Budo Beat 9: Fighting the Inner Foe ~ A Mid-January Lamentation

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

It’s mid-January 2025, and the glow of Christmas lights has faded, leaving behind a faint echo of cheer and the cold sting of resolutions unmet. Like everyone else, I welcomed the New Year armed with massive promises to myself—grand plans to seize the days ahead and emerge, somehow, shinier and better. Yet here I am, two weeks in, and I feel like the engine just won’t start. Motivation has drifted away like snowflakes on the wind (it’s bloody cold in Japan), leaving me wrestling not with external adversaries in the dojo, but with the all-too-familiar foe of my own inertia. In the language of budo, I am losing to myself.

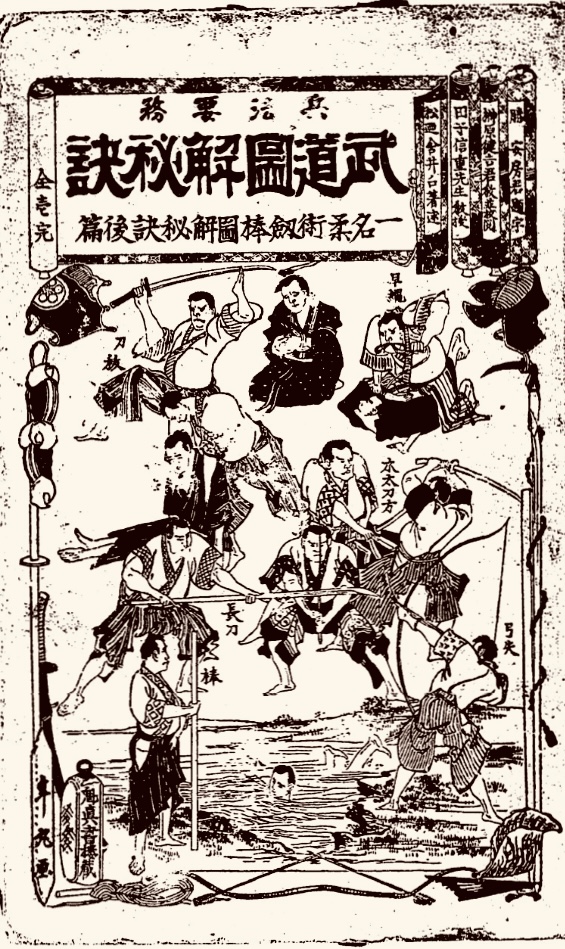

An old book in my collection offers a profound lesson:

“The impatient mind that hastens to show results forgets to surpass the self of yesterday.”[1]

This single line, I think, sums up the heart of my struggle at the moment. I’ve been so preoccupied with trying to see immediate progress—proof that my resolutions weren’t just empty words—that I’ve overlooked the quiet victories of persistence. Budo reminds us that progress is rarely flashy; it’s measured in the steady chipping away of yesterday’s limitations.

Mastery in budo demands more than skill or precision in a strike; it requires a grit-laden resolve that scoffs at mere physical hardship. Budo is not simply about strength or finesse. It is a crucible for the self, a way of life where every swing of the blade or fist, and every bead of sweat hammers away at the dross of ego, leaving behind the tempered steel of character. To buckle under the strain of practice or yield to laziness, selfish whims, or stray thoughts is to forfeit the chance at true mastery.

Speaking of hammering away, there is another teaching in a rare publication I managed to get my hands on in one of my favourite places, a Jinbochō bookshop.

“Shatter your own self with the hammer of courage—This is the true teaching.”[2]

At its heart, budo is about self-conquest. The opponent you face in the mirror—that shadowy assemblage of doubt, fatigue, and indulgence—is far more formidable than the foe standing across the dojo floor. Overcoming such inner weaknesses isn’t the work of a moment. It takes relentless hammering, the kind that transforms raw ore into a sword capable of slicing through life’s thorniest challenges. The “hammer of courage” is no idle metaphor; it’s a reminder that progress only comes to those who strike at their core with fearless consistency.

The old traditions of budo encapsulate this philosophy. Consider mid-winter training (Kangeiko), held during the coldest days of the year (like right now), and summer training (Shochūgeiko), practiced in the sweltering heat. These gruelling rituals are designed to push practitioners beyond their physical and mental limits, fostering resilience and discipline. These sessions aren’t about proving toughness for its own sake; they’re designed to push practitioners beyond their physical and mental breaking points, fostering a resilience that turns storms into mere weather. Such trials fortify the virtues of discipline and endurance, the cornerstones of the budo path.

In the end, as the cliché goes, budo is less about defeating others and more about remaking oneself. Its rigorous physical training and stern mental discipline forge a framework for personal growth. The hammer of courage, wielded with persistence, shapes a resilience that transcends the dojo. Through enduring trials, reflecting on hard-won victories and sobering defeats, practitioners of budo discover the enduring strength to meet life’s broader battles with grace and resolve. In this way, budo becomes a lifelong pursuit, as relevant in the office or home as it is in the arena of combat.

Phew… And so, as I get ready put on my jacket and prepare to head for the dojo, I remind myself that the hardest step is often the first. My bag is about to be slung over my shoulder like a reluctant ally, its contents rattling with an air of mild disapproval, as if longing for the comfort of the warm living room I’m going to leave behind. But off I will go, bolstered by the wisdom of old budo books and the faint, wry realization that sometimes, the battle isn’t won with a dramatic flourish, but with the simple act of showing up—even if you feel like a warrior whose armour is held together with duct tape and feigned optimism, like I do now.

[1] “Kuttaku wa shirushi o isogu kokoro yue, Kinō no ware ni shō o wasurete.” In Heihō Yōmu Budō Zukai Hiketzu by Inokuchi Matsunosuke, 1890.

[2] “Onore ga mi o yūki no tsuchi de uchikudake, Kore zo makoto no oshie narikeri.” In Kendō Iroha Uta Shōkai by Hashiguchi Tatsuo, 1930.

No comments yet.