Budo Beat 40: Kitamoto – Fifty Years, Countless Faces, One Spirit

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The “50th International Kendo Leaders’ Seminar” has just finished in Katsuura’s Nippon Budokan Kenshuu Centre. It’s hard to believe that this event has been shaping kendoka from around the world for half a century now. The first seminar was held at the Nippon Budokan Kenshuu Centre in 1975. From the following year, 1976, it moved to Kitamoto (Gedatsukai) in Saitama, where it stayed for decades, long enough for “Kitamoto Camp” to become etched into the DNA of international kendo.

Then came the pandemic, and everything stopped dead. When the seminar finally resumed in 2022, Kitamoto’s legendary sardine-style sleeping quarters (ten bodies to a room, minimum) suddenly looked less like character building and more like a public health hazard. Kitamoto is an absolutely fantastic facility all the same. The dojo is phenomenal, and the Gedatsukai people wonderful. Nevetheless, the whole thing went full circle back to its birthplace in Katsuura. The Kenshuu Centre, perched above the Pacific, now offers private rooms, perfect for socially distanced soul searching. Technically, it’s no longer the “Kitamoto Camp”, but good luck convincing anyone to call it anything else. The name is soaked in too much sweat, laughter, and mutual suffering to wash off easily. I suspect it’ll stay in Katsuura for the foreseeable future, but KITAMOTO will prevail, at least in name.

In the early years, the seminar ran for a gruelling two weeks! Two solid, hard-arse weeks of kendo and communal living. The programme also included a day of instruction in iaido, a rare reprieve from the frenetic thrashing and bashing of kendo. There was even a mid-seminar bus trip to Nikko to help participants remember what sitting down felt like. By the end, everyone was battered, bruised, and looked like extras from a zombie film, glazed eyes fixed in the classic 1000-yard stare.

These days, however, the seminar runs for one week. Shorter for sure, but still intense enough to leave your legs trembling and your hands and feet raw. Traditionally, the seminar was held in late July and early August, the most BRUTAL stretch of Japan’s summer. The heat really was merciless, but that was part of the lesson. If it didn’t kill you, it made you stronger kind of thing. Kitamoto in summer was not for the faint-hearted!

After COVID, however, sanity prevailed. The seminar was shifted to March, when the weather is mercifully mild. This year, though, is a special one. It was held twice due to fiscal year budgetary considerations: once in March and again in October. Next year, Tokyo will host the first Asia-Oceania Kendo Tournament, and the year after that, the World Kendo Championships. With those major events on the horizon, the seminar will take a two-year hiatus. Thus, this October session was both a celebration and a farewell for a couple of years.

Back in the day, the seminar was kendo’s version of bootcamp. It was really tough, and participants wore the experience as a badge of honour. The seminar is now, by comparison, less demanding physically, but it is still intense. It consists of three full training sessions a day. Morning keiko starts at 6:30, focusing on fundamentals and building up rhythm and spirit. After breakfast, the 9:00 session begins with Nihon Kendo Kata, then technique practice in full armour. After lunch, the afternoon session covers refereeing and shiai, followed by more technical training and, finally, sparring with the sensei. After dinner, we would often be ushered into the centre’s classroom for a lecture on some aspect of kendo.

By the end of each day, most participants are physically spent and spiritually charged. Oh! Then, there’s the absolutey optional “free training” that starts at 6:00am which, in reality, kind of isn’t really optional…

As it has always done, the All-Japan Kendo Federation appoints a team of top-level 8th Dan sensei each year, so the quality of instruction is exceptional. Every movement, every correction carries a lifetime of accumulated knowledge. Attending this seminar is a real privilege, and it’s very difficult to get a place here. Each national federation may nominate several candidates, but the final selection is made by the AJKF. In recent years, only one person per country managed to get a spot. This time, the quota doubled to two, just like before COVID. A total of 56 participants from 38 countries joined in—a lively mix of men and women of all ages and temperaments.

