Budo Beat 43: Building my Dojo in a Forgotten Valley

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

For close to three decades, I’ve called Uji home. It’s an ancient city that never quite lets you forget you’re in Japan. Maybe you’ve heard of the Tale of Genji? Well, it was written in my backyard. The Uji river cuts through the city like a beautifully polished blade, the tea fields in the surrounding hills roll in slow green waves, and history really does cling to everything like mist. It is a special place. Perhaps its most famous institution, apart from the world famous Uji green tea, is the Byōdōin temple, which adorns the ubiquitous ten-yen coin.

And, in a quiet valley, in a place called Kasatori right on the outskirts of Uji, I’m about to build a new dojo. The land clearing started last week. I’m going to call it Jigokuden (自極殿). Literally it means the “Hall of Self-Mastery”, though “Jigoku” with different kanji (地獄) also happens to mean “hell”. More on that in a minute.

The little hamlet of Kasatori was amalgamated into Uji City in 1951, but its history goes back well over a thousand years. It’s divided into two parts, Nishi Kasatori to the west, still lively with the hum of tractors and the chatter of an old primary school (albeit with only a small handful of pupils); and Higashi Kasatori to the east, where time seems to have just packed up and left.

The east side, where the dojo will stand, is a narrow valley wrapped in mountains and trees. A few old farmhouses hang onto the hillside like stubborn memories. When the wind slips through the cedars it really does sound like a long, quiet sigh. Bugger all traffic. Not a flicker of neon, or even a vending machine. No city hum. And absolutely no one to complain when the morning kiai battle cries start cracking through the valley, which they will. It is about as perfect a spot for a dojo as I could hope for.

There are only fifteen residents here, most well into their late eighties, and they seem genuinely thrilled that a dojo is coming to their forgotten corner of Uji. I have been assured there will be NO noise complaints. To be fair, I suspect most of them can barely hear the temple bell, let alone a few enthusiastic kiai. In a strange way, that makes the whole thing feel even more right.

The hushed environment, however, hides a fascinating history that runs very deep. Archaeologists from the Uji City Board of Education dug through the soil here in the 1990s and found traces of a thriving community dating back to the Heian period (794-1185). Earthenware shards, irrigation channels, and terraced paddies told the story of a landscape shaped by both sweat and Buddhist rites. Kasatori once formed part of the Daigo-ji Temple’s vast shōen network. Shōen were private estates that emerged during Japan’s Heian period, granted to temples, shrines, or nobles, and largely exempt from imperial taxation. They became both economic engines and symbols of shifting power away from the central government.

The monks of Daigo-ji oversaw these fields, gathering rice and tending shrines in a rhythm that tied the land to the temple’s fortunes. The excavation report called Kasatori a “temple farm,” a practical hub that helped keep medieval Kyoto fed and functioning. The dojo will rise on soil shaped by long, steady work and the kinds of moments that don’t make grand histories but still matter.

If the archaeology gives Kasatori its bones, the myths give it a heartbeat. Just a 20-minute short walk up the mountain to my east is Iwamadera Temple. It is located on the slopes of Mt. Iwama, 443 metres above sea level, on the border between Ōtsu City in Shiga Prefecture and Uji City in Kyoto Prefecture, and is known as Iwama-san Shōbō-ji. It is the twelfth temple of the Saigoku Thirty-Three Kannon Pilgrimage and home to the Asekake Kannon, the “Sweating Kannon” (Goddess of Mercy). The story goes that this Bodhisattva descends into the 36 hells each night to rescue tormented souls, returning to the temple drenched in divine sweat. See where I’m going with “Hell’s Den”?

The Asekake Kannon’s legend sits within a much larger map of devotion. The old Saigoku Kannon route cut straight through Kasatori on its climb toward Iwamadera, and travellers moved along these same tracks long before anyone imagined a dojo here. Training in this valley means moving through the same contours and distances that shaped their journey, letting the place speak in its own steady way.

Next to the main hall stands Bashō’s Pond (Bashō no Ike), said to be where the famed poet Matsuo Bashō once secluded himself to engage in spiritual practice and attain poetic inspiration. Tradition holds that it was here he composed his most celebrated haiku:

Furu ike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizu no oto

“An old pond—

a frog leaps in,

the sound of water.”

