Budo Beat 44: Fūkaku and the “Big 8”

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The late, great Inoue Yoshihiko‑sensei (Hanshi 8th Dan). Years ago, when he came to New Zealand for a seminar, we checked him into his hotel after a long flight. Nothing dramatic happened. He just walked in and headed to his room with that quiet, unmistakable Inoue‑sensei swagger. A few minutes later the hotel porter marched back over to us, eyes wide, and said, “Who the hell was that?” We asked why. He leaned in and whispered, “There’s just something… really freakily cool about that dude. What is he, some kind of… priest?”

We could only laugh. “Kind of, mate.”

That, right there, is fūkaku. He didn’t have to swing a sword or say a word. He just walked past the reception desk and the bloke in charge of luggage starts questioning the nature of existence.

This is one of the great paradoxes of fūkaku. The deeper it is, the less a person has to show. Beginners show everything, even the things they are desperately trying to hide. Intermediate practitioners learn to hide a few things and show others. But senior practitioners reach a point where there is nothing left to hide or show. They simply exist in their kendo (or other budo). The performance disappears, and what remains is the natural way their body and mind move together. Nothing fancy or particularly mysterious. Just a kind of honest, balanced movement shaped by years of practice.

Looking across the generations of great teachers I’ve encountered, the ones who left the strongest impressions on me had very different physical styles, but all possessed unmistakable “fūkaku”. Some were big buggers, some little old ladies. Some explosive, others impossibly still. Some would overwhelm you with ki before you even stepped into range. Others would barely move, yet somehow you felt everything collapsing around you as you tried to approach. What united them was not what they did, but what they no longer needed to do.

Budo has many words that sit just beyond easy translation. I think fūkaku (風格) is one of these elusive terms. Literally, it combines “wind” (風), meaning in this context atmosphere, breath, or the felt quality of something, with “form/frame” (格), meaning the structure or inherent character that gives something its proper shape. It seems simple enough. “Style”, “dignity”, “bearing”, “presence”… But as anyone who has spent time inside a dojo knows, none of these English equivalents quite grasp what fūkaku actually feels like when you sense it emanating from someone before a technique has even begun to take shape.

I’ve been thinking a lot about fūkaku for the past few days after my recent 8th Dan examination. I didn’t pass, which is no surprise to anyone who knows how brutally high the bar sits for that level! As usual, less than 1% pass rate… Anyway, one of the examiners pulled me aside after it had all finished and said, “Alex-kun, you looked really good out there mate! And you had genuine fūkaku going on…”

In the middle of the emotional muddle that always follows these examinations, that comment landed in an interesting place. Encouraging? Yeah. Humbling? Yeah, I guess. Still not enough to pass, though! But it pushed me into a long reflection about what fūkaku really means, why it matters. Am I on the right path?

Anyone can pretty much recognise a sharp men, a clean kote, or a precisely placed tsuki even after only a few months of practice. But fūkaku is something very different. It rests in the shape of the person, not the technique. It is the quality that remains after all the unnecessary motion has been stripped away, leaving only essential form supported by years of discipline, failure (and yet more failure), stubbornness, introspection, and the slow forging of spirit.

It is tempting to think that fūkaku arrives at a certain dan grade, as if the number creates the person. But the reality is almost the opposite. People who exude fūkaku are the ones who make their dan grades look insufficient. Their presence overshadows the certificate hanging on the wall. When they stand ready, even before they bow, there is an unmistakable feeling that something is different. They are not imposing themselves and they are not trying to intimidate. They are simply there, completely, without hesitation or pretence. That completeness, I think, is the essence of fūkaku.

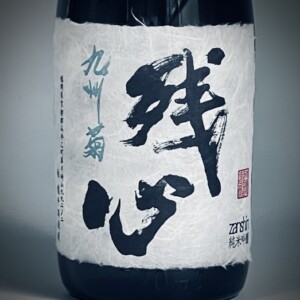

One way I’ve had fūkaku explained to me is to “the feeling of watching an expert calligrapher pick up the brush”. Before a single stroke is made, the whole room feels different. The brush, the ink, and the paper have not changed. What has changed is the atmosphere generated by the practitioner’s accumulated depth. Budo has the same quality. Before any cut or thrust is made, the state of the person determines the state of the encounter. Someone with fūkaku creates a kind of silent order. It’s as if their movements are calm without being passive, sharp without being frantic, and powerful without relying on force. Everything appears simple, but that simplicity has taken decades to construct.

Terayama Tanchū, a master of the brush and the blade, embodied true fūkaku. Though I was never formally his student, he taught me countless things in his dojo, especially about Yamaoka Tesshū. Having trained under two of the great Zen teachers of the twentieth century, Ōmori Sōgen Rōshi and Yokoyama Tenkei, he reached enlightenment at thirty-six and went on to become one of Japan’s foremost Zen calligraphers.

