Budo Beat 14: Budo Without Barriers

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

Zatoichi, the fictional blind swordsman was a master at using what he had, rather than lamenting what he lacked. And that’s the essence of budo—leveraging whatever abilities you possess and refining them through dedicated practice. The wandering masseur with a walking stick that doubled as a lethal blade was a lesson in adjustment, proving that skill, perception, and sheer bloody-minded determination could cut through limitations like a well-honed katana.

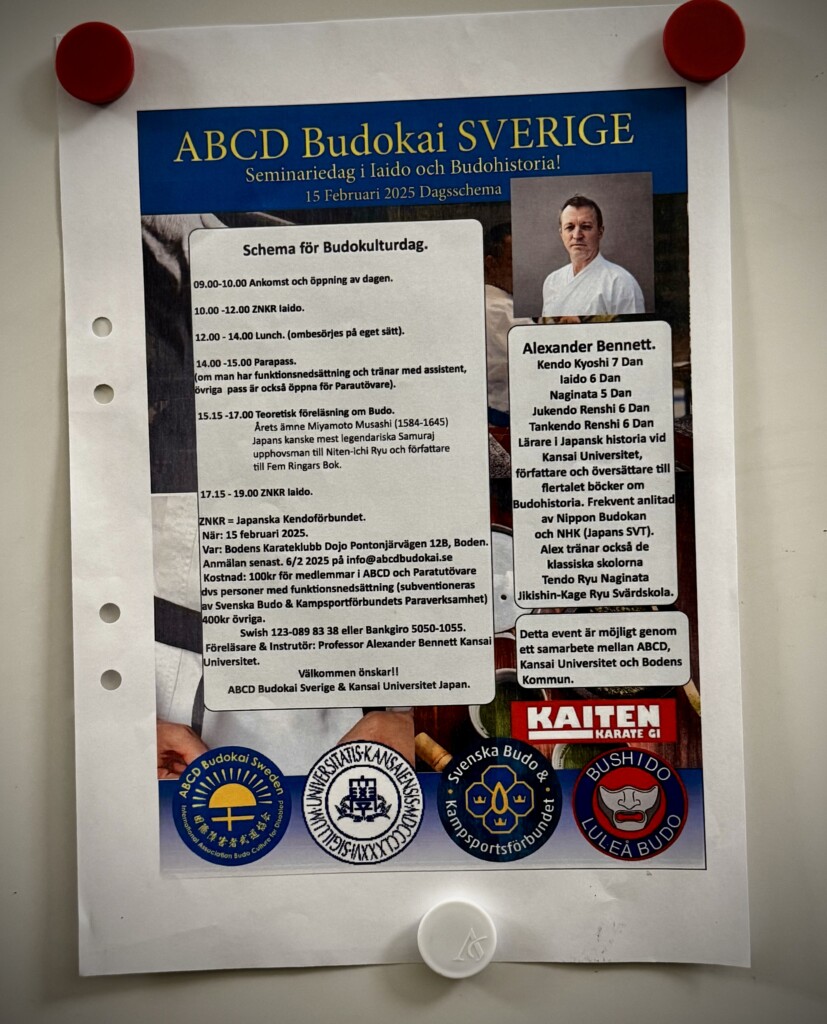

Each year, I land in Boden, a northern Swedish town where the cold could flay an unguarded cheek, but the welcome is warm enough to thaw any cynic. February rolls in, and I guide a group of Japanese students through this snow-laden world to see how Sweden weaves together its schools, sports, and welfare. The Association for Budo Culture for the Disabled (ABCD) arranges everything for us and also offers a rare window into their discipline while I lead a one-day budo seminar—an exchange that, in its uneven generosity, leaves me feeling somewhat guilty.

It isn’t just any budo seminar—the focus as always is “para budo”, the modified form of budo practice that makes room for those with physical and cognitive challenges. Here, the spirit of budo isn’t confined to those with six-packs, perfect reflexes and well-oiled joints (God knows I don’t have any of those either…) It’s for anyone with the drive to train, improve, and adapt techniques until they work for them—no matter their circumstances.

