsu)

- A life of initiative (sen no seikatsu)

- A life of awareness and follow-through (zanshin no seikatsu)

“Zanshin means carrying something through to completion. It also means taking proper care of what follows. There are two meanings here. One is that after striking the opponent with a single cut, one keeps the mind fixed on observing the opponent’s movement. In the moment of striking, however, the mind must never be left behind. One must put the whole spirit into it and strike with full power. When this is done, a residual awareness naturally remains and arises anew. It is like an autumn leaf falling from a tree, in which the new bud is already contained, and that bud has even greater vitality than before. In our own lives as well, if we simply rush from one thing to another and leave matters unfinished, we fail often. Unless we always leave our awareness behind and take care with what follows, things will not succeed. At the same time, unless we work with all our strength and to the very limits of our ability, our own powers will not develop. Therefore, we must always, under careful attention, give our utmost effort without holding back the mind, and furthermore see to the proper conclusion of things so that they are carried through to completion.” (p. 296)

In Nawata Tadao’s Kendō no Riron to Jissai (1938), under the section “Making the Virtues of Training Part of Daily Life,” we find the following passage:

“In kendo, for example, zanshin is constantly emphasised, but this should not be confined solely to kendo itself. Rather, by carrying zanshin into everyday life, we can live without the slightest gap or lapse. To make all the virtues acquired through training part of daily conduct is what gives kendo its true value.” (p. 56)

In short, the zanshin learned through budo is understood as a state of tightening and focusing both mind and body, and it is recognised as a concept that is also useful in daily life. It encourages attentiveness to one’s surroundings and care in one’s own actions, and is proposed as something that can be applied in many areas of life, from human relationships to work. By being aware of how one’s words and deeds affect others, one becomes more perceptive, and is able to cultivate better judgment directed toward long-term goals. This, it is argued, is the aim of budo education, and at the foundation of this ideal lies zanshin as a new, macro-level and philosophical way of thinking.

Summary

As introduced in Part 2 of this series, there are references to zanshin in the writings of Tenjin Shinyō-ryū jūjutsu, but such cases are rare among taijutsu-based martial arts. Even in the modern era, the concept of zanshin appears only infrequently outside of kendo and kyudo. Of course, as culture born from the battlefield, these arts naturally retained the principle of yudan taiteki—“Negligence is the deadliest enemy.” Yet, the specific term zanshin was seldom invoked.

The period when zanshin began to appear, albeit sparingly, in the writings of martial arts other than kendo and kyudo coincides with the 1930s, when budo was being enthusiastically promoted in schools. This era saw a rise in instructional manuals and the need for standardisation of budo concepts. It bears repeating: this does not mean the notion of zanshin did not exist before, but rather that as the various martial disciplines developed, they gradually began to adopt the term itself, most likely drawing first from kendo. Moreover, while there are common threads in how zanshin is interpreted across different arts, each discipline also has its own distinctive reading of the concept. This reveals the depth and richness of zanshin as a philosophy.

In the next instalment of this series of articles, I will examine whether concepts equivalent to zanshin can be found in foreign martial traditions.

[1] In early kyudo writings, the term 残身 (lit. “lingering body”) was used with the understanding that it referred not only to the residual stance of the body but also to mental composure, since body and mind were considered inseparable. In more recent kyudo texts both 残身 and 残心 (“lingering mind/spirit”) appear, the latter emphasising the psychological dimension more explicitly. In other budo traditions, however, 残心 is almost exclusively used, while 残身 remains rare outside of kyudo.

[2] Irie Kōhei, “On the Order and Historical Changes in the Terminology of Kyūdō Shooting Method Composition”, Budo Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1978, pp. 13–22.

[3] In Japanese today it’s sometimes shortened to 会者定離 (esha-jōri) and used in funeral inscriptions, temple writings, or even in literature to remind people to value encounters while they last, since parting is inevitable.

[4] The Dai-Nippon Butokukai (Greater Japan Martial Virtue Association) was founded in Kyoto in 1895 as a private organisation to preserve and promote the martial traditions of Japan, standardise instruction, and foster moral cultivation through budo. It played a central role in the development of modern kendo, judo, and other martial arts by organising national events, accrediting instructors, and publishing training manuals. Although initially independent, the Butokukai was brought under direct government control in the late 1930s, before being dissolved by the Allied Occupation authorities in 1946 as part of wider demilitarisation policies.

[5] Taijutsu refers to budo disciplines that don’t typically use weapons such as judo, karate, aikido etc.

No comments yet.