Budo Beat 22: Dan, Not Done

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

There’s an allure, subtle yet irresistible, about the endless road in Japanese budo, to those in the know. One could (should) spend an entire life unravelling its intricacies, losing oneself in the poetry of technique, philosophy, and the disciplined pursuit of something ever slightly beyond grasp. Part of the challenge in this fascinating voyage lies the tantalisingly enigmatic, and maddeningly frustrating system of “dan” (段).

On first glance, dan might appear little more than a glorified marker of superhuman skill—the elusive “black belt” that Hollywood loves to fetishise—but its true meaning swims around in richer philosophical depths than most practitioners, much less casual onlookers, ever realise they’re paddling in. Yet there’s always another side to this particular coin, where some folks lavish upon dan an almost mythical significance it was never meant to carry.

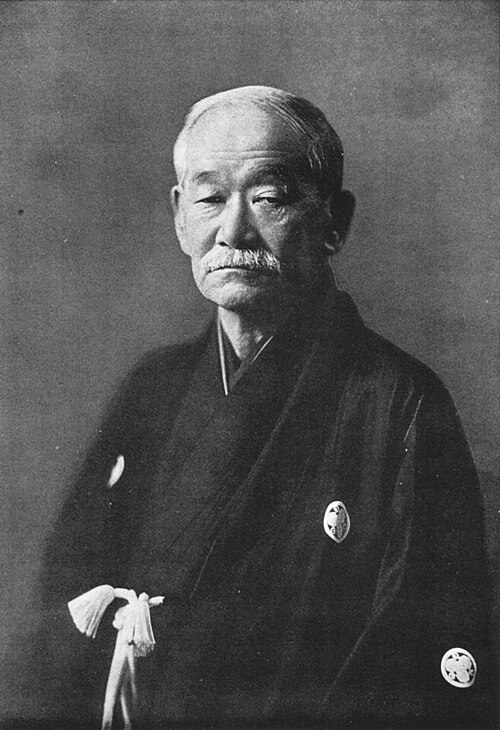

At its simplest, dan translates roughly as “step”, “level”, or “grade”. Historically, it first emerged within Japanese culture through the world of traditional board games such as Go and Shogi, indicating a player’s skill level. Kanō Jigorō, the legendary founder of judo, introduced the dan ranking system into martial arts during the late 19th century. Kanō saw clearly that structured progression through well-defined ranks could ignite a drive for continual growth and disciplined practice. His revolutionary approach soon rippled outward, sweeping through the full spectrum of budo—kendo, sumo, karate, kyudo, and everything in between. It even became the ranking system for Korean and Chinese martial arts.

In the Edo period, Japanese martial arts typically employed the traditional menkyo (licence) system for ranking practitioners. Unlike modern dan and kyū grades, the menkyo system consisted of progressive levels and accompanying scrolls of transmission—such as shoden (initial transmission), chūden (intermediate transmission), and okuden (inner or advanced teachings)—culminating in full mastery, known as menkyo kaiden. Rather than standardised examinations like in modern budo, promotion depended largely on the master’s personal judgement and recognition of the student’s development and readiness.

The widespread perception in popular culture—especially in the West—is that achieving a “black belt” equates to becoming some kind of martial arts superhuman. But anyone genuinely embedded in budo understands it’s merely an entry point into deeper, more profound learning. As many martial artists can testify, reaching your first dan (Shodan), for example, is akin to finally grasping the alphabet of a new language; only now can you genuinely begin to read, write, and explore.

