Budo Beat 21: Shu-perb, Ha-mazing, Ri-markable

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

First. Sorry about the title…

I’ve recently embarked on delivering an online course for Waseda University, attempting—bravely or perhaps foolishly—to somehow condense the profound essence of budo into digestible wisdom. The first concept on my intellectual chopping block was the venerable and endlessly fascinating notion of shu-ha-ri (守破離). I chose this deliberately, aiming to underscore the critical point that budo transcends mere technical accomplishment, unfolding instead as a lifelong, intricate dance of self-discovery, perpetual learning, and constant personal evolution. Indeed, it seemed only fitting to begin with a concept that encapsulates budo’s essence as an inexhaustible journey rather than a fixed destination.

My first encounter with shu-ha-ri was back in 1987 during the written portion of my kendo Shodan exam. At the time, it struck me as nothing more than some obscure, hocus-pocus concept—mystifying and distant. However, over the years, as I’ve grown and ‘matured’ in both budo and life, I’ve come to appreciate its significance and wisdom.

Now, if martial arts were merely physical, a sturdy punchbag would be the ultimate sage. But there is something more subtle at play—something ineffable, rooted in centuries of thoughtful refinement. Interwoven intricately with Japan’s vibrant tapestry of cultural arts, shu-ha-ri encapsulates the journey from earnest adherence to masterful transcendence. Its significance lies not merely in technical proficiency, but in the personal and spiritual growth it represents.

The essence of shu-ha-ri can best be distilled into a simple, poetic dictum drawn from Takano Sasaburō’s venerable text Kendō: “At first, train openly and boldly in the techniques. In the middle stage, explore widely. In the end, waste nothing.” Takano quotes this maxim from the Itto-ryū oral tradition, which neatly describes budo training as progressing from initial physical loosening, through rigorous exertion, and finally into spiritual refinement.

