Budo Beat 31: When Martial Arts Meet Mirth

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

On my recent sojourn to Idaho for a Nito seminar, an opponent cheerily informed me that sparring with me had been “fun”. And that other people were “having fun” with me too! Was I being gently mocked, tactfully informed of incompetence, or merely categorised as a budo clown? Or, was it a compliment, implying that my presence on the dojo floor brought a certain “levity” or even a welcome unpredictability to the practice? Hmm…

This seemingly innocent remark sent me spiralling into an existential contemplation of “fun’s” place in the dojo. I must admit, despite the sometimes-terrifying intensity of training, I genuinely enjoy it. I’ve noticed myself smiling a lot these days, right in the thick of the fray. It relaxes me, and confuses the hell out my opponents wonderfully! But I should state from the outset, in no way am I taking the piss. Quite the opposite, in fact.

Hōzōin-ryū spear-fighting offers, among its inner secrets, a pearl of wisdom delightfully named “Daietsugen” (大悦眼 = the “Eyes of Great Joy”). Rather than the typical martial glare intended to vaporise opponents at ten paces, the spear fighter is counselled to flash a subtle smile through relaxed eyes. The effect is significant: relax the gaze with a cheesy grin, and the face and shoulders swiftly follow suit, coaxing the body naturally into easy readiness. Mind and limbs suddenly feel unshackled, fluid, ready for anything. Frankly, this little gem isn’t just for spear enthusiasts. It’s a charmingly sensible insight for all forms of budo and could even add a dash of sanity to the hurly-burly of modern life where a gently smiling eye might just be our best line of defence.

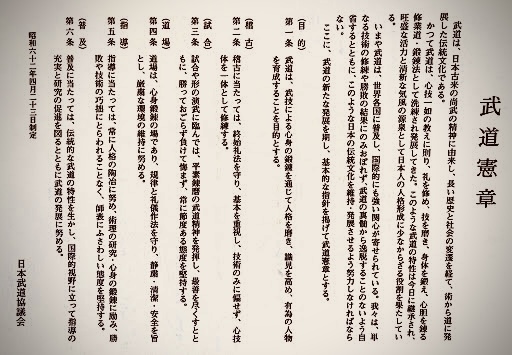

In any case, in the solemn sanctuaries of budo, tradition really hangs heavy in the air. This is a good thing for sure. The meticulously polished floor, neatly arranged gear, and quietly spoken greetings all conspire to cultivate an atmosphere thick with reverence, discipline, and serious intent. The “Budo Charter” expresses these ideals succinctly, stressing that the dojo is a place not merely of physical training but of mental and spiritual refinement.

“The dojo is a special place for training the mind and body. In the dojo, budo practitioners must maintain discipline, and show proper courtesies and respect. The dojo should be a quiet, clean, safe, and solemn environment.”

As an extension of this ideal, those there ultra-traditionalist “Protectors of the Way” insist with po-faced authority that the dojo is a sacred place where “life and death” hang precariously in the balance, asserting that anything less than “absolute solemnity” veers dangerously close to jadō (邪道)—a perversion of the true path. I.e., taking the piss. I remember one fellow on FB even lambasting me for a post-keiko group photo with participants taking some silly poses. “Shouldn’t behave like that in a dojo. It’s disrespectful!” he said.

I totally get it, but is it always really the case? Each dojo cultivates its own culture and training atmosphere, and over the years in Japan and abroad, I have observed that a good dose of levity and light-heartedness in the right places has an extraordinary power to “enhance and humanise” the budo experience.

So, what do I mean by “levity”? Levity refers to a sense of humour, mirth, light-heartedness, or cheerful lack of too much over-the-top urgency as seen in cults. It’s the quality of bringing breathable lightness to heavy topics or tense environments. And, this sense of ease helps practitioners step back from the blind intensity of training, providing clarity and perspective even in complex or challenging moments.

Looking back through the annals of budo history, levity has quietly served as a gentle ally to the greatest of masters. Miyamoto Musashi’s humour, for example, was certainly dry, subtle, and edged with irony rather than outright laughter or comic frivolity. His writing in the Gorin-no-sho never gives way to overt jokes, but it does exhibit flashes of sardonic wit and sly commentary about human foibles. Further evidence is found in Musashi’s calligraphy and ink paintings. Many of these reflect a playful approach to traditional themes: mischievous birds, quirky portraits of Daruma, and clever visual puns. This artistic playfulness suggests that beneath his severe warrior exterior, Musashi appreciated life’s ironies and absurdities.