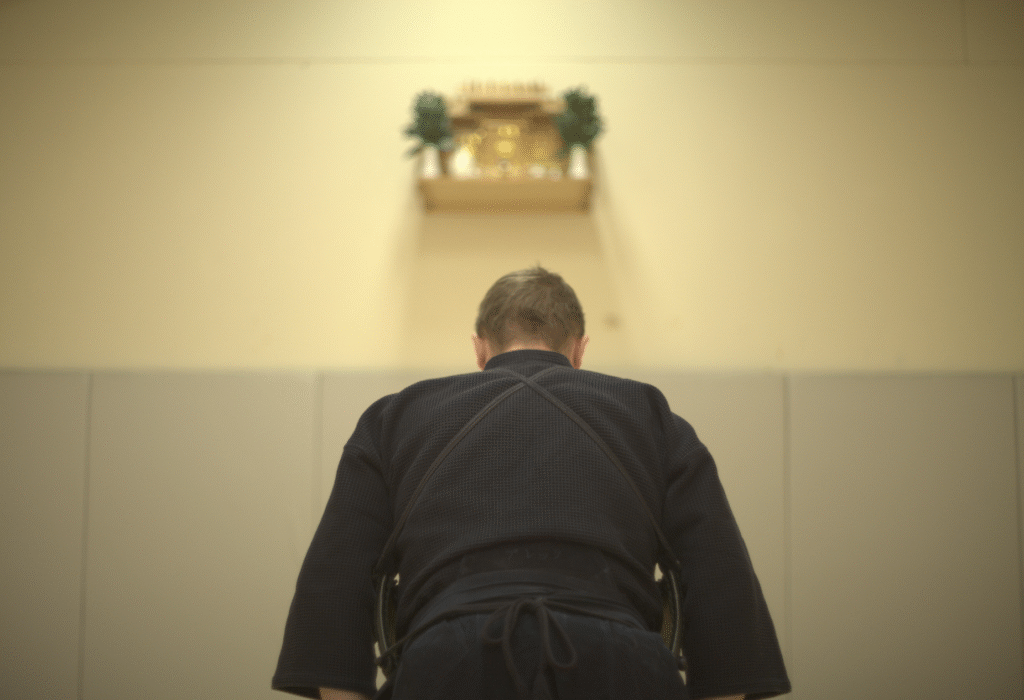

Moreover, a dan grade is not, contrary to cinematic and popular misconceptions, “a licence to kill”, nor even an automatic guarantee of unbeatable skill. Rather, it is meant to signify dedication, maturity, and resilience; it shows a willingness to engage with one’s vulnerabilities and strive beyond them. The most profound aspect of dan is less about meeting arbitrary external standards than it is about surpassing one’s previous self. At least, that’s the ideal.

At the moment, I find myself waist-deep in the Sisyphean odyssey that is chasing an 8th dan in kendo—a bold pursuit both humbling and absurdly ambitious. Just the other day, I found myself spectating at the 8th Dan Kendo Tournament, experiencing that curious blend of awe and mild despair as I watched Japan’s kendo elite move with seemingly effortless precision and subtle psychological cunning. It was a potent reminder of just how far I remain from the rarefied peaks they occupy. This infinite and perpetually elusive nature of the journey is precisely what makes the idea of dan quite compelling—it isn’t about finally having arrived, but continually setting out afresh, forever chasing a finer grasp of both competence and oneself.

This theme of dan and personal growth over mere technical prowess was brought home to me yesterday in an unexpected and inspiring manner. I received a message from Sweden regarding a young lad with Down syndrome whom I’d met on a previous visit in February this year. At the time, I taught him his first Iaido kata, though retaining new information was challenging for him. To my delight, his teacher informed me that recently he’d begun to recall and perform this kata with remarkable enthusiasm. Now, they are preparing to include this kata as part of his upcoming Shodan grading through the Association of Budo Culture for the Disabled (ABCD). Hearing this filled me with joy—not merely due to his accomplishments to date, but because this encapsulates the true essence of dan: focusing on what one can achieve, irrespective of external limitations or standards.

Dan, then, serves not as a “badge of honour” per se, but as a marker on an endless road towards deeper understanding and skill. Each rank attained represents hours of practice, introspection, and the quiet resilience to persist despite setbacks. Everybody’s journey is different. Everybody’s skill level is different. Everybody’s motivations are different. Indeed, the only universally shared aspect of the journey is that no one quite knows where they’re headed, but they’re heading there all the same.