The pond remains to this day, quietly preserving the echo of that moment and Bashō’s presence on the mountain.

Climb the mountain road to the west of my land, and you soon reach Seiryūgū Shrine, dedicated to Seiryū Gongen, the guardian deity of Daigo-ji. She’s tied to Juntei Kannon and Nyoirin Kannon, and in older tales appears as a small golden serpent riding a great dragon. The whole area carries the feeling of a place where people once watched the land closely for signs like dragons in the clouds, spirits in the wind, meaning in the movement of water. It’s all here if you know how to look.

And there’s more! Ever heard of tengu? They are the tricksters of Japanese folklore, red-faced mountain dwellers who test human arrogance and, occasionally, reward persistence. Around Kasatori there are still places tied to these legends, such as the crag known locally as Tengu Iwa and the ridge path called Tengu Saka, where villagers once claimed to hear eerie flute music on foggy nights. Tengu are also tied to swordsmanship. Old tales have them tutoring wayward warriors in the kind of precision and awareness that scrolls can only hint at. Their lessons are never gentle, and they are never wasted. And the thought that these characters from mountain lore might be lurking in my own backyard feels like a gift. If you are going to build a dojo, having a tengu or two in the neighbourhood is not a bad start.

Peaceful though it is now, Kasatori’s past also has a whiff of intense violence. Local lore claims that retainers of Taira-no-Kiyomori fled here after the Genpei War, building a small temple called Daitoku-ji to mourn their dead. Nothing of it remains above ground, but excavations uncovered fragments of stone walls and gate foundations that hint at a defensive outpost hidden deep in the woods. Even when individuals vanish from the grand narrative, the landscape sometimes remembers them. This is part of the beauty of Kasatori.

The 1998 report by the Uji Board of Education also records unrest here during the Ōnin War and later skirmishes. Kasatori might look peaceful now, but the soil remembers moments when people fought, hid, and held on. It is not a headline place in history, yet these quiet corners tell the real story of Japan. They show where ordinary lives pushed through upheaval, rebuilt what they could, and left traces that still surface if you pay attention.

So, back to Hell’s Den, Jigokuden. The name is not for show. It is my nod to the long, slow grind that makes budo what it is. No one starts graceful. It is a hell fo a grind. But the sweat is part of the path. The Asekake Kannon sweats out of compassion. We sweat because repetition burns away the clutter until only intent is left. Every keiko is a small plunge into that heated forge. It is demanding, but strangely liberating. That is why I chose the name. And that is why the real meaning of the kanji, the Hall of Self-Mastery, feels exactly right.

