Budo Beat 20: Poise Under Pressure

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

Kigurai (気位)—there it stands, elusive yet alluring, another one of those maddening Japanese budo terms that deftly dodge neat English equivalents. It drifted persistently through the air at the recent “49th Foreign Kendo Leaders’ Seminar” (Kitamoto Seminar). As a translator, I gladly yield to its original charm and prefer simply to use the word kigurai itself. By now, I suspect enough people already understand the term and its significance. When I do render it into English, however, it goes something like “dignified presence” or “commanding presence”. I picture it as a flawlessly drawn bowstring—balanced tension, graceful precision, poised with latent power—qualities at the very soul of budo.

In Japanese culture, the kanji for kigurai literally combine the characters 気 (ki), meaning “spirit” or “energy”, and 位 (kurai/gurai), meaning “rank”, “status”, or “posture”. Together, they signify a “spiritual rank,” or more precisely, a refined and elevated state of dignity that naturally develops through education, continuous effort, and accumulated experience. It implies respecting oneself and taking pride in one’s own character and accomplishments. Yet, outside of budo, the phrase “someone with high kigurai” often carries negative connotations, associated with arrogance, excessive pride, or difficult personalities. In everyday contexts, it can imply self-centredness or narcissism, suggesting a person who is challenging to engage with socially.

However, in the realm of Japanese budo, kigurai embodies something entirely different. Far from self-centredness or vanity, it represents a deep and sincere quality cultivated over years of diligent training. Imagine a master musician stepping onto the stage before a packed concert hall; even before striking the first note, their poised silence fills the air, capturing everyone’s attention and signalling their artistry. It’s kind of like that.

Historically in budo, the term kigurai appears extensively from the Bakumatsu period (mid-1800s) onwards, reflecting widespread usage across various martial art schools of the era. Even within major martial traditions such as Hokushin Ittō-ryū, writings by disciples repeatedly referenced kigurai. Chiba Shūsaku famously taught, “To let your spirit be like a high-ranking court noble, while your technique should be like a humble servant”, or words to that effect. This instruction still resonates today in modern budo training, illustrating the ideal manifestation of kigurai.

Similarly, in budo, kigurai is vividly demonstrated at the precise moment of engagement—just before physical action begins. It is in this charged, silent instant, when two practitioners face each other, weapons drawn, that the true power of kigurai emerges. The practitioner who exudes genuine kigurai establishes psychological dominance through calmness, clarity, and inner authority, influencing the opponent’s state of mind even before the first strike is executed.

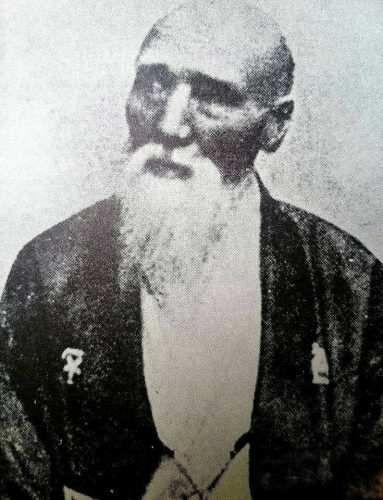

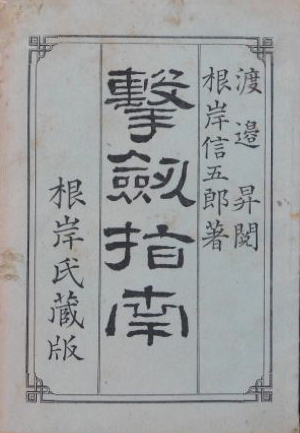

As described in the 19th-century text Gekken Shinan by Negishi Shingorō, “One must first master the previously outlined techniques, spirit (kiai), and distancing (maai), and only thereafter delve into the study of kigurai.” At this stage, the primary objective is to cultivate the inner fortitude of confronting a real blade. In this context, kigurai emerges naturally, a dignified aura marked by serene fulfilment and steadfast composure, arising effortlessly through persistent practice and sincere commitment to self-improvement.

