Budo Beat 53: Chōtan Ichimi – The Long and the Short of Jukendo and Tankendo

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

Over the weekend I sat the 7th Dan examinations for both tankendo and jukendo. It was a pretty tough weekend that left me physically wrung out and somewhat unsettled, but in a good way. Examinations have a habit of doing that which is why most sane people don’t do two high level examinations in tandem. You think you’re all relaxed, heijōshin’d out, but then the mind starts the old “but what if…” game. Times 2!

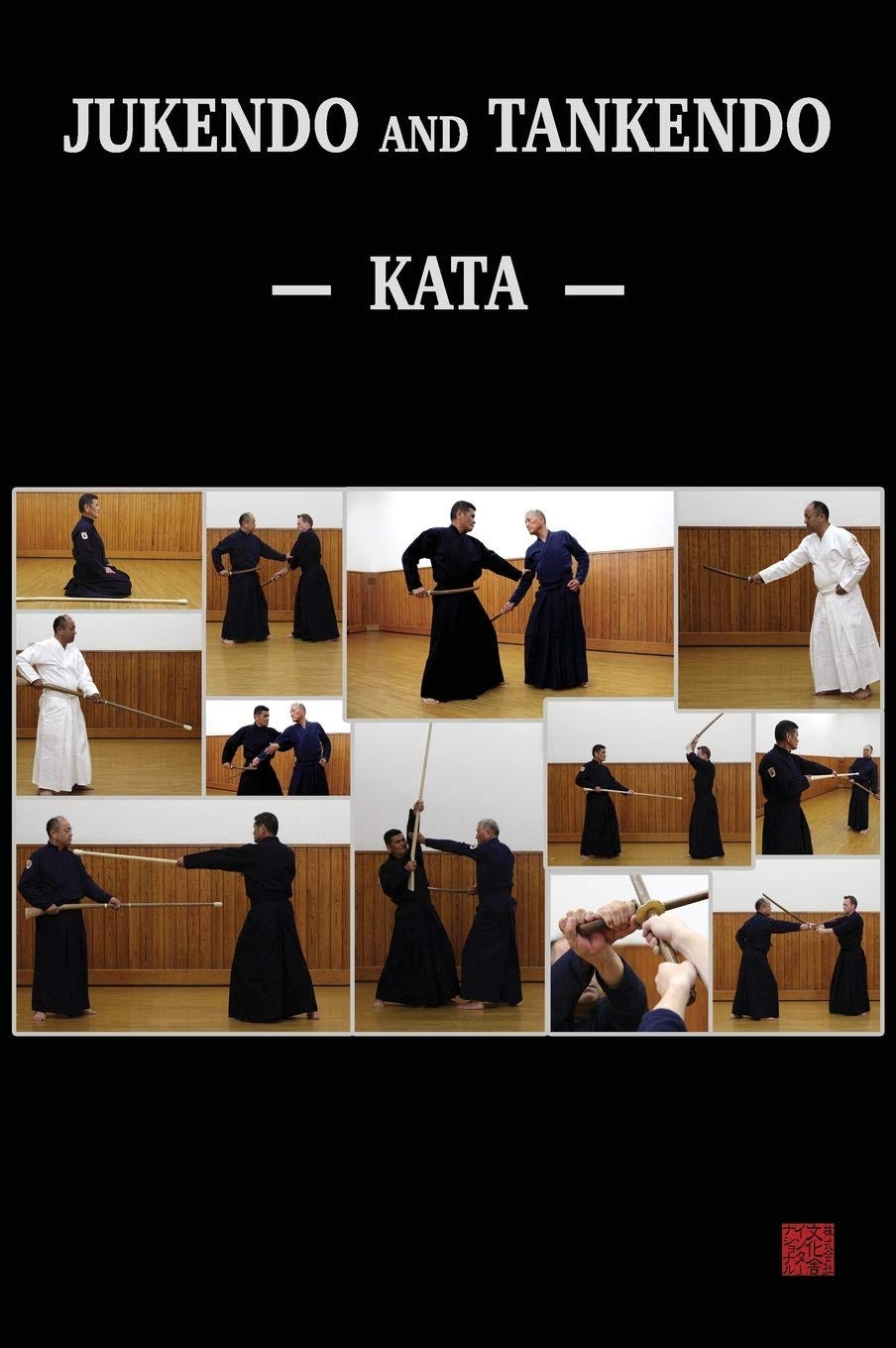

For those who don’t know, jukendo is the Japanese martial art of bayonet fencing. Practitioners use a mokujū, a wooden rifle with a simulated bayonet and a big rubber safety cap, and engage in kata and matches that revolve almost entirely around thrusting. Historically, jukendo took shape in the Meiji period (late 19th century), when Japan was absorbing Western military systems at a remarkable pace. Even Tom Cruise was right there in the thick of it.