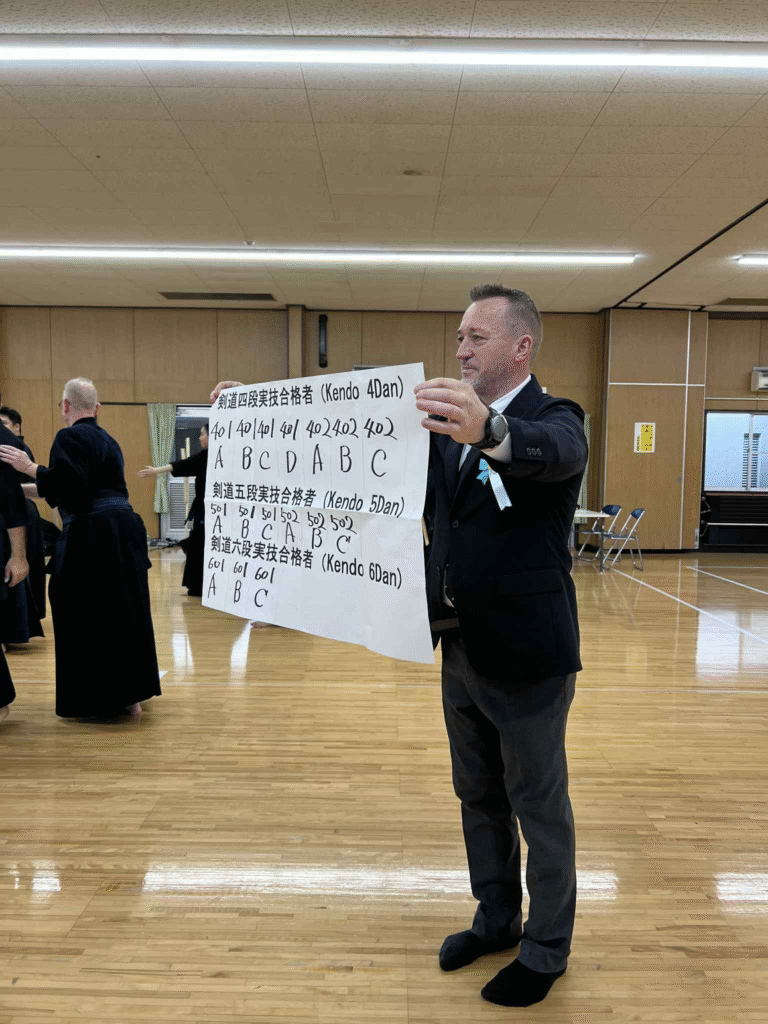

Applicants must hold at least 3-dan, as the seminar now focuses on those already in teaching roles within their home countries. In earlier times, beginners were allowed to attend, and on the final day examinations were held from shodan upwards. These days, the final grading is limited to 4-dan, 5-dan, and 6-dan. To ensure fairness, a completely separate panel of examiners is brought in. That is, senseis who have not taught during the week in order to prevent any bias. Watching friends succeed in those final-day tests is one of the most rewarding moments of the week. Seeing others fall short is equally painful. The joy and disappointment in that hall are unforgettable reminders of how deep the bonds become.

In the old days, the final night was reserved for the infamous Sayonara parties. Every room had to come up with some kind of performance. Considerable quantities of liquid courage were consumed, and the tales from those nights are still whispered with equal parts laughter and shame. What happens on tour stays on tour, so I’ll spare you the details of the many performances that veered somewhere between gut-splittingly funny and traumatically unforgettable.

Since the move back to Katsuura, and particularly after COVID, things have quieted down a lot. The evenings now feature formal lectures on topics such as anti-doping, the current situation of the International Kendo Federation, and the responsibilities of leaders in international kendo. Maybe it’s just as well. But those old Sayonara parties were unforgettable.

