Budo Beat 3: “Bu’un Happens” – Reflections on the 72nd All-Japan Kendo Championships

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a random collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way. Feel free to leave comments at the bottom.

Today, I had the pleasure of attending the 72nd All-Japan Kendo Championships at the Nippon Budokan. This year was a bit special, as both the men’s and women’s competitions were held simultaneously, and the atmosphere was electric—the venue was packed, buzzing with energy.

I was especially invested in one competitor, Goya Ryo, representing Kyoto Prefecture—my home of over thirty years. I was also cheering for a former student from Kansai University competing for Nara, and a woman competitor representing Kanagawa whom I’d recently had the pleasure of getting to know at the BKA 2024 international seminar in England. Each of them put in magnificent performances, and I couldn’t help but feel a little proud to know these supreme athletes.

But back to Goya. Long story short, he fought his way to the finals, showing incredible skill and heart in every match. Then came the final—a showdown that was both swift, intense, and worthy of the conclusive bout of the day. (As was the women’s final! Video here.)

I was there for “Kendo World”, not just as a Kyoto supporter, snapping thousands of photos throughout the day. I’ll be honest, I didn’t get as many good shots as I’d hoped, but I did manage to capture one gem: the exact moment of that final men strike. (See image above ↑)

Kendo uses a “best of three” system, where the first competitor to score two points wins. Takenouchi Yuya’s first kote strike was a thing of beauty, resonating through the Budokan like a Taiko drum—no room for doubt there. Then, Goya lost to a men strike—a decisive second hit that ended the bout. Goya was defeated, but it was another fantastic win for Takenouchi Yuya, a seasoned champion and true kendo icon.

But as I looked at my photo of the final men strike, it seemed a little… off. Was Goya’s loss undeserved? The freeze-frame made it look like the Shinpan might have missed something. But hold on! I’m certainly not about to jump on the “blame the refs” train.

And, speaking of trains, on the Bullet Train back to Kyoto that night, I shared the photo with my sensei, who also just happens to be Goya’s teacher in the Kyoto Police. His response was classic: “Yeah mate, it’s Bu’un.” (Not exactly in NZ English, but you get the idea.)

In hindsight, sure, the men strike wasn’t actually on the target. But, as my sensei reminded me, “Bu’un, it is what it is.” In kendo, split-second decisions decide the outcome, and there’s always an element of momentum and luck that leads to that point. The real trick is figuring out how to tip that luck in your favour. And if not, accepting that it just wasn’t your day, as impetus was with the other competitor, for whatever reason. So, what do you do about it? “You bloody well deal with it, and get back to training.”

“Bu’un” (武運) is a term that non-Japanese martial artists might not know, but the concept is surely recognisable. It translates to “martial luck” or “the fortune of battle” and acknowledges that skill alone doesn’t decide outcomes. Forces beyond our control shape events, reminding us that no matter how prepared we are, some things are just determined by chance.

Bu’un reminds practitioners that victory and defeat aren’t solely determined by individual actions; they’re shaped by forces that no one can fully anticipate or command. You do your best to prepare for the big day, to control as much of the outcome as you can, but there is always an element left in the lap of the gods, so to speak.

This idea is integral budo, and teaches humility, resilience, and acceptance of outcomes. All you can do is prepare as perfectly as you can, and then put everything on the line. Bu’un essentially dictates the outcome. Alas, it doesn’t always go your way, but you just have to deal with the cards you’re dealt. We’ve all won matches we perhaps thought we shouldn’t have, and lost matches we thought we should have won. It’s just a fact of life, and life isn’t always fair. Who can say why this happens? It’s funny how we usually dwell on the latter…

As such, you can resign yourself to being seriously pissed off with how inequitable everything is, or you can accept the outcome and move on. Let’s put a positive spin on it. Whether in kendo, other budo, sports, or even life itself, Bu’un reminds me of the beauty in the unpredictable, and the necessity of embracing the “flow of things” with respect and grace. Easier said than done, but an ideal worth aspiring to!

Incidentally, a few hours before the 72nd All-Japan Kendo Championships, the All Blacks narrowly defeated England 24-22 in a rugby test match in Twickenham. If the English kicker had slotted two glorious opportunities to send the pill flying between the posts in the dying minutes of the game, England would have won. But, for some reason, what would be usually routine kicks for these professionals went horribly astray, and England lost to the NZ All Blacks (again 😉). Yay for us Kiwis! But why? How? What went wrong? I bet the English kicker couldn’t tell you. It was Bu’un. The momentum swings to one side, and victory is decided. Bu’un happens. Not exactly budo, but the principle is the same.

Back to the kendo championships. Kendo is not only a competitive sport; it’s a budo discipline rooted in resilience, respect, and acceptance of outcomes, even when they seem unfair. Today’s experience was really a reminder to me of these principles. Sometimes we lose, not because of a failure in skill or a lack of spirit, but because of something intangible—a twist of Bu’un. I don’t think the Shinpan were bad in any way. As always, they were the best of the best, doing their best; and they made their call based on what they saw, heard, felt, smelled in that instant. I too, absolutely thought it was ippon until I looked at the photo I took.

There’s a lot of “Shinpan bashing” online these days, and I don’t subscribe to that at all. It’s easy to criticize when you’re watching, not doing. I’m also not in favour of using video reviews or other technology to “confirm” these moments—how often does the TMO get things wrong in rugby! I’ll save my thoughts on these irksome issues in budo for another time.

To me, the beauty of kendo lies in the simplicity and humanity of its process, flawed though it sometimes may be. Each strike, each decision, exists purely in that moment, based on all the available information in a split second. Yet, ultimately, Bu’un is the final arbiter, and I believe this is a core part of the human experience.