Thus, having kigurai involves transcending mere physical techniques and cultivating an inner fortitude necessary when confronting a real blade. Kigurai, described in Gekken Shinan, “involves elevating and broadening one’s own mind to scrutinise the hidden intentions and schemes of the opponent.” The practitioner must intuitively sense the opponent’s intentions, as “recognising the opponent’s movements is neither about swiftness of vision nor rapid technique execution.” Instead, it requires “the soul’s direct perception”, discerning precisely where the enemy’s focus is lacking and exploiting vulnerabilities. (This connects nicely with the topic of my last blog post, → kizashi. Ah, the budo puzzle—each piece clicking gently into place, mostly by accident.)

Anyway, effective use of kigurai means enveloping and suppressing the opponent’s spirit, causing the adversary to become “breathless and constrained in movement.” How many times have you experienced this in the dojo? Going up against some old-timer, and somehow having the lifeforce mysteriously sucked out of you as you huff, and you puff yourself into oblivion 😰 …

Thus, Negishi tells us, victory emerges not from overtly aggressive actions but from subtly dominating the psychological battle: “when confusion emerges, the mind cannot adequately focus on all points, inevitably exposing weaknesses.” Mastery, he asserts, “culminates in the silent understanding or intuitive resonance known as ishin-denshin”, the rather nebulous principle of transmitting thoughts without words. Ultimately, this level of mastery cannot be explicitly taught but must be “accumulated through personal experience and understanding.”[1]

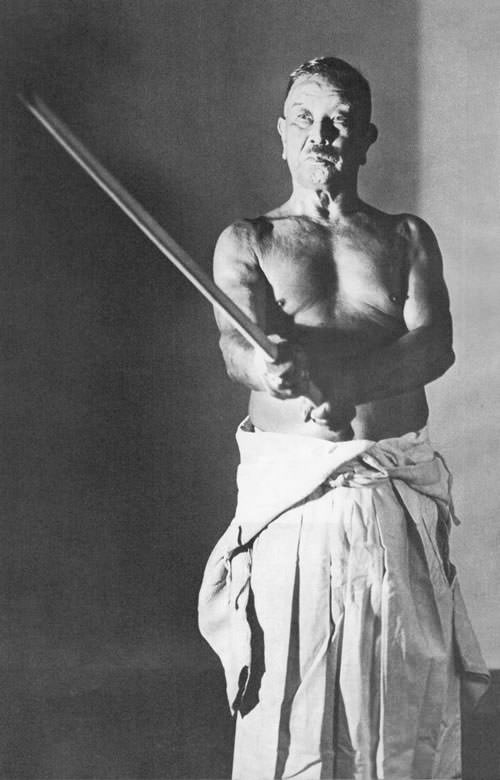

The widespread adoption and standardisation of the term kigurai in modern budo owe much to Takano Sasaburō, a prominent early kendo instructor. Takano frequently emphasised this concept in educational texts during a period when budo was incorporated into school curricula in the early decades of the 20th century, embedding the concept deeply into modern martial arts culture. Takano described kigurai in the following way.

“Kigurai, much like kiai, involves a subtle working of the spirit that is difficult to clearly express with brush or pen. In simple terms, one might describe kigurai as the power emanating naturally from self-confidence. It arises from a spirit of unwavering resolve, free from doubt or confusion, and thus carries with it an air of inherent dignity and authority. From this vantage point, one stands elevated above the opponent, looking down upon them, intuitively perceiving their spirit and technique, thereby instilling in them a sense of dread and hesitation, forcing them inevitably into shrinking back.”[2]

He went on to describe it as akin to observing an enemy from atop a high mountain—where all hills, ridges, rivers, and valleys below seem clearly within immediate reach. With a calm and commanding spirit, the opponent’s every movement becomes vividly apparent, and controlling, defeating, striking, or thrusting at them becomes effortlessly achievable.