Bayonet training was imported from Europe as part of the modernisation of the armed forces, yet it did not arrive in a cultural vacuum. The Japanese already had centuries of experience with thrusting weapons through sōjutsu, the classical arts of the spear. Jukendo, as it developed, became a distinctly Japanese hybrid. Western bayonet mechanics were filtered through indigenous ideas about maai, posture, spirit, and decisive entry (irimi).

Tankendo (the Way of the short sword) sits under the broader umbrella of jukendo in much the same way that iaido and jodo sit under the All Japan Kendo Federation. Tankendo is not a dagger art per se. The weapon is an unaffixed bayonet or short sword (tanken). The length, weight, and balance place it somewhere between knife work and sword work, demanding its own solutions rather than borrowed assumptions.

Tankendo and jukendo kata come in many combinations. Mokujū versus mokujū. Tachi (sword) versus mokujū. Tanken versus mokujū. Tanken versus tachi. Tanken versus tanken. Did I get them all? Each pairing forces you to recalibrate your sense of distance from scratch. You cannot coast on habit. The maai that keeps you safe but ready to strike in one exchange will get you well-and-truly skewered in another. This constant recalibration is exhausting, but it is also very educational.

What jukendo and tankendo demand above all else is commitment. Hesitation is not interpreted as thoughtful restraint. It is interpreted, quite correctly, as an invitation. You must enter. Again and again. Half measures do not survive contact with a thrusting weapon. This is where irimi (入り身) stops being a theoretical concept and becomes an embodied necessity. Irimi literally means “entering the body”. It is not simply stepping forward, but committing your whole body and intent into the opponent’s space, using the body to seize distance rather than relying on the reach of the weapon or hovering at its edge. If you hesitate, if you try to negotiate distance rather than seize it, the point finds you.

From the outside, jukendo and tankendo often look unsophisticated. This is usually said by people who have never stood in front of a committed thrust and suddenly found religion! A lot of forward pressure and direct thrusting, but not much visual variety. That impression, however, rarely survives first-hand experience. The apparent simplicity strips away decorative movement and leaves only essentials. Timing. Distance. Angle. Spirit. Whammo. The margin for error really is brutally small. Being a few centimetres off is the difference between dominance, and disgrace with a mokujū inserted firmly where the sun doesn’t shine. This is very close to a teaching you hear constantly in kendo: find the distance that feels close for you, but far for your opponent.

This brings me to the idea of chōtan ichimi (長短一味), “long and short as one and the same”. At the risk of stating the obvious, and resisting the temptation to smirk, this is one of those lessons that really is not about length at all, but about how you use it.

Classical martial teachings return to this theme repeatedly. I think I’ve covered this in another blog post somewhere as well. In any case, victory is not determined by the length of the weapon, yet length cannot be ignored. The tension between those two statements is deliberate. It’s meant to disrupt simplistic thinking. One verse traditionally attributed to the famous swordsman Tsukahara Bokuden captures this balance rather succinctly. It appears after a discussion of reach and commitment, and serves as a warning against both overconfidence in length and attachment to shortness:

Victory in a contest is not decided by whether the blade is long or short—yet do not grow fond of an excessively short blade.[1]

This verse is not arguing that long weapons are inherently superior, nor that short ones are inferior. Its first line makes that clear: victory itself is not mechanically decided by length. Skill, timing, distance, intent, and judgement matter more than simple measurements. The warning comes in the second line. “Do not grow fond of an excessively short blade” is a caution against turning a limitation into a preference. A very short sword may feel lighter, quicker, and easier to control, especially at close range, but that comfort can be deceptive. Habitually relying on a short blade narrows one’s sense of maai (distance), encourages entering too close, and reduces the margin for error against an opponent who controls space well.

In classical kenjutsu terms, this is less about equipment than mindset. Becoming attached to a particular length reflects attachment to ease and familiarity. The point is not that weapons don’t matter. It’s that weapons only matter in relation to the person wielding them, the opponent facing them, and the space in which they meet. Jukendo and tankendo makes this very clear.

A second verse by the Edo period swordsman, Fujikawa Chikayoshi (1727-1798), pushes the idea further, shifting the focus away from equipment altogether and onto judgement itself:

Why argue over long and short? Cut the opponent with the sharp blade of the mind.[2]

As always, this is easy to quote and hard to live. In practice, it demands judgement under pressure. In tankendo, especially, the temptation is to fixate on what you lack. The weapon feels short. The opponent feels too far away. The mind starts bargaining. That is precisely when you are required to let go of measurement and commit fully to entry.

