Budo Beat 24: For Whom the Bell Tolls

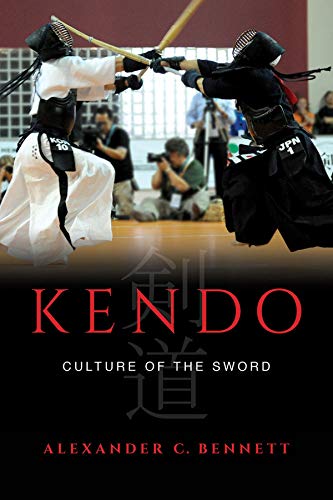

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

There comes a moment in every kendo practitioner’s life when you realise the sword cuts both ways—literally. The Japanese have a word for this particularly troublesome phenomenon: ai-uchi (相打ち), which loosely translates as “mutual strike”, though in reality, it’s something closer to “mutual destruction.” Not quite as cheerful, admittedly, but significantly more accurate.

Ai-uchi is that instance when two opponents land their decisive blows simultaneously, a situation poetically encapsulated by an old verse.

“Which shall we call the victor, which the defeated,

in this mutual striking of perfect simultaneity?”1

It’s like two sprinters crossing the finish line neck-and-neck, with only a thousandth of a second separating them. But in kendo, there’s no photo finish, no instant replay. Just two people showing zanshin—continued physical and psychological vigilance—equally convinced they’ve won, and equally baffled when either or neither gets the nod from the judges. It is, however, this very instant of ai-uchi that draws gasps of admiration and appreciation from onlookers, much like a sudden flash of lightning illuminating a storm-darkened sky—a dramatic and beautiful moment cherished by kendoka.

How cherished? A passage from Kubota Sugane’s Kenpō Kisoku Jōmoku Kuden sums it up nicely: “When one boldly resolves to strike courageously, prepared even for mutual strikes, victory often results. And if victory is not gained, dying thus is no personal disgrace; others who witness will commend one’s bravery.”2

Readers may have heard of a similar term ainuke (相抜け) from early-modern swordsmanship used by Harigaya Sekiun (?-1663), and is said to express the ideal form of an encounter according to Mujūshin-ken (“No-Abiding-Mind Sword”)—the fundamental principle of his school. Unlike aiuchi, where both parties are wounded or killed in a mutual strike, ainuke refers to a parting in which neither side is harmed, each having caused the other to strike at emptiness. In fact, among those who have reached a higher state of mastery, ainuke implies an even subtler exchange: each sensing the other’s capability before blades are even drawn, leading both to sheath their swords without engaging in combat. The fight that is settled without actually fighting…

Another old classic martial arts treatise, Kenpō Sekiun-sensei Sōden, written by Sekiun’s student, Odagiri Ichiun,3 states: “The true spirit of military strategy, originally, has nothing to do with winning or losing. Above all, in my own view, I consider aiuchi—a mutual strike—as the ultimate form of fortune.”4

This quandary is not merely academic. It represents the razor-thin margin separating competence from mastery, especially when you find yourself vying for the exalted 8-dan—a rank so notoriously difficult that passing it is akin to finding an honest politician or spotting a unicorn sipping cappuccino on the Kamo River in Kyoto.

Recently, I found myself in precisely this predicament. Ai-uchi was the iceberg to my titanic efforts, a subtle reminder of how delicate, how ruthlessly exacting, kendo can be. When one reaches for the pinnacle of this art, subtlety is everything. There’s no room for hesitation, and ironically, no space for reckless bravado either. It’s a game of calculated courage, where the heart must throw itself into battle with absolute commitment, ready for victory, accepting—no, embracing—the possibility of annihilation.

As evidenced above, the masters of old were deeply conscious of this truth. According to popular renditions of their duel in kabuki plays, novels, and movies, Miyamoto Musashi’s legendary clash with Kojirō on Ganryū Island illustrates this perfectly. Their confrontation was portrayed not simply as a display of skill, but a lethal contest where timing and commitment were everything. Had their strikes genuinely landed simultaneously, both could have been gravely injured or killed outright. In these dramatic retellings, Musashi’s decisive timing ensured his survival by the width of a hair, immortalizing his name while Kojirō’s destiny was sealed in the sand. Such is the unforgiving precision depicted in these narratives of swordsmanship.

This stark, decisive nature of genuine swordsmanship informs modern kendo profoundly. Ai–uchi encapsulates the essence of the modern discipline’s philosophy—it’s not about avoiding damage entirely (though that would be nice), but rather accepting that victory often demands vulnerability. As another old maxim states: “Let your opponent slice your flesh, so you may cleave their bone.” It’s vivid, a touch gruesome, but undeniably instructive. Come to think of it, Musashi said something along these lines.

In any case, my recent 8-dan examination was yet another reminder of this principle. I’ve had some time to think about my performance and what was missing. Despite rigorous preparation, extensive training, and enough self-assurance to power a small city, I still found myself dancing delicately, a little too timidly on the edge of ai-uchi. Each encounter was an exercise in balancing courage with caution, aggressiveness with awareness. Too careful, and you’re passive; too reckless, and you merely trade blows, cancelling each other out in the judges’ eyes.

Trying to get my head in the right space before the second round of the 8-dan examination in Kyoto recently…

There’s a curious irony to all of this. The very courage required to achieve victory through ai–uchi demands the acceptance of potential defeat. You must move past the fear of getting hit, past the fear of injury—past fear itself. It’s about fully committing to the attack, knowing you might be wounded in the process, but believing that your strike will carry greater meaning. It’s a paradoxical leap of faith, trusting that by embracing mutual destruction, you might actually emerge victorious. Ai-uchi is not just a tactical consideration; it is an existential declaration, a statement of profound personal courage and spiritual clarity.

Even today, modern kendo matches hinge on this timeless principle. Those who can execute attacks fearlessly, embracing the possibility of simultaneous blows, often find themselves standing in victory. Those overly wary of the incoming strike usually hesitate and falter.

As feedback from my recent examination, one of the examiners told me the following: “I imagine the second stage felt particularly tough. I think the examination ultimately comes down to two main points: whether you can control your opponent, and whether you can fully commit to your technique. Either way, ai-uchi is the key. Wishing you strong and spirited training as you prepare for the next one.”

So, as I step back into the dojo and ready myself once again for another run at the elusive 8-dan, the principle of ai-uchi is very much front and centre in my mind. I tell myself before each keiko that I will step onto the floor, fully committed, unafraid of being hit. Victory or defeat, the line between them has always been paper-thin. What matters is not escaping unscathed, but facing the strike with the kind of courage that turns a mutual clash into a personal triumph.

Because in the end, the lesson of ai-uchi is profoundly human: life itself is a series of mutual strikes, where we risk getting hurt every time we step forward. But step forward we must—decisively, bravely, unflinchingly. And who knows, perhaps next time the bell tolls simultaneously, the examiners will see the victor standing before them and put that ⭕️ next to my name 😀 Now, where’s that unicorn?

- (いづれをか 勝ちと定めむ いづれをか負けと申さむ あいのあいうち: Izure o ka, kachi to sadamemu, izure o ka make to mōsamu, ai no aiuchi) in Hoshi Chiyuki et al., Kana Kendō Hyakushu (Suishinsha, 1939), p. 6 ↩︎

- https://kokusho.nijl.ac.jp/biblio/100338191/1?ln=en ↩︎

- Also known as Koidekiri Ichiun (1630-1706). ↩︎

- Contained in Bujutsu Sōsho (Kokusho Kankōkai, 1915), p. 274 ↩︎

No comments yet.