My own relationship with this idea of fūkaku has shifted over time. When I was younger and I went up against people who had what I now understand as fūkaku, I didn’t have a word for it. I just felt it. Something in the air would change. Before they even moved, there was this quiet pressure, this sense that they were already one step ahead simply by being themselves. Back then I would think, “What the heck is this feeling?” without knowing how to describe it.

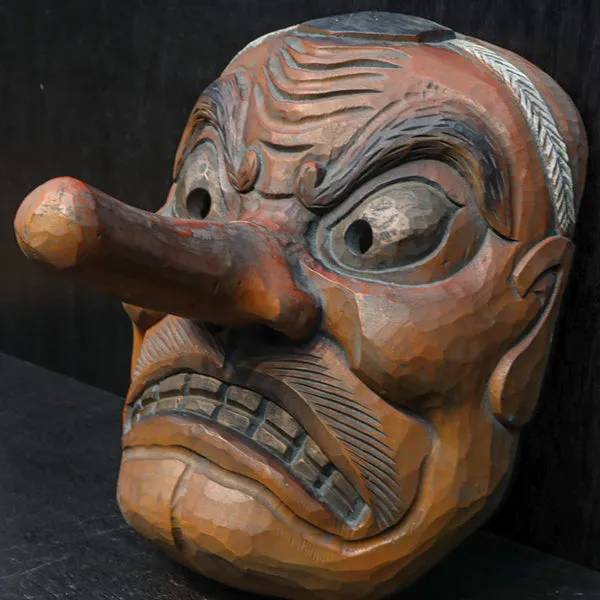

Now, I have the vocabulary. When I was young, dumb and full of energy, I imagined that ‘presence’ came from physical strength. Swing harder, move faster, dominate the centre, break the opponent’s rhythm, push relentlessly, and the feeling of authority would follow. Of course, this is an important step, but strength alone never created presence. If anything, it produced impatience, and impatience is the enemy of composure. Later, I thought fūkaku might come from impeccable technique. Clean lines, perfect posture, and textbook strikes would produce the right atmosphere. But again, this was incomplete. Beautiful technique without internal maturity is like a finely carved mask propped upright with no one behind it. The lines are exquisite, the colours impeccable, but there is no breath inside it, no warmth, no intention. It looks complete, yet nothing truly lives within it.

True fūkaku only starts to take shape when a person’s outer technique and inner self begin to align. This is why it often emerges later in life. It requires a mixture of experience and exhaustion. After enough rounds of keiko, and enough struggles that force you to confront your own habits, a person begins to reveal themselves through their kendo in a more honest way. The unnecessary peeling away with the essentials remaining. I think that’s about where I’m at now.

In that sense, I suspect this is what the examiner in question was responding to after my failed attempt. He did not see perfection. If he had, I’d have passed! But he saw something like coherence, a relationship between intention and action that felt genuine and consistent. That in itself is enough to sustain a person through another cycle of practice and reflection. Sigh 😉

I’m committed to keeping my work freely accessible to all budo enthusiasts, wherever they are. If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve found here and would like to support my ongoing efforts and projects, “buying me a coffee” (beer actually), or my books, would make a world of difference. Cheers!

Once, Inoue-sensei explained the characters of “fū” and “kaku” in a way that ALMOST made everything click for me. I didn’t have a grasp of the finer nuances of Japanese terms, so he dumbed it right down. “Fū”, he said, “is the same character used for kaze, meaning wind. Not wind as in weather reports, but the kind of light sensation you feel on your skin. In other words, movement, breath, atmosphere. It’s the subtle quality that gives something its mood or flavour.” By contrast, “kaku” means the frame or structure of a person. That is, “dignity, posture, the solid, steady part that doesn’t wobble under pressure.” So, when you put them together, fūkaku simply means this: the ‘wind’ of someone’s atmosphere carried by the ‘frame’ of their character. Well, it kind of made sense when he explained it to me in those terms.

He pointed out that fūkaku emerges from the alignment of ki‑ken‑tai (spirit–sword–body). “It’s not a matter of hitting by any means necessary, or chasing small victories. It is the disciplined pursuit of strikes that carry hin’i (refined dignity, 品位) and hinsei (moral character, 品性). In other words, technique must not only be correct, but must feel morally and aesthetically sound. This is why true fūkaku can determine the outcome of combat even before technique fully enters the exchange. Presence shapes perception. Presence shapes opportunity. Presence shapes victory.”

Still a little confused, when I asked him more about this “kaku” thing, he said “It’s your inner backbone. Not the bones in your spine, but the part of you that stays steady when everything else is falling to bits. It’s your core.”

And the “fū” thing, he explained, extends outward into the atmosphere of entire groups. “In Japanese, people talk about a household having its fū (its “feel” or “character”), a dojo having its fū, a school having its fū. Even an era or generation can be recognised by its fū. And when the fū of politics declines, the fū of the whole country declines with it. In this sense, fūkaku is not an ornamental idea. It is a stabilising force. When embodied at a high level, it influences not only individuals, but the tone of communities.”