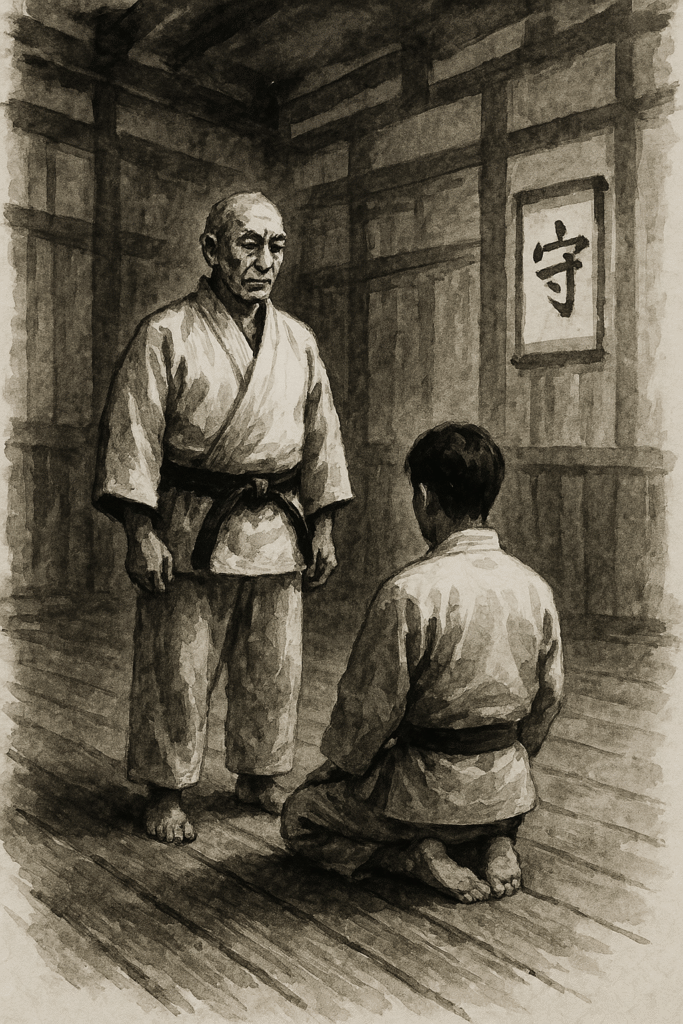

At the outset, we find shu (守), the stage of faithful imitation. Picture a fledgling swordsman diligently mirroring the master’s every move, absorbed in the earnest repetition of kihon—those fundamental techniques drilled into muscle memory. It is here, at the threshold of martial study, that foundations are established through expansive, unrestrained movements designed to liberate the body and mind from restrictive habits. This phase echoes the Buddhist concept of kai (戒 = śīla), embodying disciplined adherence to moral precepts—similarly fundamental yet indispensable. In essence, kai is not merely about following rules. It is a discipline of the heart, a commitment to living with awareness, responsibility, and compassion. It guards against chaos within, and harm without. Or put more simply: kai is the art of walking straight in a crooked world. This is shu.

Moving on to ha (破), or breaking away, the trainee—now adept in fundamental techniques—begins exploring and testing boundaries. This is where training becomes dynamic and investigative, a stage marked by intellectual curiosity and courageous experimentation. Martial artists in the ha phase venture boldly beyond their original teachings and out of their comfort zone, blending insight from varied sources and methods, enriching their practice through exposure to alternative styles and approaches. This corresponds to the Buddhist notion of jō (定 = samādhi), a meditative concentration emerging naturally through repeated, mindful practice. In short, jō is the deep, stabilising stillness of mind through which true insight arises—a still pool in which the moon of truth may be clearly reflected. Do what you are taught with purity of mind.

Then comes the final ascent to ri (離), transcendence. At this summit, a practitioner rises above both the discipline of imitation and the creative ferment of experimentation. It represents a state of true mastery where technique ceases to bind, instead serving as a seamless extension of intuition. Practitioners here move beyond form and convention, their actions dictated by an almost spiritual spontaneity—a vivid expression of mushin (no-mindedness). This resonates with the Buddhist concept e (慧 = prajñā), where the mind achieves clarity, effortlessly navigating complex realities without conscious deliberation. E is the clarity of awakened seeing, the ability to distinguish truth from delusion, reality from illusion. It is the final flowering of a disciplined life and a calm, concentrated mind. If kai is the compass, and jō is the still water, then e is the moon reflected perfectly upon its surface.

But shu-ha-ri, far from being confined solely to martial realms, extends roots deeply embedded in broader cultural and philosophical traditions of Japan. One striking parallel is found in the performative elegance of Noh theatre, particularly in the teachings of Zeami Motokiyo (1363–1443). Zeami’s concept of jo-ha-kyū (序破急). It is a concept of structured progression, often seen in music, theatre, and martial arts, where a movement or performance begins slowly and deliberately (jo), builds in complexity and intensity (ha), and culminates in a swift, decisive climax (kyū). It reflects a natural rhythm of unfolding and resolution, emphasising pacing, timing, and flow. Like shu-ha-ri, jo-ha-kyū embodies a deep understanding of progression—starting with form, breaking into dynamic expression, and arriving at a point of spontaneous mastery. Zeami stressed unwavering adeptness of basics as a platform for artistic innovation—capturing precisely the tension between adherence and creativity at shu-ha-ri’s core.

Further reflections emerge from the contemplative art of Chanoyu, the tea ceremony, greatly shaped by Sen-no-Rikyū (1522–1591) in the 16th century. Rikyū encapsulated this philosophy beautifully in his pedagogical verse: Adhere completely to the rules and forms—even if you break them, even if you transcend them, never forget their source.”[1] He counselled devotees to master rituals meticulously (shu), daringly innovate upon them (ha), yet always take with you their essential meaning (ri). This teaching significantly influenced the evolving discourse of shu-ha-ri, embedding within martial philosophy an enduring message of respect for tradition coupled with fearless creativity.

Shu-ha-ri gained explicit martial articulation only later, notably during the Edo period (1600–1868) through tea master Kawakami Fuhaku (1716-1807). While Fuhaku taught within the refined domain of tea ceremony, his elucidation closely paralleled martial disciplines. He wrote the following which is probably the first text to explicitly explain the concept of shu-ha-ri.

