Budo Beat 15: Losing Yourself

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

“Losing yourself” is not “losing to yourself”. Last week in Sweden, I had the chance to do kendo in the Luleå Bushido Dojo again. The usual suspects were there, but what caught my eye was one of the young lads from last year. He’d improved—a lot. His strikes were sharper, his footwork tighter. And yet, something was missing. That final touch, that last push. I asked him if he’d ever heard of sutemi. He shook his head. So, I explained. Sutemi isn’t just about taking a leap; it’s about throwing caution to the wind and depositing more “sacrifce” into his kendo bank. “When you go, just bloody go, boy!” Thinking about it later, I realised again: this is perhaps the hardest aspect of any budo.

At some point in life, everyone faces a moment when the only way out is through. It might come as a deadline that barrels towards you like an avalanche (the story of my life), a crisis that leaves no room for dithering, or a battle—literal or metaphorical—where the only winning move is to risk everything. In budo, this principle has a name: sutemi (捨て身), or “casting away the body.” It is the art of self-abandonment, or sacrifice, in the service of a greater goal, the paradox of ultimate risk yielding ultimate safety. And if this sounds like the sort of contradiction that fuels half the koans in Zen Buddhism, that’s because it is.

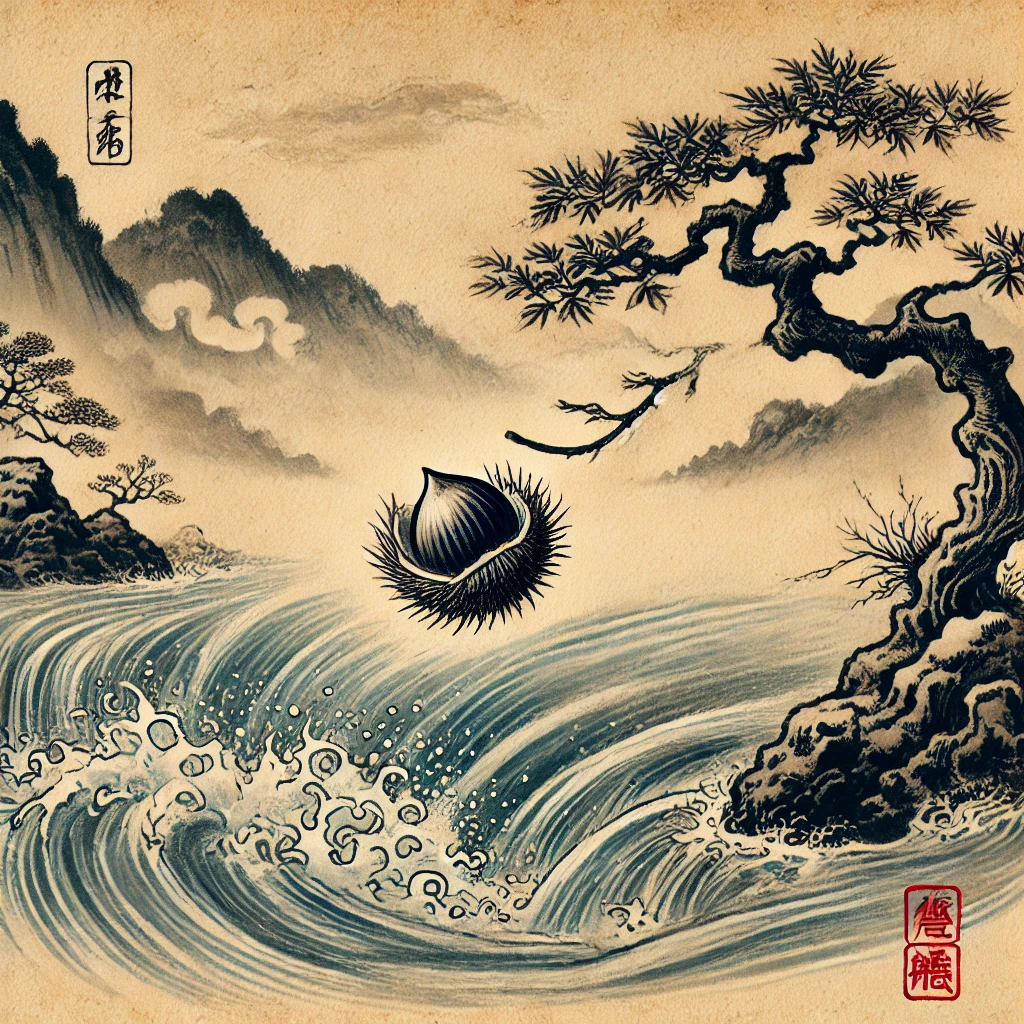

To grasp sutemi, let’s start with the image of a chestnut husk floating in a rushing stream.

