Budo Beat 41: Samurai Journey in Sakura

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

The Kitamoto Camp ended on a Friday afternoon. Everyone was running on the faint fumes of keiko, lectures, and too little sleep. The idea of setting off immediately on another kendo trip might have sounded insane, but that’s exactly what we did.

Three participants piled into the car with me, and we drove two hours northwest from Katsuura toward the old castle town of Sakura. This was the start of our new program, The Samurai Journey in Sakura, supported by Kendo World, Sakura City, and Narita Airport. The idea was to offer international kendo people a chance to experience a real slice of samurai Japan just an hour from Tokyo, and even closer to Narita Airport.

Sakura: The City of Quiet Power

Sakura, not the cherry blossom but 佐倉, meaning “warehouse of reeds”, sits on the Shimōsa Plateau, about 40 kilometres from Tokyo and fifteen from Narita Airport. It was once a major castle town of the Sakura Domain under the Tokugawa shogunate. During the Edo period it played a strategic role guarding the eastern approaches to Edo. Unlike other famous castles such as Himeji or Matsumoto, Sakura Castle had no stone walls. It relied instead on enormous earthen embankments and deep dry moats for defence, making it one of the more unusual fortifications in Japan, and a potential disaster for any drunken samurai who happened to stumble into those giant holes at night. The castle grounds are now a park, and the National Museum of Japanese History (Rekihaku) sits right in the centre where the keep once stood.

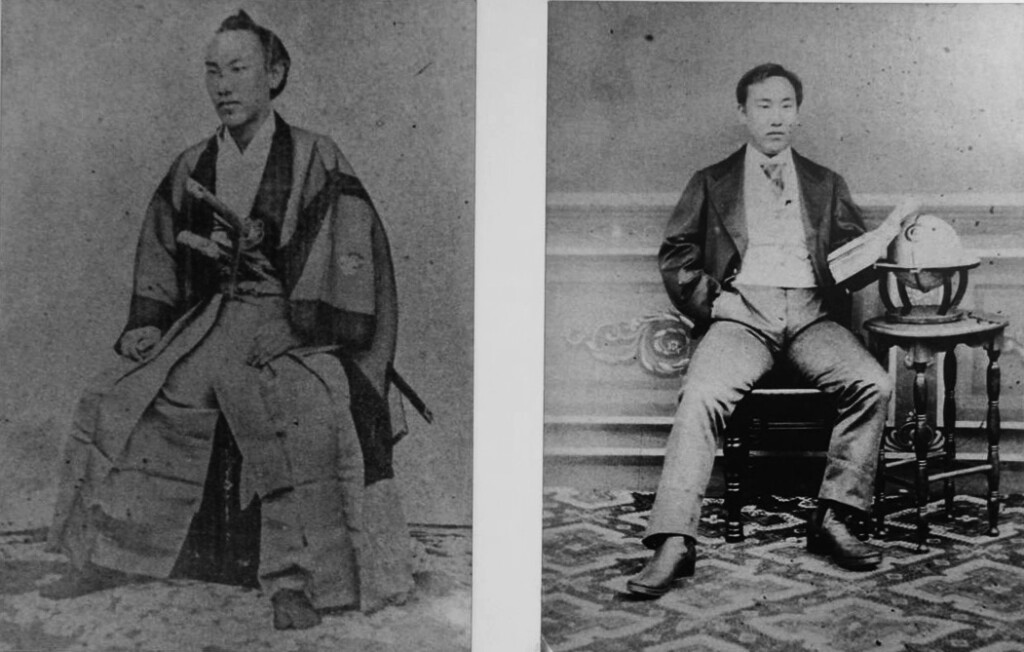

The domain’s ruling Hotta clan were among the more progressive of the Tokugawa period. They encouraged learning and diplomacy, and by the 1850s, Hotta Masayoshi was one of the most prominent reformers in Japan. He negotiated with Western envoys, supported the opening of Japan, and paid for it politically. Sakura’s story is therefore not one of provincial obscurity, but of a domain trying to navigate modernity while balancing loyalty and reform.

That mix of history and quiet dignity, I think, defines Sakura. The town doesn’t try to impress you. It invites you to listen.

Friday, October 24: The Hotta Residence and Zazen

Our first stop was the Former Hotta Residence, a beautiful Meiji-era compound constructed after the Meiji Restoration, around 1890, by Hotta Masatomo, the last lord of the Sakura Domain. It reflects the period’s shift, showing how the Hotta family adapted from feudal lords to modern nobles under the new state. The building and its gardens are now an Important Cultural Property, one of the finest examples of a high-ranking ex-samurai home that survived Japan’s rush to modernisation.

What makes it fascinating is its architectural duality. It’s both samurai-esque and modern Western gentleman. One moment you’re stepping across polished tatami into a quiet study with calligraphy scrolls, the next you’re looking up at an imported chandelier in a Western-style guest room. The shift mirrors Japan itself at the end of the nineteenth century.

