Budo Beat 49: Jazz, Jamming, and Jigeiko

The “Budo Beat” Blog features a collection of short reflections, musings, and anecdotes on a wide range of budo topics by Professor Alex Bennett, a seasoned budo scholar and practitioner. Dive into digestible and diverse discussions on all things budo—from the philosophy and history to the practice and culture that shape the martial Way.

I went to a jazz jam session in Kyoto on Sunday night. I know absolutely nothing about music. I certainly can’t read it, cannot talk about it intelligently, and would seriously struggle to name what key anything is in. I went along as a complete outsider to chill out to some easy listening. Instead, I was quite blown away.

A quick confession before going any further. I know a few musical budoka, and much of what follows will be blindingly obvious to anyone who actually belongs in that world. These are my amateur impressions, nothing more.

When I was thirteen, in my first year of high school, music was compulsory. Like many boys of that age, we mostly took the piss. We were made to sit a music aptitude test, and a few days later my teacher, Mr Cookson, pulled me aside. He told me I seemed to have some musical potential and asked whether I might be interested in taking up an instrument in the school orchestra.

My response was immediate and regrettably idiotic. No thanks! Music was for girls. Eww. If I could go back in time and meet my thirteen-year-old self, I would give me a bloody good kick up the arse. It remains one of my genuine life regrets. Sorry, Mr Cookson. I was a total dickhead.

I sometimes wonder how competent I might be with a guitar, or any instrument at all, if I’d devoted even a fraction of the time I later poured into budo. As it stands now, I suppose I do play a mean air guitar…