While I captured a photo showing the men strike was off, I understand that the essence of kendo goes beyond any single match or image. The path of kendo—and all budo—is never straightforward; it’s filled with victories, defeats, trials, tribulations, and the accumulation of wisdom gained from each. That is where true victory lies.

It reminds of a well-known teaching in kendo. The phrase “Utte hansei, utarete kansha” (打って反省, 打たれて感謝) embodies a core philosophy: “Reflect when you strike; be grateful when struck.” This teaching emphasizes that true progress in kendo comes not only from victory but also from introspection and humility. When you successfully strike an opponent, the phrase encourages self-reflection, urging you to consider areas for improvement rather than simply celebrating success. Conversely, when you are struck, rather than feeling defeated, you are encouraged to feel gratitude—both for the lesson that the strike imparts and for the opportunity to identify your weaknesses. This mindset fosters continuous growth, respect for others, and a deeper understanding of oneself, reinforcing kendo’s spirit of self-improvement and mutual respect. An acceptance of Bu’un gives one the latitude to make everything a learning experience.

Takenouchi will no doubt be pleased with his victory in the final, while Goya will surely be lamenting his loss. But I guarantee that both firmly believe in and accept the universal force of Bu’un, as do all the competitors at the All-Japan Kendo Championships. And, I bet they all learn from it. That’s why they’re there.

That’s a great concept to share, bro. People need to know that. And Takenouchi knows his men was off and probably he was going to your former student. “Sorry, mate. This time the martial god smiled at me.” i.e. he has bu’un. Thank you for writing about it!!

Cheers Hiro. I’m looking for a place where they sell six-packs of Bu’un.

This was an interesting read, I hear that term thrown around quite a bit, but wasn’t quite sure exactly what it was referring to. It was used recently by Okido sensei during a practice two weeks ago, who was shushin for that match.

You sure hear it a lot Nicholas. 武運 really captures the idea of leaving things up to fate and giving your best in the moment. And of course, in the course of regular training.

Hi Alex,

I loved reading your reflections on Bu’un and the Kendo Championships. It really got me thinking about how this concept doesn’t just apply to martial arts but to life as a whole, especially when we think about what we often call “merit.” Bu’un shows us that no matter how skilled or prepared we are, there’s always that element of chance—luck, really—that influences the outcome. It’s humbling, and it reminds us of the limits of our control.

In Budo, we can see two equally skilled fighters face off, and yet the result often comes down to timing, momentum, or just a flash of luck in the moment. This makes me reflect on the idea of “merit” in society, too. Just like in Kendo, where success is partly luck, many of the achievements we see in life aren’t simply about effort or skill—they’re often shaped by factors outside of one’s control. It’s a reminder to be humble about our successes and understanding about others’ challenges.

Especially in a context in which we do not know the private life of the participants, and therefore have no idea of whom actually is more meritant, based on where he comes from.

This idea also helps me see why Budo are often called “arts of peace.” If we were actually betting our lives on these fights, we’d be wagering not only on our skill but also on luck, which is both a humbling and sobering thought. And this takes me further still—it makes me wonder how many swordsmen in history, who may have been better than the legends like Yagyu or Musashi, might have simply had worse luck. They may have been equally talented or even more skilled, but luck wasn’t on their side. This perspective even changes how I think about these famous figures, showing how much chance may play a role in who becomes legendary and who is forgotten.

Maybe it’s this balance of skill and chance that makes Budo truly about humility and self-growth. Bu’un teaches us that our practice isn’t really about winning or losing, but about acceptance and resilience. It’s a reminder to prepare as best we can, while knowing that there will always be things beyond our control. A though we must have for our own, but also for the people we face, in a Dojo or in life.

Hope we can chat more about this one day!

Best,

Jordy

Hey Jordy mate,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts—I’m glad my reflections on Bu’un resonated with you. You’re right: it’s humbling to realize how much of life, like Budo, depends on factors beyond skill alone. Bu’un reminds us that, just like in a match, effort and merit only go so far, and then luck takes over. It makes me think about success and failure differently, both for ourselves and the people around us.

Your point about the unsung swordsmen who may have been just as skilled as Musashi but had worse luck really hits home. It’s a reminder that legends aren’t just made by talent alone; they’re shaped by fortune too. And books and movies made about them 400 years after they die 🙂

Thanks again for the perspective! Let’s definitely chat more about this sometime.

Best,

Alex

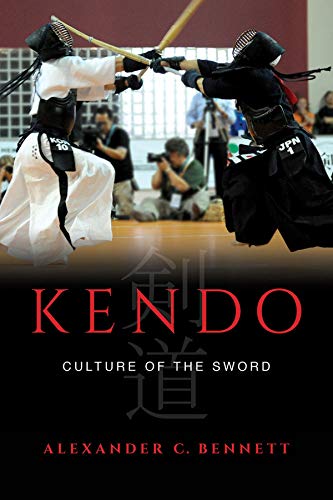

Bennett Sensei, thank you for writing this great article. I also read your book on kendo and really enjoyed it.

It’s fun to know that this phenomenon has a name in Japanese. Growing up doing kendo, my Sensei would say something like, “Don’t let them get the close one. If you do and it’s called, it’s your fault.”

Hi Chris,

thanks for your comment. I’m glad you liked my book! I reckon it’s your fault everytime you get hit… Not many blameless days!

Hi Alex, Thanks for the article and also mentioning the BKA seminar! When I watched in real time I thought it was ippon I thought Takenouchi moved in with true intent was this similar to Miyazaki’s men when he defeated Eiga San?