We were allowed into the second floor, normally closed to the public. There, above the frighteningly steep staircase, we sat for zazen with a local Rinzai sect Zen priest. He didn’t speak English, but in an act of unexpected harmony between tradition and technology, he used ChatGPT on his phone to translate his instructions. The voice of the AI, coming cheerfully through the Bluetooth speaker, spoke with calm politeness and not quite perfect timing, as if it too were taking part in zazen. At one point, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘The end is nigh for me.’ The translation really was spot on. Soon I’ll be redundant, I thought, as the friendly American voice carried on translating, as if calmly accepting my own obsolescence. My knees creaked.

The garden outside glistened in afternoon light. It had its boundary, yet it felt boundless. The light had no source. The priest asked, “What is the sound of Wi‑Fi when there is no signal?” The phone replied, “Reconnecting.” The priest nodded. Enlightenment was buffering.

Well, that didn’t actually happen, but the silence was so complete it felt alive. Sitting in a samurai lord’s home, meditating under the guidance of a priest and an algorithm, we became a small experiment in continuity. Old Japan, new tools, same human search for awareness.

That evening, we changed gear and went to the Sakura City Gym for keiko. The local 7th dans came out to meet us, and it didn’t take long before everyone was sweating and smiling. There was no polite warming up. Just clean, committed kendo. The kind that erases language differences and jet lag in a single strike.

Saturday, 25 Oct.: Rekihaku, Kobudo, and the Domain Dojo

On Saturday morning, after overdosing on Nitro Coffee at the hotel, we were transported to the National Museum of Japanese History, known affectionately as Rekihaku. It’s one of Japan’s most comprehensive museums, covering the sweep of Japanese history from the Jōmon era to modern times. The site itself sits on the old Sakura Castle grounds.

We started in the medieval gallery, surrounded by vivid displays of life in that period, and wonderful reconstructions of samurai manors and townships. I gave the group a short talk to give some context, explaining how the samurai rose from Kyoto’s courtly aristocrats and provincial militias to become the country’s ruling class, and how that power eventually had to be softened with ethics, education, and restraint. After that, everyone explored freely. You could easily spend a week there. We had only a morning.

Rekihaku is astonishing. It doesn’t feel like a museum built to impress tourists. It feels like a long conversation with history. The museum is divided into large pavilions representing different eras in Japanese history—from the Jōmon and Yayoi through the medieval, Edo, and modern periods—covering both history and folk culture right up to the present day. One pavilion recreates a lively Edo street, another shows how the architecture of a samurai home reflected hierarchy and duty. Surprisingly, there were no dramatic displays of samurai weaponry as one might expect, because that is only one small part of the broader picture of Japanese culture presented here. We would see some magnificent blades the following day in the nearby Tsukamoto Sword Gallery.

In the early afternoon we gathered for a special lecture and demonstration on Tatsumi-ryū Heihō, one of Japan’s oldest surviving martial traditions, founded in the early 1500s by Tatsumi Sankyo in nearby Shimōsa Province. The school embodies the classical bujutsu curriculum of the Sengoku period, when martial systems had to address every aspect of combat, sword, spear, grappling, strategy, and mental readiness. What makes Tatsumi-ryū unique is its emphasis on comprehensive strategy: victory through awareness and adaptability rather than brute force.

The head instructor, Yamada-sensei, and his student demonstrated kata with sword, yari, short-swords, and unarmed techniques, explaining how these forms developed in the chaos of civil war and later became tools for moral training under the Tokugawa peace. Watching the paired forms performed with quiet precision just a short walk from the old castle grounds was like stepping into a time capsule. For the participants, it bridged the academic world of Rekihaku and the living practice of classical budo.

In the afternoon, the focus shifted back to modern budo. We held the first Kendo World Keiko-kai since the pandemic, at the old enbujō, the training hall that once belonged to the Sakura Domain’s academy for young samurai. The hall itself is a treasure. Alas, it now serves as a general gymnasium for all sorts of sports. I wish it were still reserved for budo, but such are the times we live in. Budo is slowly becoming a minority pursuit in Japan.

When keiko began, the air vibrated. Visiting 8th dans joined local teachers and international kenshi. Everyone gave everything. The sound of kiai filled the space, blending perfectly with the rhythm of history beneath our feet.