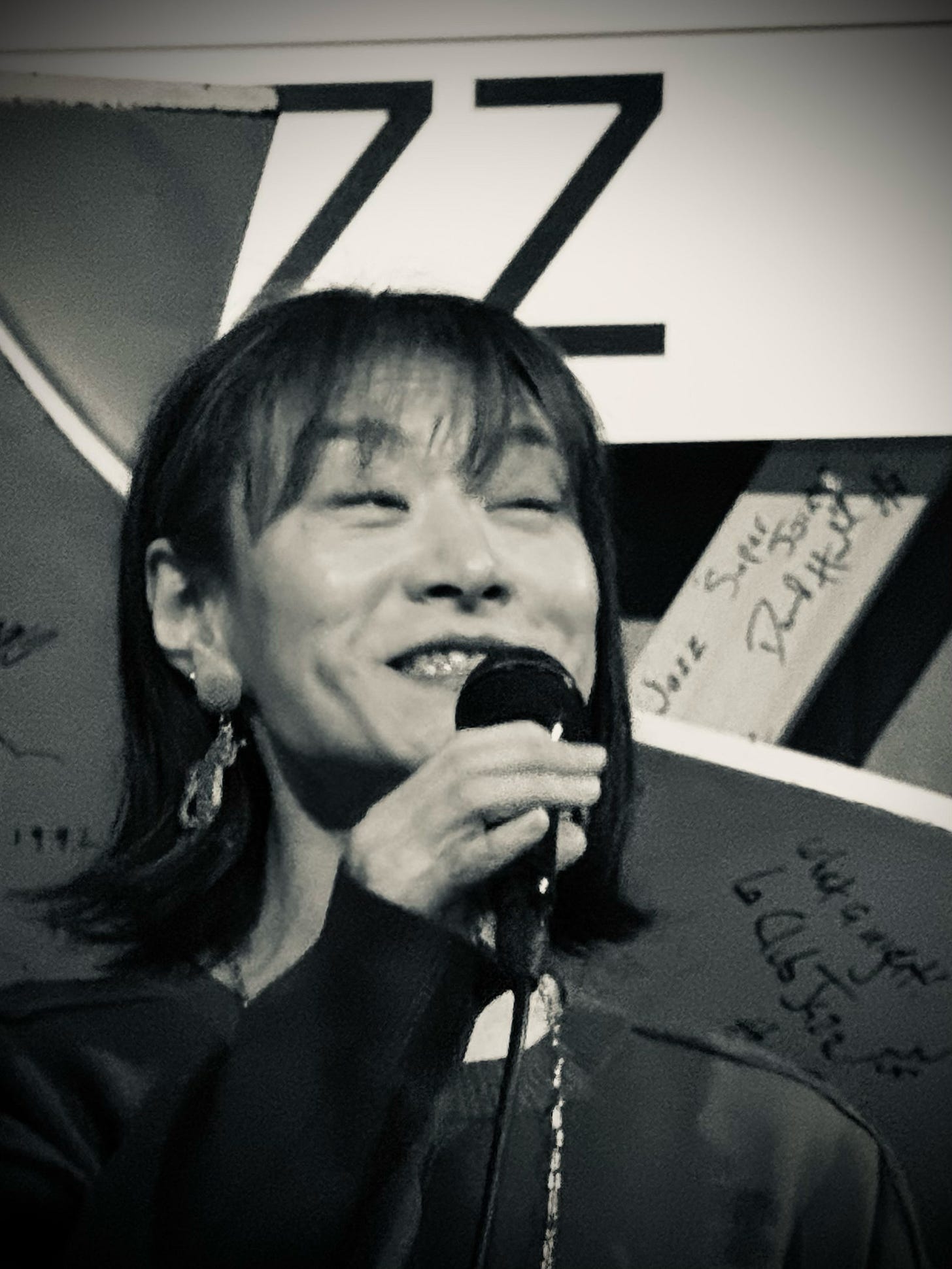

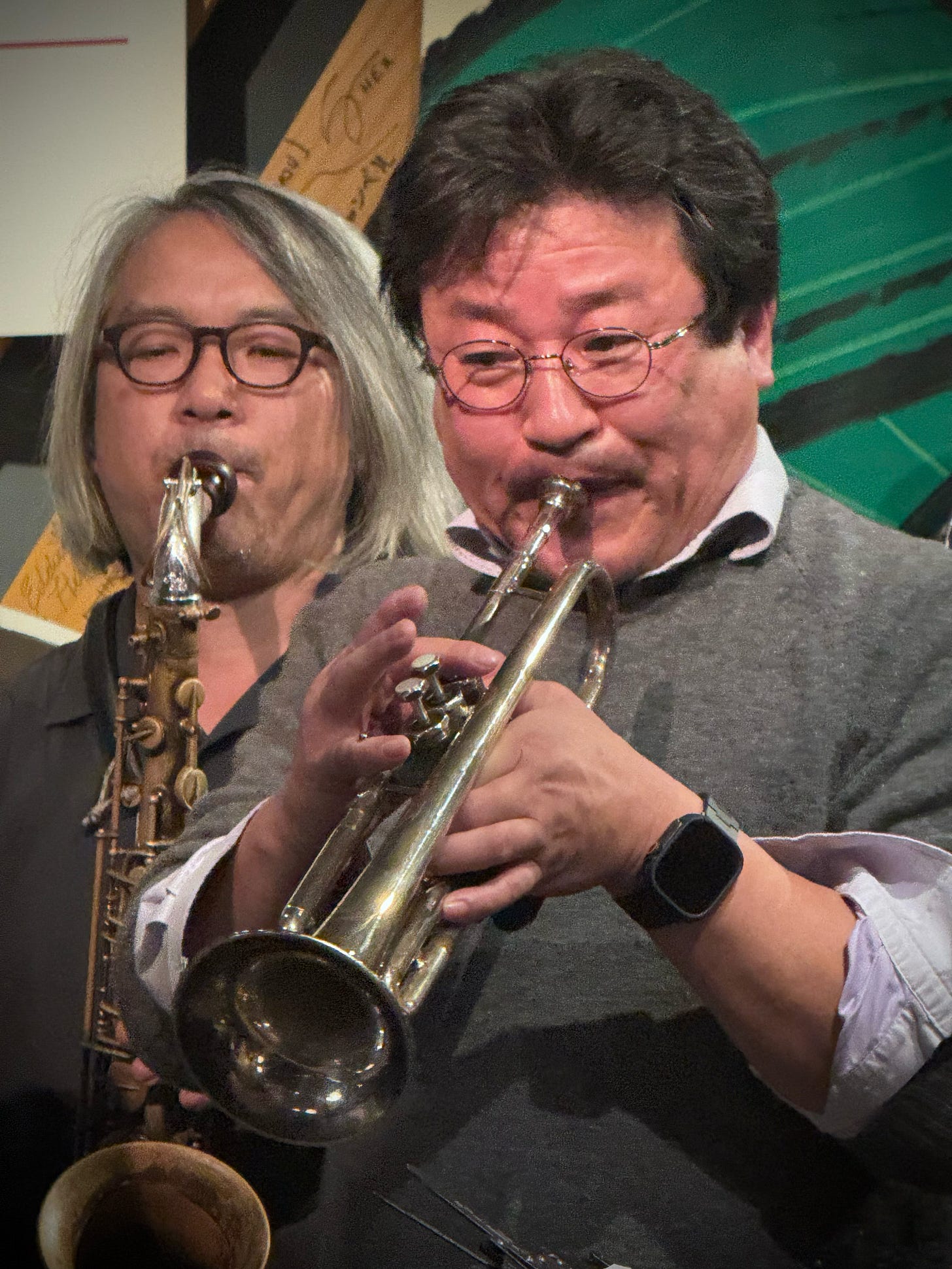

Anyway, the club itself was a small jazz place in Kyoto called Le Club Jazz. With that name, there’s little chance of walking in there by accident!