Conversely, from the enemy’s perspective, engaging an opponent endowed with true kigurai feels like peering into a bottomless abyss or attempting to scale an insurmountably high mountain. “Fear and confusion take hold, their movements become hesitant and constrained, mental clarity dulls, breathing grows strained, and ultimately, they succumb, unable to sustain their courage.” We’ve all been there!

The resonance of kigurai, however, extends beyond the martial arts dojo and into broader human experience, finding compelling parallels in Western literature and historical figures. Ernest Hemingway succinctly captured its essence as “grace under pressure”, an elegant phrase highlighting poised dignity amidst adversity. Marcus Aurelius similarly evoked this steady, dignified resilience by advising, “Be like the cliff against which waves continually break; but it stands firm and tames the fury of the water around it.”

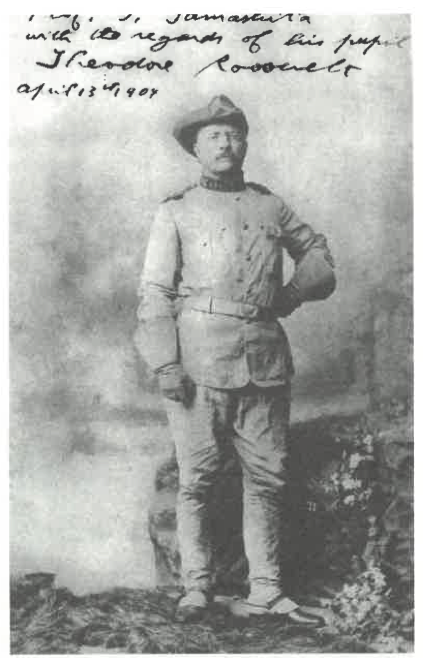

I recently came across 26th US President Theodore Roosevelt’s famous dictum, “Speak softly and carry a big [kendo😬] stick; you will go far.” I think that this, in an interesting kind of way, conveys the quiet yet commanding authority intrinsic to genuine kigurai, where strength lies not in overt aggression but in composed, unwavering confidence. Apparently, Roosevelt’s approach to what is known as “big stick diplomacy” rested upon five fundamental principles, all delivered with the bracing clarity one might expect from Teddy himself.

First, he insisted on genuine military strength—so impressive it would make potential adversaries sit up and reconsider their plans. He also counselled dealing with other nations justly, never bluffing (bluffers inevitably trip themselves up), and ensuring that when striking became necessary, it was done swiftly and decisively. Perhaps most cleverly of all, Roosevelt urged allowing the defeated adversary to depart with dignity intact—a touch of grace preventing needless humiliation. Together, these qualities capture precisely that blend of authority and subtlety central to the notion of kigurai in budo.

In sports psychology, we’re constantly told to “fake it until you make it”—a neat mindset for gaining confidence or projecting positivity. But genuine kigurai resists such easy imitations. Attempts to fake kigurai inevitably fall flat, exposing the pretender not as dignified, but as obnoxiously arrogant, strutting about like a “samurai fairy” with their head firmly lodged somewhere unmentionable. True kigurai emerges naturally, quietly asserting itself only after one’s technical skill has matured, and the spirit has been thoroughly tempered.

Thus, kigurai is far more than a lofty abstraction or poetic flourish—in some ways it’s the tangible yet mysterious centre of budo, an unspoken dialogue between spirit and technique. Rather than offering easy answers or quick victories, it demands relentless attention, quiet reflection, and a lifetime of sincere, persistent practice. Ultimately, through cultivating kigurai, martial artists come to understand not merely how to command a bout, but how to embody the subtle power and poised grace that transforms presence into artistry, and artistry into presence.

[1] Negishi Shingorō, Gekiken Shinan. Self-published, August 1884.

[2] Takano Sasaburō, Kendō, 1915, pp. 199-200

No comments yet.