“Shu means to protect, ha means to break away, and ri means to separate from. Teaching the disciple corresponds to the stage called shu. When disciples have thoroughly mastered shu, they naturally progress toward ha by themselves. This is the stage of advanced skill. However, remaining only in shu is incomplete; likewise, staying only in ha is incomplete. It is only by transcending these two stages that one becomes a true master. Ri involves integrating and going beyond the previous two stages, yet it also means continuing to preserve their essential core.”[2]

He emphasised mastering orthodox practices under a single instructor (shu), courageously exploring variations and styles (ha), before finally emerging into personal, intuitive expression (ri). This triadic formulation, distilled from cultural wisdom accrued over centuries, now illuminates the path in martial arts, resonating intensely with practitioners of budo.

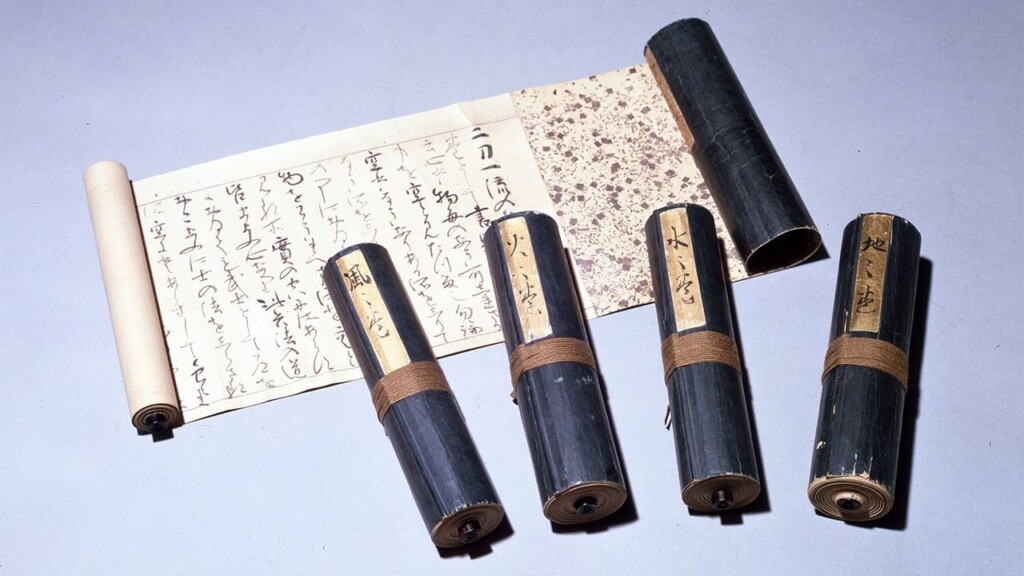

The relevance of shu-ha-ri to martial artists is also powerfully reinforced by seminal martial texts. Although he doesn’t use the term, Miyamoto Musashi’s Book of Five Rings echoes shu-ha-ri’s essence in the clear-eyed clarity of its counsel: progress step by patient step, respecting incremental mastery. Musashi asserts the necessity of continuous reflection, ever mindful of the ultimate goal—the warrior’s inner growth and transcendent understanding. Here again, the shu-ha-ri framework subtly guides practitioners toward a deeper comprehension of martial artistry not merely as physical prowess but as holistic human development.

In contemporary budo practice, shu-ha-ri remains essential. Beginners disciplined in technique gradually test their understanding, subsequently evolving towards uniquely expressive mastery. This developmental arc prevents stagnation, promoting continuous personal and technical growth. Those who grasp shu-ha-ri navigate martial arts as an enduring, enriching journey rather than mere mechanical repetition or shallow competitiveness.