Because tankendo and jukendo cycle through so many weapon pairings, they teach something that many budo only gesture toward: distance is not a constant. It is relational. When facing mokujū with tanken, retreat is not a viable strategy. Neither is waiting. You must live inside the opponent’s effective range and make a decision. Conversely, when holding the longer weapon, you learn very quickly that length is useless without resolve. If you lack resolve, the extra length does nothing for you. Without intent behind it, a long weapon stops being an advantage at all.

This is where the Meiji-period hybridity of jukendo becomes especially interesting. Western bayonet systems proritised assertive forward pressure and linear advance. When absorbed into Japanese budo culture, that emphasis was reframed through older sōjutsu sensibilities, where distance was never a matter of reach alone. Classical spear work understood that maai is claimed with the body, not the arms. That logic persists in jukendo today: effective extension comes from stepping in with structure, not stretching out with the hands. It also explains why jukendo looks relentless. Once committed, there is no room for hesitation. You either occupy the space or you lose it.

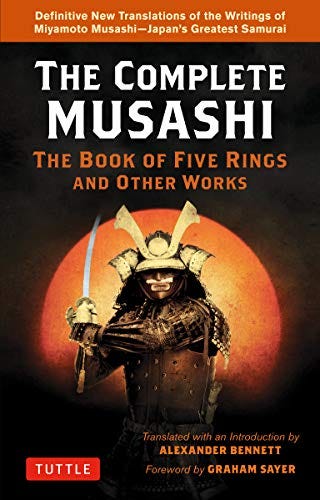

Of course, Musashi had something to say about this, too. In the Water Scroll, he states,

The ‘Body of an Autumn Monkey’ refers to a procedure in which you do not extend your arms. Encroach into the enemy’s space whilst keeping your arms tucked in. Focus on getting as close as possible before executing the strike. Your torso will lag behind if you simply reach out, so try to move your whole body in close as fast as you can, with your hands tucked into your body. It is easy to pounce when you are at arm’s length. Study this well.

Standing on the floor over the weekend, moving repeatedly between these different ranges, I was struck again by how misleading the language of advantage can be.

The timing of all this was not lost on me. The day before the jukendo and tankendo examination, I had demonstrated Hōjō no Kata with a junior from my university iaido club days at a small gathering at Chiba University. We had not trained together in years. Yet there we were, working through a kata whose fourth sequence bears the name chōtan ichimi, the very principle I would spend the next few days grappling with under far less forgiving conditions. Theory has a way of sounding neat until practice intervenes. Every confident theory about reach and safety has a habit of evaporating the moment someone decides to step in properly and try to cosh you.

At this point, it is hard not to hear Musashi in the background. In the Gorin no Sho, he makes essentially the same argument, only more bluntly: if you become attached to the length of the weapon, long or short, you have already lost the freedom to adapt.

The idea surfaces explicitly in classical kata. It is no accident that the fourth kata of Hōjō no Kata in Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryū is also called Chōtan Ichimi. The kata is taught early in the school precisely so that the practitioner learns to feel this balance before worrying about victory or defeat. Long and short become one only when judgement is sound. Without that, neither will save you. (You can read about this in one of my previous blogposts here.)

That, perhaps, is why jukendo and tankendo continue to attract a small but stubborn group of practitioners outside the Japanese SDF. They are certainly not glamorous (these budo arts, I mean), and they don’t offer endless variation. What they offer instead is pure and simple honesty. Hesitation is noticed at once, and any woolly thinking is dealt with pretty goddam quickly and mercilessly. Commitment, on the other hand, is met in kind, and it is absolutely exhilarating.

After the examinations, tired and slightly relieved, I found myself thinking about why I keep returning to these “less fashionable” corners of budo. They strip things back and remove comforting illusions. They remind me that budo is not so much about collecting techniques or debating specifications, although there is a place for this in the learning process. It’s more about choosing correctly under pressure and accepting responsibility for that choice in an instant, with what you have in your hands (or not, as the case may be).

Long or short. Bayonet or short sword. In the end, the logic is the same. What matters is whether you can read distance, commit without flinching, and step into the space that decides almost everything.

Oh, and I just found out I passed both exams. Yippee.

[1] Shōbu wa nagaki mijikaki kawaranedo / sanomi mijikaki tachi wa konomiso, Imamura Yoshio et al. (eds.), Kindai Kendō Meicho Taikei, vol. 10, Dōhōsha Shuppan, 1986 p. 156

[2] Chōtan o ronzuru kokoro aran ya / hito o kokoro no riken nite kire, Yamada Jirōkichi, Kendō Gokuigi Gikai, Suishinsha, 1937 p. 66

No comments yet.