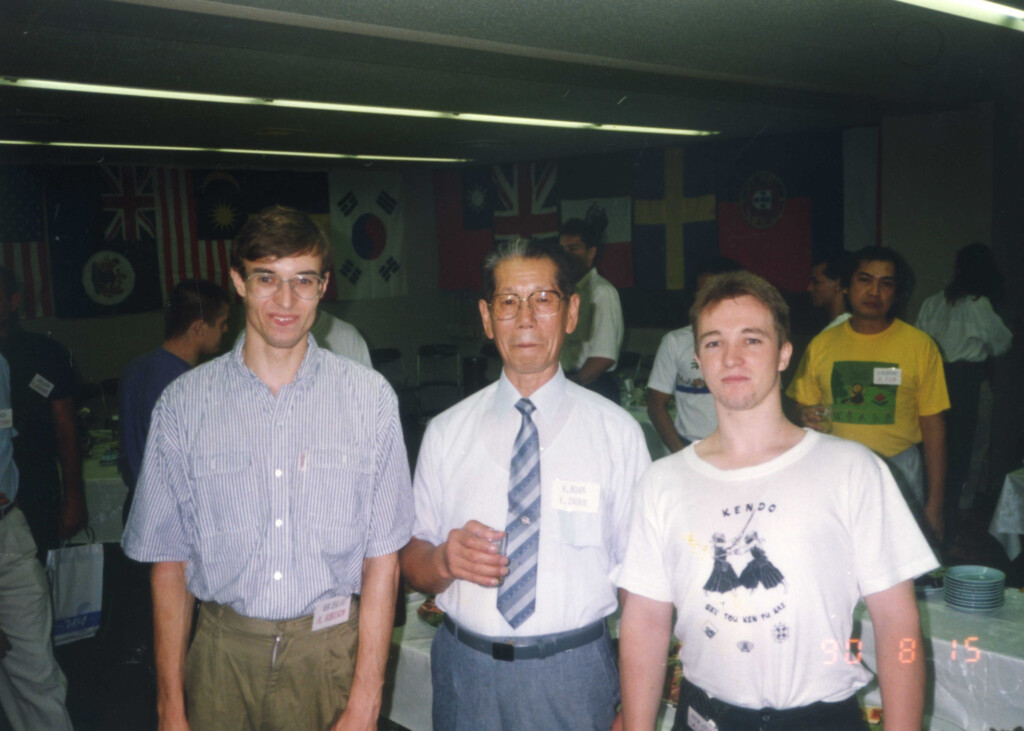

I first attended the seminar in 1989 as a participant. I was young, enthusiastic, and blissfully unaware of what I was getting into. The heat in the dojo was unbearable, the keiko endless, and the sensei were quite intimidating. I loved every minute of it. I made friends who have remained close ever since, and I learned that kendo was not just a martial art, it is a global community.

After a couple of times as a participant, in 1995 I was asked to serve as the interpreter for the seminar. I thought it would be a one-time favour. Thirty years later, I’m still doing it. Every year, I stand between Japan’s most senior instructors and the international participants, trying to convey not only the words, but the spirit of what’s being taught.

It’s one of the hardest jobs imaginable. Some sensei speak clearly and slowly, pausing every few sentences to let me interpret. Others seem to forget that an interpreter exists and talk for five straight minutes before stopping for air. Over the years, I’ve learned to adapt to every style, juggling nuance and timing while trying to stay true to the essence of what’s being said. I do add a bit of humour when appropriate as well, just to keep people on their toes. Sometimes sensei wonder what they said that people found so amusing.

We have a small team of interpreters who take turns because it is quite draining. This seminar fell at an awkward time, so I ended up doing most of the interpreting myself this time while the others were tied up with work commitments. Still, I suspect my days as interpreter are numbered. It’s only a matter of time before participants arrive with “smart contact lenses” that display live AI-generated subtitles of what the sensei are saying. When that day comes, I’ll probably be biffed away like a broken shinai. Truth be told, I’ll probably miss the chaos, the challenge, and the occasional miracle of getting a long, esoteric explanation of kendo philosophy across perfectly intact. For the meantime though, I’ll just keep enjoying it while I can…

Over the years, I’ve had the privilege of working with some of the greatest sensei kendo has ever produced. I’ve seen beginners grow into high-ranking leaders, and work hard for the dissemination of kendo in all four corners of the globe. I’ve watched the seminar evolve in content and mission, but its heart has never changed. You live, eat, and train together. You share exhaustion, bruises, and laughter. You learn that beyond rank, language, or nationality, everyone is here for the same reason. To polish themselves through the sword.

The Kitamoto seminar has produced generations of instructors who have gone home and built the foundations of kendo in their countries. I think it has been one of the quiet engines of international budo, quietly uniting people through practice and spirit. The friendships made here have outlasted politics, pandemics, and distance.

As for me, I’ve probably been to more of these seminars than anyone else with over thirty now. This event has been a constant thread in my life. Every year, the faces change, but the energy remains the same. At every international kendo event I go to, whether it’s the World Kendo Championships or something else, scores of people come up to me with a big grin and say, “Hi! Do you remember me from Kitamoto?” I always remember the faces, but after so many years the seminars have blurred together into one giant, sweaty memory, so I never remember which year it was.

Over the years, I’ve also been collecting materials, photographs, and documents from each seminar: participant lists, lecture notes, booklets, and memories that together form a living history of international kendo. One day, I’d like to compile it all into a book. The International Kendo Leaders’ Seminar deserves to be properly documented and celebrated for the vital role it has played in spreading kendo around the world.

This fiftieth anniversary feels special although it was hardly mentioned at all throughout the week. Fifty years of people from around the planet gathering to train, learn, and connect. From my estimation, nearly 3000 kenshi have come to the seminar over the years and carried a small piece of Japan home in their hearts. That’s the real legacy of the camp. Standing there again as interpreter, surrounded by old friends and new faces, I feel both continuity and change. Kitamoto Camp, wherever it’s held, is more than a seminar. It’s a living bridge between cultures, a forge of friendship, and a reminder that the true essence of kendo is not just in seeking the secret to perfect strikes, but in the spirit we share when we bow, shout, and persevere together. Fifty years on, that spirit is alive and well in Katsuura!

No comments yet.