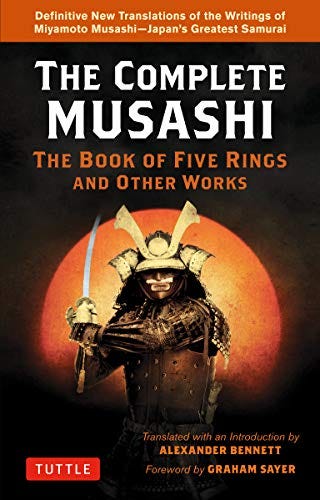

Bloody hell! Come to think of it, Miyamoto Musashi has and entire chapter dedicated to this in the Book of Five Rings! It all started to connect.

All of this reinforces the core point: budo WITHOUT fūkaku is nothing more than hitting. Budo WITH fūkaku is a way of shaping the mind and revealing one’s character. Practising with this awareness means moving beyond the usual cycle of “striking and being struck” and into the deeper territory of what Inoue-sensei constantly advocated: “kokoro no budō (budo of the heart) ~ the budo that refines, rather than merely competes.”

Budo is full of ego traps: trying to win, trying to look good, trying not to disappoint, trying not to embarrass ourselves. All of these shape our behaviour, but they also hide the fact that budo is ultimately an attempt to understand our own minds. A person with fūkaku is no longer trying to manage impressions. They are not hiding their fear, nor trying to project invincibility. They simply stand as they are, fully engaged, fully aware, and fully responsible for the moment. This genuine presence affects the opponent’s body without a single visible action. It is the quiet form of psychological pressure that separates the Way of budo from mere technique.

Senior examinations like 8th Dan are specifically searching for this quality, because by the time someone reaches that level, everyone can already strike a cracking clean men. That is not the question anymore. The question becomes: what kind of person appears when you do kendo?

Allow me to elaborate. At 8th Dan in kendo, the pass rate is often less than one percent. Everyone on the floor has decades of practice behind them. Everyone has good technique. Every single one of the candidates has mental strength. But not everyone has polish in their spirit. Not everyone has the kind of presence that fills the interval with aura. In other words, not everyone has fūkaku. To be told that you have even the beginnings of it is less a compliment about skill and more a gentle hint that something in your kendo is finally growing up a little, even if, like me, you still walk off the floor clutching that fail slip and wondering if the judges were watching the same bloke you thought you were being. It’s the kind of thing that can’t be manufactured or mimicked. It has to be lived.

Thinking about fūkaku also brings me back to something I see a lot across the budo world. People often assume that high-level budo is about sublime complexity, but the opposite is true. At the top, everything simplifies. Movements shrink and the mind steadies as beauty is found in minimalism. Opportunities are no longer created through speed but through clarity. The strike becomes the natural conclusion of a situation, rather than an interruption. I’m thinking that this simplicity is one of the hallmarks of fūkaku. Athletic complexity might get a few oohs and aahs, but simplicity is the bit that makes you shake your head and go, “Well of course… you idiot… why didn’t you just do that in the first place?” When I do eventually pass, I’m sure that’s what I’ll tell myself…

I should add, there is also a moral dimension to fūkaku. The word carries connotations of dignity, but not in the sense of stiffness or self-importance. It is more like the dignity that comes from living in alignment with one’s values. In this sense, it overlaps in some ways with the concept of “kigurai” (You can read about this in a previous blogpost). It comes from treating opponents as partners in growth, respecting teachers, demanding honesty of oneself, and understanding that victory is meaningless if one leaves the dojo unchanged. Budo, at its highest level, is a form of self-examination. The atmosphere a person carries reflects the state of that examination.

For me, said examiner’s comment served as a bit of a reminder to me that even when we fall short of our immediate goals, the long path continues to form us in more subtle ways. Passing or failing is never the full story. The shaping of character is slower, quieter, and often only becomes visible to others before it becomes visible to oneself. If someone else saw fūkaku in my kendo that day, then perhaps the long years of training and refining have begun to consolidate into something coherent.

Well, I hope so, at least! That, in itself, is enough reason to step back into keiko with a fresh sense of purpose. If we cannot always control the outcome, we can at least shape the person who continues to walk onto the floor. And that, I suppose, is the real meaning of fūkaku. Not a style, or a pose or technique, but the honest form of a life spent in practice becoming visible for a few fleeting moments between one bow and the next…

Hmmm. Now that I have finished over‑philosophising and squeezing whatever positives I can out of the whole exercise, it’s probably time to get back on the horse and into the dojo. Onwards and upwards, as they say.

And since fū also shows up in tai-fū (typhoon, 台風), there’s probably a lesson in that too. The same “wind” that can be gentle enough to rustle the leaves can also pick up your roof and send it to bloody Osaka. Atmosphere is unpredictable. Presence can be too. Some days you feel like a calm evening breeze, other days you turn up to keiko feeling like a category‑five shambles.

Either way, the wind keeps moving, and so should I. Hopefully next time it blows me somewhere useful instead of straight back onto my arse. But even if it does, at least I will know which direction I am supposed to be facing. And that, for now, is plenty.

No comments yet.