Admittedly this is all conjecture! But, I have it on good authority from the late Professor Murata Naoki that Kano Jigoro, the esteemed founder of judo, was renowned not only for his technical expertise and gravitas, but also for a sense of humour that could effortlessly dissolve tension. Kano’s Kodokan dojo was a place of intellectual and physical rigour, but it was equally a space where laughter and friendly banter punctuated training sessions. His capacity to make a student chuckle at the absurdity of a mistake often led to a deeper, more relaxed understanding of judo’s principles.

Similarly, according to Kanazawa Hirokazu, Funakoshi Gichin, the father of Shotokan, maintained a gentle demeanour that ran counter to the stereotypical hard-arse severity associated with karate instructors. His famously soft-spoken nature and frequent gentle smiles were, in fact, vital elements in making his teachings accessible and relatable. Perhaps Funakoshi knew that joviality could unlock doors that rigid discipline alone could never open. His method of instruction, mixing seriousness with warm-hearted humanity, highlighted his understanding of budo as not only a martial discipline but as a path to human development.

I recall vividly my high school days spent deep in kendo practice in Japan. The dojo was horribly daunting. It was an austere place that demanded nothing short of total focus and obstinate fighting spirit. It could feel utterly stifling, especially for a young Kiwi exchange student like me. But paradoxically, my most enduring memories from those days aren’t of stringent bollockings or torturous drills, but rather the unexpected laughter that would occasionally burst forth from our stern-faced sensei or a mischievous senpai.

Once, during a gruelling training session (well, they all were actually), a fellow student was thrust unexpectedly backwards, limbs flailing and shinai flying, careening helplessly towards a cluster of 6 or 7 bystanders awaiting their turn. There was a momentary freeze-frame (I can still see it), their eyes widening in collective horror before the inevitable collision sent them sprawling like skittles in a ten-pin bowling alley. It was the perfect “Strike”! The dojo clamour stopped for an instant, until our sensei, normally the epitome of criminal-grade menace, broke into a fit of laughter. It was infectious, washing over all of us like a wave of relief, breaking down the fear and tension.

Critics might well argue that laughing or introducing a touch of humour risks trivialising budo’s dignity. Yet this viewpoint, I think, misunderstands the very nature of balance, a concept at the core of budo itself. I am of the belief that severity without levity leads to rigidity, while levity without seriousness results in frivolity. The essence of budo lies in achieving harmony between seemingly opposing forces.

In this sense, levity in budo isn’t about undermining respect or trivialising the discipline. Rather, it’s about sharing a laugh at our slip-ups or some other happening; it doesn’t need to diminish the seriousness of the training. It acknowledges our humanity, transforming the dojo from a grunty training ground into a gathering of kindred spirits, bonded by shared missteps and quiet triumphs.

Through my years of teaching and training around the world, I’ve come to realise that humour crosses cultural boundaries effortlessly. Whether I am at a seminar in Japan, Croatia, New Zealand, or elsewhere, a well-timed joke or anecdote breaks the ice and builds bridges. Students who feel comfortable enough to smile and laugh become more receptive, more curious, and ultimately more dedicated to their practice.

A bit of humour and levity, like an invisible thread woven through fine fabric, enriches the experience immensely by adding warmth to the necessarily disciplined atmosphere, harmonising interactions, and fostering the conditions necessary for genuine improvement and lasting connections. Ultimately, I reckon it fosters a deeper, internal kind of strength rooted in confidence, openness, and emotional resilience.

This broader view brings to mind a quote by G. K. Chesterton from his novel The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare (1908), which, I think, captures the point of this message:

“Moderate strength is shown in violence; supreme strength is shown in levity.”

Here, Chesterton contrasts two approaches to strength: violence represents a forceful, immediate display of power (moderate strength); whereas levity (lightness, humour, and grace) embodies a deeper, steadier supreme strength. Real power, therefore, might stem not from brute force but from poise, graceful wit, and calm, smiling self-assurance. Perhaps this, more than anything, encapsulates the spirit of budo. Reflecting on this, being remembered as ‘fun’ might indeed be good praise for a martial artist. What do you think?

No comments yet.