Afterwards, we relocated to the second dojo, otherwise known as the banquet lounge at the Wishton Hotel. It was a civilised affair, followed by a less civilised third dojo in the izakaya below the hotel…

Sunday: Samurai Houses and the Tsukamoto Sword Gallery

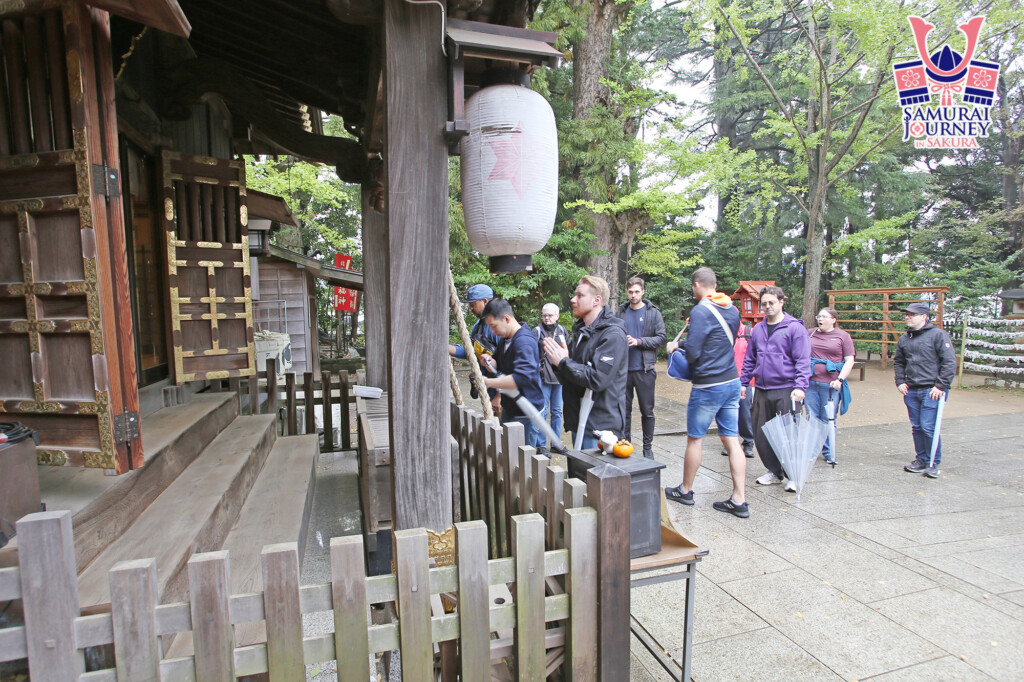

Even more Nitro Coffee. We then travelled to the old Bukeyashiki-dōri, the samurai quarter that once housed the retainers of the Hotta clan. Three homes, the Kawara, Tajima, and Takei residences, have been preserved exactly as they were in the late Edo period.

These were the homes of mid-ranking retainers, not lords. Their quiet simplicity speaks volumes about samurai life at the working level. The rooms are small and spare. A single scroll, a tokonoma, a sliding door that opens onto a garden, a dingy smokey kitchen… The sound of the wind brushing through bamboo. You can sense the rhythm of daily life, letters being written, armour being maintained, lessons being taught.

Sakura’s samurai district is one of the best preserved in the Kanto region. It’s remarkable that it survived at all. Walking through it feels like slipping out of the twenty-first century entirely.

From there, we made our way to the Tsukamoto Museum, also known as the Tsukamoto Sword Gallery. It houses the private collection of Tsukamoto Sōzan, a Sakura-born businessman who spent decades acquiring fine Japanese blades. The museum is small and quiet, and soft lighting reveals every detail of the steel.

The swords range from Kamakura-era masterpieces to Edo-period katana, each showing the evolution of craftsmanship. The hamon, the temper lines, shimmer like ripples on water. Standing in front of them, our group fell silent again. It was a different kind of meditation. The perfection of the blade speaks its own language.

Afterwards, we ducked into an old soba shop, where everyone ordered the same thing without even looking at the menu. Conversation trickled off, and soon it was just the sound of slurping and satisfied sighs. We shuffled outside, and disbanded in front of Sakura station, each of us drifting back into the mundane world.

Reflections on Sakura

Sakura has more layers than most people realise. It was not only a military domain but also a centre of scholarship and reform. It has one of Japan’s few remaining samurai neighbourhoods, a major national museum, and even a Dutch windmill by Lake Inba called De Liefde, “The Love,” built in 1994 as a symbol of cultural exchange. The name recalls the Dutch ship that first brought Western books to Japan in 1600.

And it’s older still. Archaeologists have found Jōmon-period settlements nearby, including the Inonagawari Site, which dates back more than 3,000 years. Long before the Hotta clan built their castle, people were already shaping and reshaping the land. That continuity is what makes Sakura so fascinating. It is not a city of monuments. It is a city of quiet persistence.

The Samurai Journey in Sakura will return next year, and there is still a lot left to see. Still, even if we repeated the same route, it would be different, because people change, and so does the way we see. I’m really looking forward to round 2! Come join us!!

As I drove back toward Kyoto, the Sakura faded in the rearview mirror, replaced by rice fields and open sky. I thought of something the Zen priest said before our meditation: “When you know stillness, you can see movement clearly.”

No comments yet.