However, the unfortunate reality is that budo, like many spheres of human endeavour, isn’t immune to snobbery or criticism from self-appointed gatekeepers. There are those curious characters who, upon achieving some lofty (or, not-so-lofty) dan rank, suddenly ascend into a celestial state of self-regard. Overnight, they metamorphose from humble practitioners into insufferable demigods, dispensing wisdom nobody asked for and commands nobody wishes to obey. It’s as though they believe attaining high dan automatically confers upon them divine right to lord it over the mere mortals who still stumble about on earth. Watching them strut is entertaining at first, until you realise you’re witnessing the martial arts equivalent of someone crowned King of the World simply because they found a throne unoccupied.

Then there are the keyboard warriors, ever quick to judge and disparage. These self-appointed guardians of martial purity wage their fiercest battles exclusively with a “caps lock”, comfortably shielded by anonymity. They gleefully fat-shame practitioners whose physiques fail to align with their cinematic fantasies, or non-lethality-shame martial artists whose techniques wouldn’t instantly dispatch an assailants in a ‘real’ fight. They show astonishing inventiveness in their relentless quest to critique every detail. “Huh! A BLACK BELT shouldn’t be like that!” they lament. “Must be more BULLSHIDO!”

All this righteous indignation is supposedly justified because martial arts must always be… well, exactly how they see it. Such critics fail to grasp a crucial point: a dan or black belt means vastly different things across various disciplines, and for different people, at different stages in their lives. And, frankly, it’s none of their bloody business anyway, is it?

Criteria for dan in kendo, for example, differ markedly from the same ranks in judo, reflecting each discipline’s distinct philosophies and practices. Even within karate, different styles maintain their own criteria shaped by tradition and lineage. Some schools or styles make it easier than others to pass examinations. Some federations emphasise technical excellence in dan examinations right to the end, while others also reward significant personal contributions in promoting and preserving their art. I think that such differences are not flaws, but a testament to the richness and adaptability that make budo arts endlessly fascinating to so many people from all walks of life.