The chestnut shell tossed through the river’s rapids,

Only when it lets go of its kernel can it finally rise and float. [1]

As this old poem goes, it is only when the husk has discarded its seed that it has a chance to stay afloat. In other words, by surrendering the very thing it holds most dear, it gains a new kind of freedom. This principle applies just as readily to budo as it does to life. The warrior who clings too desperately to survival is doomed to hesitate, to flinch, to fight with one foot already retreating. But the one who hurls themself forward with no thought for personal safety achieves a terrifying effectiveness. They move with a single-mindedness that turns them into a force of nature, unburdened by the paralysing weight of self-preservation.

This is not just an old samurai fantasy. Judo and jujutsu are built around sutemi-waza—sacrifice techniques—where one deliberately throws oneself to the ground in order to gain a superior position. The most famous example is the tomoe-nage, or “stomach throw,” in which a judoka flings their own body backwards, dragging the opponent with them, using the momentum to send them hurtling overhead. To the untrained eye, this looks like reckless self-endangerment. But in reality, it is a calculated trade-off: temporary vulnerability for eventual control. The best judoka are those who commit fully, who don’t hedge their bets halfway. The difference between glory and disaster is measured in millimetres and microseconds.

Kenjutsu—the predecessor to modern kendo—was never about the cautious, swashbuckling ching-chinging in chanbara movies. It was a brutal science in which the goal was to end a fight in a single, decisive stroke. The master swordsmen of old understood that the moment of attack was also the moment of greatest vulnerability. They trained to drive through hesitation, to strike in a way that made retreat impossible. Miyamoto Musashi, undefeated in over sixty duels, famously wrote in The Book of Five Rings that a warrior must be prepared to die with each stroke. Not in the sense of fatalism, but in the sense that every cut should be delivered as though nothing else mattered. The irony, of course, is that such an attitude makes survival more likely. To hesitate is to die. To embrace death is to live.

Actually, many of Musashi’s teachings are premised on the notion of sutemi. For example, in his principle of Trampling the Sword: “If you trample his sword underfoot, he will be defeated on the first attack and will not have an opportunity to make a second. Trampling should not be limited to the feet. The body is used to trample, the spirit is used to trample and, of course, the sword is used to trample. No respite should be given so that the enemy has no chance to make a second move…”[2] This is just one example of many where Musashi advocates the all-or-nothing imperative in combat.

One of my favourite anecdotes on this comes from the Hagakure, a book brimming with the kind of stark wisdom that makes you want to leap headfirst into a blizzard just to prove a point. It tells of a group of blind monks, fumbling their way across a treacherous mountain pass with all the enthusiasm of men who’d just realised they were about to star in a cautionary tale. Hesitation gripped them—until one of them slipped, tumbled, and landed with an unceremonious thud. Instead of wailing, he dusted himself off and called back up, “I worried about what would happen if I fell, and was somewhat apprehensive. But now I am very calm. If you want to put your minds at ease, quickly fall [and get it over with].” (10-125)

And that was all it took. His words cut through the fear like a hot knife through butter. The others followed, emboldened. The lesson? Fear dissolves the moment you stop clinging to it. Besides, he only dropped a couple of metres—hardly the grand tragedy he’d first imagined.

It is the shikai (四戒)—the four illnesses—that prevent sutemi from manifesting. Fear, doubt, surprise, and hesitation hold a practitioner back, keeping them from fully committing to their actions. Overcoming these barriers is what we are essentially striving for in keiko. This process is not just about technique but about cultivating the mindset that allows one to embrace sutemi without reservation.

Sutemi is not about recklessness. It is not about charging blindly into ruin but about recognising that, in certain moments, half-measures are more dangerous than total commitment. Sun Tzu advised always leaving an enemy an escape route because a trapped opponent fights with desperate fury. Sutemi is the conscious decision to enter that state voluntarily.

In the end, sutemi is about trust. Trust in your training, trust in your instincts, and most importantly, trust in the idea that commitment itself creates momentum. The judoka must trust that their throw will work. The kendoka must trust that their cut will land. The karateka must trust that their kick will connect. The moment hesitation creeps in, the moment one foot starts edging towards safety, the moment retreat becomes an option—it is already too late.

This is why, across cultures and throughout history, those who have achieved greatness have done so by fully embodying the spirit of sutemi, committing themselves without hesitation to the path ahead. They have been the ones who, when faced with the rapids of life, did not clutch tightly to what they had but had the courage to make massive sacrifices, knowing that in doing so, they would find a way to rise above the current, not just to float, but to forge their own path forward.

[1] Wada Katsunori, Seppuku no Tetsugaku (Shūbunsha, 1928) p. 146

[2] Alexander Bennett, Complete Musashi: The Book of Five Rings and Other Works (Tuttle, 2019) pp. 112-113

No comments yet.