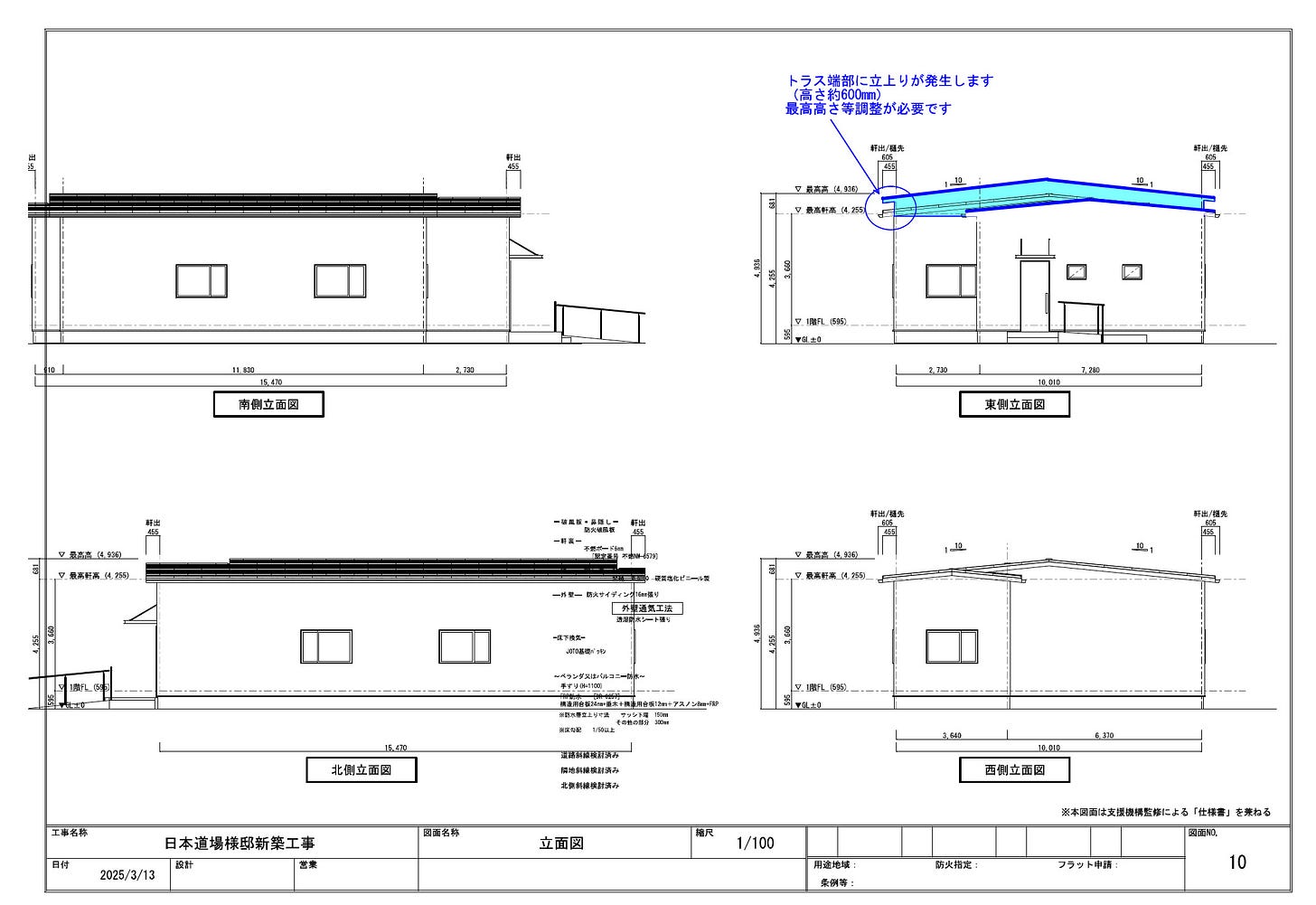

The plan is simple. The dojo will sit low on the slope at the bottom of the valley, built with modern materials but shaped to fit the place rather than shout over it. I’m certainly not trying to build a gaudy landmark. I want to keep the thread going. Daigo-ji monks oversaw these fields. Pilgrims walked the Saigoku route through here. Warriors nursed their wounds in the trees. Kasatori has always been a place where people pushed on. Jigokuden will be another layer in that long stack of human effort. That is my hope, anyway.

Sometimes it strikes me how unusual this place is, where the old world and the modern one sit side by side without competing. One moment I am walking past the new Nintendo Museum in my Uji neighbourhood, and the next I am holding what seems to be a shard of Kamakura pottery that turns up in the soil. Living here in Uji makes it clear that progress does not erase anything. It simply sits on top, one layer after another, and every so often the older layers make themselves known.

As for the picture in my head… When the dojo opens in early 2026, I can already hear the first kiai carrying across the valley. Somewhere beyond the ridge the Seiryūgū Shrine will pick up the vibration, the Asekake Kannon will register it in that quiet way deities do, and a tengu might pause just long enough to acknowledge the noise before getting on with whatever tengu get up to. And, hopefully give me some kendo pointers! For the sound of shinai will settle into the slopes, becoming part of the place rather than trying to impress it. Out here the past never really goes anywhere. It just waits for you to notice it. Training in this valley will not feel like starting something new but more like joining a rhythm that has been moving through these hills for a very long time. That is what Jigokuden is meant to hold. Not drama, not hardship for effect, but the steady work of learning something real and leaving behind a mark that feels honest to the place. I’ll keep you all updated with progress.

No comments yet.