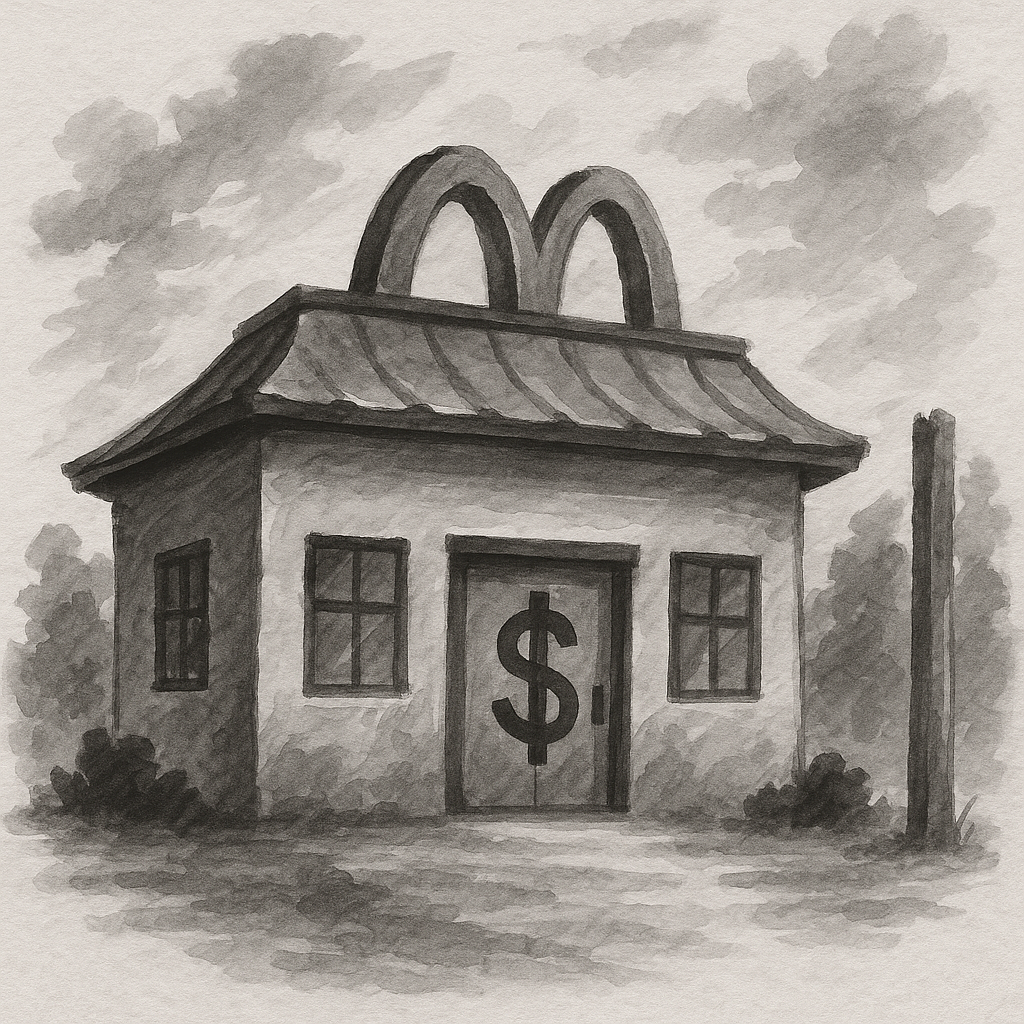

There are, of course, the notorious “pay me cash and I’ll give you a black belt” establishments, often derisively termed “McDojos.” Most people don’t realise, however, that these McDojos have existed in Japan for centuries; samurai and townsmen regularly exchanged envelopes of cash with dojo proprietors for titles and ranks. This is nothing new. But, to be brutally frank, why should anybody give a damn about such trivialities? There is no universally definitive dan rank. If some people wish to create their own, good luck to them, I say. If they want to buy a blackbelt, well so be it.

My focus remains singularly on my own personal improvement in the budo disciplines I choose to study. And to me, dan examinations serve to keep me honest, motivated, and humble. It’s my path—what others do on theirs is none of my concern (unless they ask for my opinion). Many people don’t even care about taking dan examinations. They just enjoy training and/or competing. And good luck to them as well! I know many. They would argue that budo is NOT about attaining dan grades. I don’t disagree, but they DO have their place in the culture of modern budo.

I think in the final analysis that Kanō Jigorō’s innovation was quite brilliant. The dan ranking system in budo is invaluable for clearly marking a student’s progression, motivating consistent improvement and personal growth. It establishes structured goals and milestones, guiding practitioners steadily from fundamental techniques to advanced mastery. By providing standardised benchmarks, the system ensures uniform evaluation within a discipline across diverse dojo, schools, and regions, and federations. It enhances safety and responsibility, ensuring students develop foundational skills thoroughly before attempting higher-level techniques. Dan ranks foster humility and ongoing learning, as achieving a given dan signals the real start of deeper understanding rather than a final achievement. The hierarchy generally promotes mutual respect among practitioners, clearly distinguishing roles and responsibilities within the dojo. Ultimately, the dan system preserves the integrity of the martial art, safeguarding traditions, and ensuring authentic transmission to future generations.

Sadly though, I know quite a few people who give up budo altogether after failing some dan examination a few times. This attitude is disappointing, as it entirely misses the point. These individuals allow pride and external validation to overshadow the genuine purpose of their practice. Dan grades are merely guideposts along the journey, not ultimate destinations. When practitioners lose sight of this fact, they risk turning away from invaluable personal growth and deeper understanding. Just because you take an exam doesn’t mean you’ll pass. I would have thought that was a given. If this is not acceptable, I guess there are plenty of McDojos where you can go and buy a certificate to hang on the wall…

Ultimately, the dan system isn’t just about rank—it’s about shaping character, preserving authenticity, and inspiring lifelong growth in the fascinating pursuit of budo. In a world often caught up in superficial standards and digital gatekeeping, perhaps the most meaningful aspect of dan is simply this—it is an indication of what we can become, rather than what we already are.

That said, I still want to pass that exam on May 2 in Kyoto! Ganbarimasu~

No comments yet.