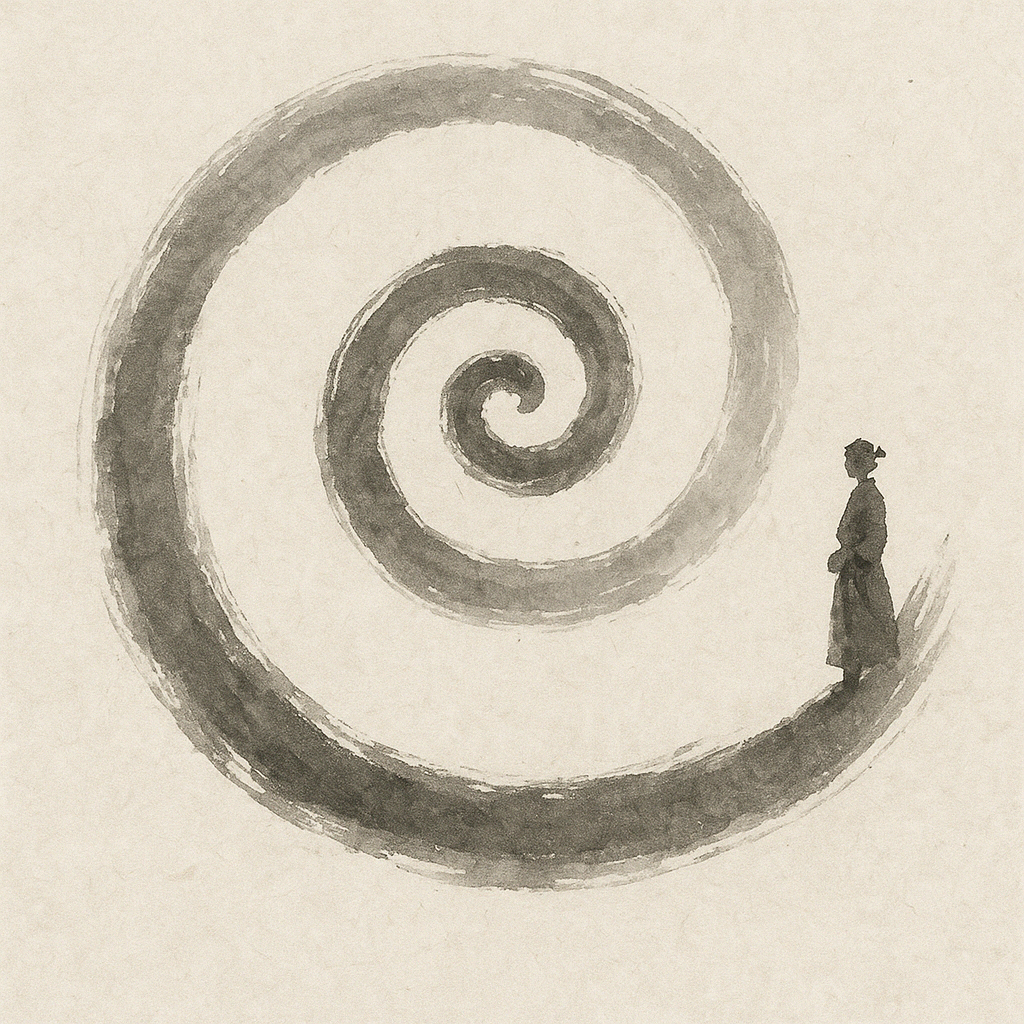

Importantly, shu-ha-ri, I believe, is not linear—it does not simply start and finish. Rather, it unfolds like an ascending spiral, perpetually cycling through shu, ha, and ri, each repetition at a higher level of refinement. The journey continues as long as one practices, forever deepening and evolving in skill, insight, and self-awareness.

All said and done, shu-ha-ri offers a pretty neat paradigm for understanding martial arts as an ongoing journey rather than a destination. From diligent mimicry (shu), through critical exploration (ha), to ultimate transcendence (ri), it mirrors universal human growth—embracing tradition yet advocating continuous innovation and authenticity. As Zeami, Rikyū, and Fuhaku illustrated vividly in their artistic disciplines, this balance between reverence and creative freedom defines genuine expertise.

Thus, shu-ha-ri endures—not as a final destination, but as a gentle reminder that the truest artistry lies not in conquering stages, but in savouring each spiralling ascent with wry curiosity and humble elegance. Embrace the perpetual ebbs and flows of shu-ha-ri! You’ll need it for your Shodan…

[1] 規矩作法 守りつくして 破るども 離るるとても本を忘るな (Kiku sahō mamori tsukushite, yaburu tomo, hanaruru tote mo moto o wasuru na). In Rikyū Hyakushu Shikai, authored by Kanazawa Sōi, published by Chadō Geppōsha, 1927, p. 129

[2] Fuhaku Hikki, edited by Edo Senke Chanoyu Kenkyūkai, published by Edo Senke Chanoyu Kenkyū-shitsu, December 1979. P. 164

No comments yet.