In more concrete terms, para budo is the practice of traditional and modern martial arts adapted for individuals with disabilities. It encompasses a range of disciplines, including judo, karate, and other disciplines modified to accommodate practitioners with various physical and cognitive conditions. Para budo is not merely a set of altered techniques but an inclusive philosophy that recognises the martial artist’s skill, determination, and adaptability regardless of limitations. Rooted in the values of perseverance, discipline, and respect, para budo ensures that martial arts remain accessible to ALL individuals, allowing them to engage in combat training, self-defence, and personal development.

Boden is already a stronghold of para budo, with most practitioners engaged in customised judo and/or karate. The principles of balance, movement, and controlled technique in these arts lend themselves well to modification. At the heart of it all are dedicated teachers like Pontus-sensei who was at the helm of establishing ABCD. Niklas-sensei, who runs classes at the local high school, teaching special needs pupils karate each week. Then there are Margareta-sensei, and Johannes-sensei, who lead para budo classes at the local club, catering to people of all ages and challenges. Their focus is on having fun, developing concentration, making the most of what you’ve got and experiencing the thrill of participation.

I introduced something different from the usual unarmed budo—iaido, the Japanese martial art of drawing and cutting with a sword in one fluid motion. It emphasizes precision, control, and awareness, practiced with the intent of responding to imagined opponents. So, out came the bokutō (wooden swords) and plastic saya (scabbards)—simple, safe tools that allow students and teachers to experience the core movements of drawing, cutting, and re-sheathing a sword without the risk of unintended battlefield surgery!

Para iaido, like all adaptations of budo, demands a mental gear shift and some technical modifications. Traditional iaido assumes practitioners can kneel, stand, and pivot with the grace of a kabuki performer. With a bit of adaptation, the principles—balance, control, and precision—translate very well.

I noticed some students took to it immediately, their movements guided by an innate sense of rhythm. Others had to work harder, and watching them push through that struggle made their achievements all the more rewarding. One student, who had difficulty with left- and right-hand coordination, shared with me that smoothly returning the sword to the saya was a revelation—it gave him a sense of challenge and control. Another, who struggled with balance, told me how the deliberate stepping of iaido helped him feel more stable, more in command of his own movement.

That was the beauty of it—iaido, when approached without the kind of obsessive scrutiny that would make a watchmaker weep (as it normally is), becomes a way to discover and refine one’s latent physical abilities. In fact, the various limitations of the practitioners only underscored how immensely effective it is at keeping people active, engaged, and challenged.

Interestingly, those of us who have been training in budo for a lifetime also find ourselves constantly adjusting. As physical power diminishes, eyesight fades, and joints creak with age, we too must modify our practice to continue participating. Lifelong budo practitioners are always refining their approach, proving that adaptation isn’t just a necessity for some—it’s a reality for all of us.

People often ask what they need to do to teach students with unique challenges. The answer is simple: just use common sense. There is no one-size-fits-all method. It’s about tailoring certain aspects of training in terms of communication, intensity, safety, and technical difficulty to create an encouraging environment for the student to participate. Adaptation is the key, and as long as the instructor is willing to be flexible and observant, it will all fall into place.

As great as it sounds, para budo certainly faces a range of challenges. Chief among these is competition and gradings. Budo has always had a competitive streak—whether in camaraderie or rivalry. But how does one fairly referee a “para karate” kata match where one competitor has limited mobility while the other navigates the challenge of restricted sight? The question itself highlights the complexity of ensuring an even playing field and underscores the need for referees and examiners to be thoroughly educated in recognizing skill, intent, and effective execution beyond surface-level appearances.

Bias is another massive issue. Some sensei hesitate to award ranks to para budo students, as if a black belt earned with a modified technique is somehow less valid. There is also bias at the national and international federation levels, as well as among guardians, parents, and even some practitioners themselves. Many believe that budo is simply too dangerous or risky to be customised for those with physical or cognitive challenges. This perception, however, is misguided. The truth is that budo, when properly taught and modified appropriately, provides immense benefits—improving physical mobility, mental focus, and confidence.