I trundled in with my kendo friend Karen and we were immediately asked what instruments we played. It was jam night after all. When we said none, the next assumption came quickly enough. Perhaps we were singers. I assured them I would NOT do that to anyone present. And so, it soon became clear that we were the only non-musos in the room. I felt a bit like one of those tourists I see wandering into the Kyoto Butokuden on a Wednesday night, watching a kendo session with no prior knowledge and no idea what on earth is going on.

It was not just the technical skill of the 20-or-so random musos there, though there was oodles and oodles of that. It was the atmosphere that intrigued me. A large group of individuals who clearly knew what they were doing, stepping into something unscripted, listening intensely, taking turns, taking risks, sometimes overshooting, sometimes landing something that lifted the whole room. There was no rehearsal, no safety net, and no visible conductor, only a room bound together by a shared passion. I was utterly enthralled. Before I knew it, four hours had passed.

About halfway through, it dawned on me that I had seen this before. Many times. On a dojo floor. What I was watching was good old jigeiko (free sparring).

There is a moment in jigeiko that’s hard to pin down in words. It doesn’t appear in handbooks or grading criteria, and sensei rarely spell it out. It’s when technique stops feeling deliberate. You move before conscious intention catches up. You strike without narrating it to yourself. You get hit, register it, adjust, and continue. At some point, the exchange begins to run on its own.

That is exactly what I saw in that jazz club.

Someone would begin, tentatively or boldly. Others would support, take the baton, leave space, or gently pull things back when they drifted. Occasionally someone pushed too hard and the balance seemed to wobble. Then, someone else would anchor it again and there would be grins all round. It was messy, serious, generous, testing, forgiving, and very alive. All at once! Just, wow! (See a video at the bottom of this post.)

This is precisely why free sparring in kendo and other budo is so important. Kata are like sheet music. Kihon and drills are scales. Shiai, a formal match where points are contested and mistakes are punished, is the concert performance where precision matters and errors are costly. Jigeiko, however, is the jam session. It’s where you find out how much you actually understand what you’ve been practising.

In jigeiko, you do not simply impose your will. You watch and listen. You read the distance, the timing, the temperament of the person in front of you. You adjust your rhythm, your pressure, your breathing, your waza… You offer something and see what comes back.

A good jazz jam, from what I could see, works in kind of the same way.

Despite appearances, it is not a free-for-all. There are rules, but they are largely invisible. You listen before you play. There’s a bit of eye contact going on there. You don’t trample others to show off. You take risks, but you own them. If you throw the rhythm off, you fix it or you follow the person who does. Everyone understands this without needing to say it. Although I was completely oblivious to any mistakes that were made, I could tell when something was off because of the wry smiles of the performers. Almost like “mairimashita”.

Based on what I saw, I suspect bad jigeiko and bad jam sessions fail for the same reason. Ego. The person who treats every exchange as a personal audition poisons the space. In jazz, it sounds like overplaying, drowning out others, refusing to leave space. In kendo, it looks like constant charging in, obsessive point-hunting, or forcing a favourite technique regardless of context. In both cases, the exchange stops gelling.

Everything is aligned, not because it’s planned, but because everyone involved is paying attention and respecting each other.

One of the most striking things about the jam session was how serious it was without becoming stiff. There was a hierarchy for sure, but it remained fluid. Less skilled players were not crushed, and exposed mistakes were not punished. The atmosphere was supportive rather than indulgent. Anyone who has experienced jigeiko knows that feeling.

There is also a shared humility. You can walk in feeling sharp and be taken apart, almost casually, by someone who hardly seems to move. Watching the jazz players, I recognised that same moment: when what you thought was working suddenly isn’t, and you’re left adjusting on the fly. It’s not particulaly dramatic, just quietly clarifying. And it really looked as though they were having the time of their lives doing it.

That experience changes what you value over time. Among older practitioners in kendo, the obsession with winning often fades and the pleasure of dialogue emerges. Jazz, of course, is not a competitive pursuit in the first place, and I may be completely wrong here. But watching that room, I wondered whether many of the players had come through more formal or “competitive” musical backgrounds, and whether jazz offered them a different kind of freedom. From the outside, it felt as though the need to impress had given way to the desire to connect.

Perhaps that is why walking into that jazz club knowing nothing felt so powerful. I wasn’t trying to decode it or measure it. I was just watching people deal with each other in real time, with no script to hide behind. It always worked, but you could feel when it loosened, tightened, or briefly lost its shape, and that just added to the thrill.

With the jigeiko jam, most of the time it’s scrappy and inconclusive; now and then it comes together. And when it does, you don’t need to explain it. You just bow, step back, and know you were fully there for a moment. That’s why we love it. “You’ve got to dig it to dig it. You dig?” — Thelonious Monk

No comments yet.