The assumption that para budo practitioners cannot safely engage in martial arts not only underestimates their capabilities but also disregards the fundamental flexibility that has always been central to modern budo. The great budo masters of old always modified techniques to fit their needs.

Naturally, the keyboard warriors—those titans of the trackpad—pipe up, decrying para budo as ‘not real’ from the ergonomic embrace of their swivel chairs. They nurse the delusion that budo is a sacred enclave for the unblemished and the nimble, conveniently ignoring that the greatest masters honed their art not through physical perfection but through relentless adaptation. Budo isn’t about exclusion—it’s about making it work, no matter the body, no matter the odds. But of course, it’s easier to sneer from a safe distance than to confront the limitations of one’s own rigid mind.

Ignoramuses aside, more importantly, para budo fosters a strong sense of community. It provides practitioners with the opportunity to interact with others, push themselves in a supportive environment, and develop meaningful connections. And this exchange is mutual—para budo not only offers invaluable experiences to those with disabilities but also enriches the broader martial arts world by breaking down rigid perspectives and reinforcing the core values of respect and empathy. In a dojo where inclusivity is the norm rather than the exception, the true essence of budo—growth, resilience, mutual learning and wellbeing—becomes all the more apparent.

What’s striking about para budo dojos in Sweden isn’t just the lack of ego—it’s the sheer joy of movement. There’s no posturing, no artificial hierarchy, just the simple thrill of learning and refining. Progress isn’t measured against others but against oneself, and success is found in every breakthrough, however small. The satisfaction of overcoming personal obstacles, of executing a technique well despite perceived barriers, was tangible.

As the old Miyamoto Musashi saying goes, “Train for a thousand days to forge yourself; train for ten thousand days to refine yourself.” Musashi’s fundamental philosophy was to use whatever you have in the most practical way possible—whether it be using two swords instead of one, or simply making the most of your attributes. This philosophy encapsulates the para budo spirit—training is a lifelong process, and refinement comes not from adhering to rigid traditions but from continuously adjusting, learning, and evolving.

The iaido gig I do each year is a small but hopefully significant step in showing that even arts perceived as static or rigid can be modified. Iaido is particularly prone to focusing on the tiniest details—down to the position of one’s little toe or the exact millimetre where the blade should stop after a cut. Preoccupation with precision in budo is important, but can sometimes overshadow its essence. In para budo, the focus returns to what truly matters: the fluidity of technique, the clarity of intent, and unyielding adaptability. And the more people see para budo in action—not as a charitable endeavour but as a legitimate expression of budo—the faster old biases will crumble.

While the benefits of para budo to physical rehabilitation and therapy are undeniable, its true value lies in its ability to inspire, engage, and connect people. The cultural aspects of budo—its discipline, its rituals, its traditions—give practitioners something more than just physical improvement; they provide motivation, identity, and a pathway for lifelong learning. For individuals with disabilities, para budo is not just about adapting techniques—it is about embracing the depth of martial arts, finding confidence in movement, and being part of a tradition that stretches beyond the dojo and into everyday life.

The real test of any budo practice isn’t some abstract notion of ‘purity’—a concept so vague it could sustain endless late-night debates among those who confuse dogma with wisdom—but its ability to build resilience, discipline, and growth. Budo is movement, struggle, sweat, and persistence—and in para budo, where adaptation is necessity to varying degrees, you see it in its rawest, most honest form.

Para budo isn’t a deviation from tradition; it’s a continuation of it. The great martial artists of the past didn’t cling to rigid forms—they adapted, evolved, and made the art work for them. That same spirit drives para budo today, ensuring that martial arts remain not a closed-off relic, but an ever-relevant path for those who refuse to be excluded.

That’s what “budo without barriers” really means. Budo isn’t for the few. Budo is for everyone.

No comments yet.